voting participation - Professional Learning Library

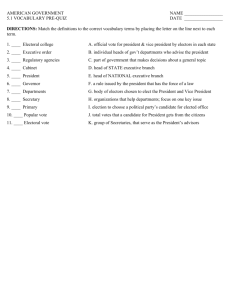

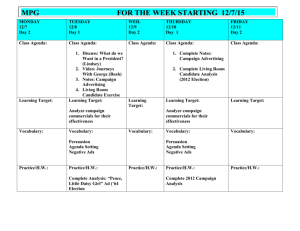

advertisement