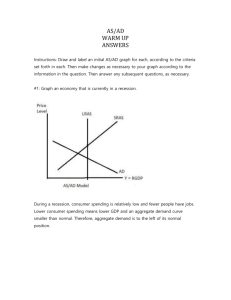

Aggregate Demand and Supply

advertisement

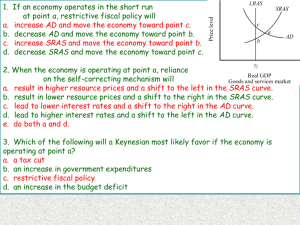

Aggregate Demand and Supply Linking Monetary Policy to Price and Output Aggregate Demand • Define aggregate demand as the total demand for an economy’s output (production of goods and services) over a given period of time. • Demand may come from households (consumption), firms (investment), the public sector (government spending) or foreign households, firms, or governments (net exports). – YAD = C + I + G + NX • We assume an inverse relationship between price and aggregate demand Aggregate Demand Rises as Price Falls • Suppose aggregate prices in the economy fell • This would cause the demand for money to shift in, causing interest rates to decline – Alternatively, the real money supply (M/P) rises, causing interest rates to fall. • With lower interest rates, the opportunity cost of consumption is lower: – P↓ Md↓ i↓ C↑ • With lower interest rates, the direct cost of investment falls: – P↓ Md↓ i↓ I↑ • With lower interest rates a country’s currency will depreciate. A weaker currency makes exports cheaper and imports more expensive – P↓ Md↓ i↓ Exchange Rate↓ NX↑ The Aggregate Demand Curve P 2 1 AD 100 180 Y Factors that Shift the AD Curve • Anything (other than price!) that causes C, I, G, or NX to increase will shift the AD curve to the right. • C increases when… – There is an increase in consumer confidence, leading to more current consumption and less current savings – Taxes are cut leaving consumers with more income to spend (assuming Ricardian Equivalence doesn’t hold!) • I increases when… – Business confidence rises, prompting firms to invest more for the future. • G increases when… – Government spending increases • NX increases when… – There is increased preference for domestically produced goods. • An increase in the money supply will cause AD to shift right – Interest rates are lower, so C and I rise. The currency weakens, so NX increases. Increasing the Money Supply P 2 1 AD2 80 140 AD1 200 Y Long Run Aggregate Supply • In the long run, money is neutral – Any changes in the money supply will be met by a proportionate change in prices – Increasing the money supply will not affect the economy’s output in the long run. • Long run output is determined entirely by an economy’s productive capacity – Production Function: YP = A*F(K,L,H,N) • Only changes in real variables can affect potential output. – Price does not have any effect on YP • In the long run, all resources are being efficiently utilized such that unemployment equals the natural rate Long Run Aggregate Supply LRAS P 2 1 YP = 140 Y Short Run Aggregate Supply • In the short run, money is not neutral – An increase in the money supply need not trigger an immediate increase in price. – Prices are sticky due to uncertainty, menu costs, and long-term contracts. • Suppose output prices across the economy rise. – Wage and input contracts do not immediately adjust to higher output prices. – Profit per unit rise, leading to an increase in production. – Eventually, these contracts will readjust to factor in the higher cost of living, erasing the increased profits and returning output back to YP Short Run Supply Shocks • Tightness in the labor market. – Suppose that because of a big economic expansion, the economy is producing at an output level Y that is greater than YP. – This suggests that the economy is using more labor than it normally does. – To get people to work longer hours, you have to pay them more. – This increase in labor costs will shift the SRAS curve left, as profit per output falls when labor costs rise. • Expectations about inflation – If workers expect inflation to be higher in the future, they will demand higher wages in anticipation of this increase in the cost of living. – Higher wages reduce firm profit and shift SRAS left • Supply shocks to critical raw materials – Suppose a war broke out between the US and Iran. Oil prices would rise dramatically – Since oil is such a pervasive part of nearly everything we produce, production costs would rise significantly. – The SRAS curve would shift left as the return on production fell. Lower Expected Inflation LRAS1 SRAS1 P SRAS2 1 YP = 140 200 Y Short Run Equilibrium P SRAS PH Surplus P* Shortage PL AD Y* Y Long Run Equilibrium LRAS P SRAS2 SRAS1 P* PL AD YP Y Over-employment Wages must rise! Y The Self-Correcting Economy • Suppose that a decrease in consumer confidence causes the aggregate demand curve to shift left. • At current prices, there will be a surplus of production as consumers demand fewer goods and services • Firms will cut both their prices and their production until the surplus inventory is sold. • Output and prices fall in the short run, resulting in a recession. • Eventually, lower output prices and less demand for labor will induce a fall in production costs. • The SRAS curve will shift right until full employment output is restored at a lower price (assuming consumer confidence never recovered). • The economy will always return to full-employment output, but how long does this adjustment process take? A Drop in Consumer Confidence LRAS P SRAS1 SRAS2 P1 P2 P3 AD2 Y YP Unemployment Wages must fall! AD1 Y Keynesians vs. Monetarists • If you believe that prices and wages are very slow to adjust, then would you advocate an active or passive role for economic policy? • In the last example, the economy suffered a recession as a result of the drop in consumer confidence. – The duration of the recession was entirely dependant on the amount of time it took for price and wage contracts to readjust and shift the SRAS curve out to the right. – If this happened quickly, then the recession was brief. • What if in response to the drop in consumer confidence, the Fed decided to buy bonds from the public? – This would expand the monetary base, and assuming no significant drops in the money multiplier, an increase in the money supply. – In the short run (at least) this will cause interest rates to fall and shift AD out to the right. – By compensating for the drop in consumer confidence with easy liquidity, the Fed can hasten the end of the recession, albeit at the cost of higher prices. Central Bank Intervention LRAS P SRAS1 P1 P2 P3 AD2 Y YP AD1 = AD3 Y Conclusions • Shift in aggregate demand affects output only in the short run and has no effect in the long run • Shifts in aggregate demand affects only price level in the long run • Shift in short run aggregate supply affects output and price only in the short run and has no effect in the long run • The economy has a self-correcting mechanism • The pace of self-correction may justify policy intervention. Vietnam War Buildup LRAS P SRAS2 SRAS1 P3 P2 P1 AD2 AD1 YP Y Y OPEC Oil Shocks LRAS P SRAS2 SRAS1 P2 P1 AD1 Y YP Y The 1990’s Tech Boom LRAS P SRAS1 SRAS2 P1 P2 AD1 YP Y Y The Current Situation LRAS SRAS2 P SRAS1 Rising oil prices raise production costs P2 P1 Housing market crash lowers consumer confidence AD2 Y YP AD1 Y