The Electoral College

advertisement

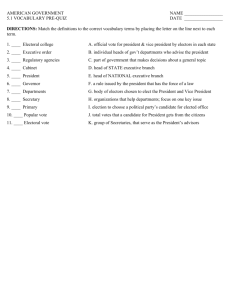

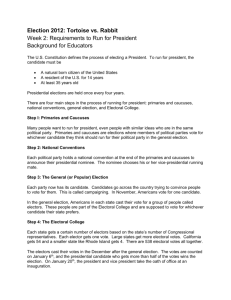

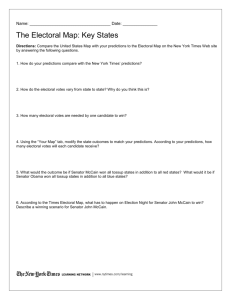

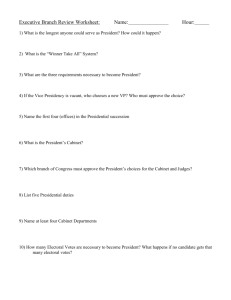

The Electoral College pols100/U.S. Government The Electoral College After the two parties have held their conventions and nominated their candidates, the real campaign begins. For about three months, the candidates spend all their time making their case to the American people. This involves a lot of travel, and a lot of time “on the stump,” which is to say giving speeches at different locations. The candidates must make decisions daily, and toward the end by the hour, about which states to visit and where to invest their advertising dollars. To understand how a campaign strategy is developed and how it guides these decisions, you first have to understand the Electoral College. The Origin of the Electoral College The Electoral College is the institution that officially elects the President of the United States. In 1787, when the Constitution was written, communications between different parts of the country was very slow. The Founding Fathers were worried that no one man or group of men would be sufficiently well known throughout the country to win a popular election for president. It was decided instead that the people would elect a body called the Electoral College, and that body of persons would choose the President. The Founders imagined that candidates would run openly for the office of elector, and that the voters would choose among the candidates as they would candidates for the House or Senate. Whom do you trust to choose a President for you? But in fact it has never worked like that. Everyone knew that the first president was going to be George Washington, and so no one paid any attention to who the electors were. Very quickly after that the American political party system began to form. Ever since, each party has run “slates” of electors for its preferred candidate. Electoral College Math Here is how the Electoral College works: Each state receives a number of electoral votes equal to the number of its seats in the House of Representatives plus the number of its seats in the Senate. Since every state has exactly two Senate seats, just add two to the number of House seats. In addition to the fifty states, Washington D.C., a federal territory, gets 3. So: Arkansas California South Dakota House Seats 4 55 1 Senate Seats 2 2 2 Electoral Votes 6 57 3 To calculate the total for the Electoral College, you need to add the following: U.S. House of Representatives U.S. Senate Washington D.C. Total: The minimum needed to win: 435 100 3 538 270 Under the rules of the Constitution, a candidate must win a majority in the Electoral College to be elected President. Half of 538 is 269, so a candidate must win 270 electoral votes or more. In the event that no candidate manages to win a majority, the election will be decided by the U.S. House of Representatives. This has happened once, very early. Here is a graph illustrating the Electoral College outcome in the 2004 election. Each square represents one electoral vote. Red squares are votes won by the Republican candidate, Bush. Blue squares represent votes won by the Democrat, John Kerry. How Electoral Votes are Distributed after an Election Each state can devise its own system for distributing the electoral vote. In the first few elections, many states let allowed the state legislature to decide with no popular election at all. Today every state and Washington D.C. will hold an election. In most states the system in place is the called “Unit Rule,” or more commonly, winner take all. Each candidate runs a slate of electors in a state equal to the number of that state’s electoral vote. The slate is a list of persons pledged to vote for that candidate. So John McCain’s slate in Arkansas will have six people who are pledged to vote for him if he wins that state. Barack Obama will have his own six pledged to vote for him. Likewise, South Dakota will have a slate of three electors representing John McCain, and another slate of three representing Barack Obama. There will be additional slates for third party candidates. Who will these electors be? Party officials or prominent supporters of the candidate, for the most part. When voters go to the polls, they will not see the names of these electors. They will see only the various tickets: McCain/Palin; Obama/Biden; etc. Once the popular vote has been counted, meaning the actual votes cast, whichever ticket wins a plurality gets all three of South Dakota’s electoral votes. Another way to put this is that the slate pledged to vote for the candidate who won the popular vote in that state is elected to the Electoral College. You can see the outcome in New Mexico in the image on the right. In 2008, John McCain/Sarah Palin won 203, 054 votes, just over 53% of the popular vote. Barack Obama/Joe Biden received 170.924, almost 45%. The Constitution Party came in third with fewer than 2000 votes. You can see above a list of the electors pledged to vote for each candidate. Since McCain/Palin won more popular votes than any other ticket, all three of McCain’s electors were elected to the Electoral College. Here are their names: Dennis M. Daugaard (Lt. Governor) Larry Long (Attorney General) Mike Rounds (Governor) Obama/Biden also had three electors: Gary Job Catherine V. Piersol Jack Billion None of these made the Electoral College In North Carolina, Obama/Biden beat McCain/Palin by about three tenths of one percent of the popular vote a won only a plurality of the vote statewide. But the Obama ticket got all 15 of that state’s electoral votes. That is “winner take all.” Electoral College Outcomes vs. the Popular Vote Electoral College results, largely because of the winner take all rule in almost all states, will differ significantly from the popular vote totals. Consider 1992 D R I 1992 Popular Vote Bill Clinton/Al Gore George Bush/Dan Quayle Ross Perot/James Stockdale Percentage Percentage 44,909,806 43.01% Electoral Vote 370 39,104,550 37.45% 168 31.2% 19,743,821 18.91% 0 0% 68.8% So Democrat Bill Clinton won only 43% of the popular vote. George Bush (George W.’s dad), won 37%. In that election, a third party candidate, Ross Perot, won nearly 20% of the popular vote. But Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton won 370 electoral votes, for a strong majority in the Electoral College. And so Bill Clinton became our 42nd President. The same thing happens again in 1996. D R I 1996 Popular Vote Percentage Percentage 49.23% Electoral Vote 379 Bill Clinton/Al Gore Bob Dole/ Ross Perot/Pat Choate 47,400,125 39,198,755 8,085,402 40.72% 8.40% 159 0 29.6% 0.0% 70.4% Ross Perot’s support goes way down in 96, but it’s still eight million people, and that’s enough to keep Bill Clinton from achieving a majority of popular support. Both in 1992 and 1996, more people voted against Clinton than voted for him. Is there anything wrong with that? It is not easy to see what. It is very likely that the presence of Ross Perot in the race in 1992 cost George Bush (41) the election. There is no way to prove that, but it seems likely that most of the 20 million people who voted for him would have voted for Bush rather than Clinton. Third party candidates cannot win presidential elections, but they can sometimes decide them in favor of one party or the other. Losing the Popular Vote but Winning the Election The Electoral College makes it possible for a candidate to lose a plurality of the popular vote and still win the election. Although this is very rare, it happened in 2000. 2000 Popular Vote Percentage Percentage 47.87% Electoral Vote 271 George W. Bush/Dick Cheney Al Gore/Joe Lieberman Ralph Nader/Winona La Duke 50,460,110 51,003,926 48.38% 266 49.4% 2,883,105 2.73% 0 0.0% 50.4% Al Gore won 48.38% of the popular vote in that year, with George W. Bush winning 47.87%. That’s a difference of less than one percent, but it still means that more people voted for Gore than for Bush. But Bush put won just the right collection of states to give him a very narrow victory in the Electoral College: 271 to Gore’s 266. That’s how George W. made it to the White House. Is that unfair? No. The rules are the rules. If you don’t like ‘em, work to get ‘em changed. One thing about the 2000 election that was unprecedented is that the outcome was not known for months. The two candidates were separated by a razor thin margin in Florida. It took a series of decisions in the Florida State Supreme Court and the United States Supreme Court to decide how the votes there would be counted. Here is the official outcome. 2000 Florida Results George W. Bush/Dick Cheney Al Gore/Joe Lieberman Ralph Nader/Winona La Duke Popular Vote Percentage 2,912,790 48.85% Electoral Vote 25 2,912,253 48.84% 0 97,488 1.63% 0 Would you just look at that! Out of nearly six million votes cast, George W. Bush wins the popular vote in Florida by 537. A flu bug in the Florida panhandle would have made Gore President. Don’t ever let anyone tell you that your vote doesn’t matter. Consider also South Dakota. Here is our vote in the same election. 2000 South Dakota Results George W. Bush/Dick Cheney Al Gore/Joe Lieberman Popular Vote Percentage 190,700 60.30% Electoral Vote 3 118,804 37.56% 0 Bush wins by a comfortable margin in South Dakota. But how comfortable was it? Bush won by two electoral votes. South Dakota cast three electoral votes. If 15% of South Dakota voters had gone the other way, Gore would have gone to the White House rather than Bush. Both Florida and South Dakota illustrate something vital about the Electoral College: it makes states very important.