Description Cards - Macomb ISD Science Education Support Site

advertisement

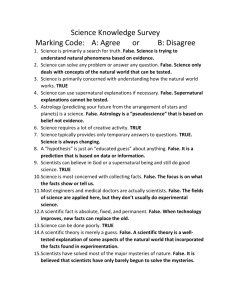

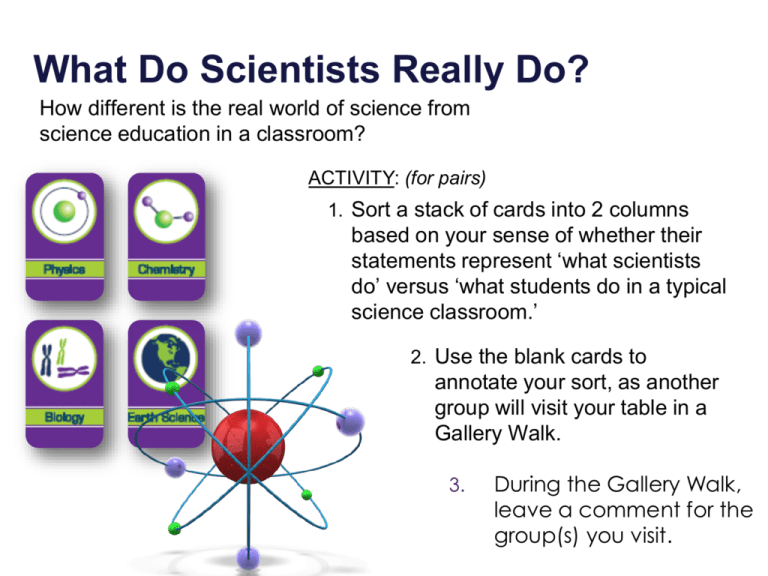

What Do Scientists Really Do? How different is the real world of science from science education in a classroom? ACTIVITY: (for pairs) 1. Sort a stack of cards into 2 columns based on your sense of whether their statements represent ‘what scientists do’ versus ‘what students do in a typical science classroom.’ 2. Use the blank cards to annotate your sort, as another group will visit your table in a Gallery Walk. 3. During the Gallery Walk, leave a comment for the group(s) you visit. SCIENTISTS SCIENCE STUDENTS They identify questions that lead to scientific explanations of natural phenomena. They consume the facts, and the ideas of science without a thorough exploration of the evidence that supports it. Rather than strictly follow a prescribed ‘scientific method,’ a wide array of methods are developed and used to pursue questions. They use a universally accepted scientific method to define the process for pursuing questions. In essence, they perceive science as a powerful way of thinking which provides them thrilling opportunities to engaging in fascinating questions and puzzles. In essence, they perceive science as a huge body of complicated knowledge. They rely heavily on an understanding of standards of evidence and rules of logic. They rely heavily on their ability to remember facts and terminology as they strive to comprehend or deduce the accepted correct answers to scientific questions. They use a range of techniques to collect data systematically and a variety of tools to enhance their observations, measurements, data analyses and representations. They participate in experiments that always involve directly observable, controlled and independent variables. They present results mainly in tables, line graphs and bar graphs. They frequently talk and collaborate with their colleagues, both formally and informally. They exchange emails, engage in discussions at conferences, and present and respond to ideas via publications in journals and books. Their discussions with colleagues center on understanding set logistics and procedures and on the acceptable answers to questions given to them. They typically share credit for results because they depend on one another for ideas, perspectives and productivity. They are independently accountable for comprehending ideas and production of reports. They hold data and evidence in a primary position in deciding any issue. They receive explanations from authorities such as books and experts. They modify or abandon accepted explanations when new, well-founded data conflict with a hypothesis or theory. When experimental results don’t support an accepted explanation, they assume there was an error in the experiment.