Arguments in Philosophy

advertisement

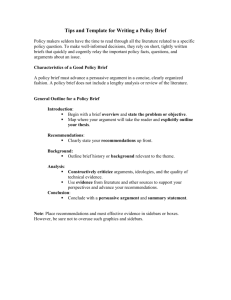

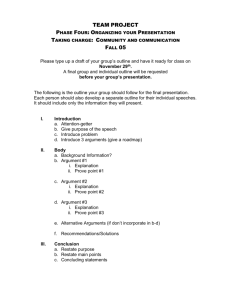

Arguments in Philosophy Introduction to Philosophy 1 Arguments Philosophy is the art of constructing and evaluating arguments It’s all about the argument Arguments are meant to be convincing So philosophers must be sensitive to what makes an argument convincing Or not 2 Thinking Critically First step: Think Critically What is the argument trying to say? Why does the argument succeed, or not? The form of the argument What’s good, bad, or indifferent? What’s the point? How do we get to the point? Structure How do the parts of the argument fit together? 3 General Structure In general, arguments consist of: The thesis or position argued for The reasons why the conclusion should be accepted The conclusion The premises Usually this is written in “standard form”: Premise 1 (Justification) Premise 2 (Justification) Therefore, Conclusion (Justification) 4 Two kinds of argument In general, there are two kinds of argument: Deductive Arguments Inductive Arguments These arguments work (slightly) differently, so they’re evaluated differently 5 But let’s be more specific… A statement is any unambiguous declarative sentence about a fact (or non-fact) about the world. It says that something is (or isn’t) the case. An argument is a series of statements meant to establish a claim. A claim or conclusion is the statement whose truth an argument is meant to establish. A statement’s truth value is either true or false. All statements have a truth value. A statement is false when what it says about the world is not actually the case. A statement is true when what it says about the world is actually the case. A premise is a statement that is used in an argument to establish a conclusion. 6 Deductive Arguments A deductive argument is: VALID if its premises necessarily lead to its conclusion. That is, if you were to accept that the premises are all true, you must accept that the conclusion is true. SOUND if it is valid and you accept that all its premises are true. A good, convincing argument is sound. A bad argument is any other kind of argument. VALIDITY + TRUE PREMISES* = SOUND *or, at least, accepted premises 7 Examples All people are mortal. Socrates is a person. Therefore, Socrates is mortal. All people are mortal. My dog is mortal. Therefore, my dog is a person. Invalid. Oranges are green. All green things make me sick. Therefore, oranges make me sick. Sound Valid. Not sound. Whales know how to play hockey. Therefore, Canadians like winter. Invalid. 8 Notice… Validity does not depend on the truth of the premises. All people are mortal. My dog is mortal. Therefore, my dog is a person. The premises are true. But the argument is still invalid. Soundness does not depend on the truth of the conclusion. An argument can be bad even if the conclusion is obviously true. 9 Evaluating Deductive Arguments Good arguments must be sound. If you want to accept of an argument, you would have to show both validity and soundness Bad arguments can be bad in two ways: Invalid You can show that the conclusion does not follow from the premises Unsound You can show that at least one premise is unacceptable 10 Inductive Arguments Inductive arguments are not truth preserving Even in a good inductive argument where the premises are true, the conclusion does not have to be true. At most, the conclusion is most likely true. Inductive arguments are meant to make conclusions more likely or more acceptable. 11 Inductive Arguments An inductive argument is: STRONG if its premises make the conclusion probable That is, if you were to accept the premises as true, then you would have to accept that the conclusion was probably true COGENT if it is strong and its premises are accepted A good, convincing argument is cogent. STRENGTH + TRUE PREMISES* = COGENT 12 Examples This cooler contains 30 cans. 25 cans selected at random contained soda. Therefore, all the cans probably contain soda. This cooler contains 30 cans. 3 cans selected at random contained soda. Therefore, all the cans probably contain soda. Cogent Weak Every monkey I’ve seen (over 500) has blue teeth. Therefore, the next monkey I see will probably have blue teeth. Strong, but not cogent 13 Notice… Strength admits of degrees. An argument can be stronger or weaker Usually, the more evidence available, the stronger the argument Strength does not depend on the truth of the premises 14 Evaluating Inductive Arguments Good arguments must be cogent. If you want to accept of an argument, you would have to show both strength and cogency Bad arguments can be bad in two ways: Weak You can show that the premises does not make the conclusion more probable Not cogent You can show that at least one premise is unacceptable 15 Argument by Analogy One particular kind of inductive argument is an Argument by Analogy Comparison of two or more things Concludes that they share characteristic(s) Example: Because they share other characteristic(s) Watches exhibit order, function, and design. They were also created by a creator. The universe exhibits order, function, and design. Therefore, the universe probably was created by a creator. Evaluated like other inductive arguments 16 In Practice… Identify the conclusion Identify the premises What is the claim? How is the claim supported? Often, we first have to get rid of anything unnecessary – mere rhetorical flourishes, repetitions, and irrelevancies. Reformulate the argument Try to put it into standard form Often, we’ll have to add premises that are implied but not stated. 17 In Practice… Identify the form of the argument How are the premises supposed to lead to the conclusion? Deductive? Inductive? Assumptions? Subarguments? (This will help us add/delete premises) Evaluate the argument Valid? Sound? Strong? Cogent? WHY? 18 Example For Death is to be as it were nothing, and to be deprived of all sensation... And if no sensation remains, then death is like a dreamless sleep. In this case, death will be a blessing. For, if any one compares such a night as this, in which he so profoundly sleeps as not even to see a dream, with the other nights and days of his life, and should declare how many he had passed better and more pleasantly than this night, I think that not only a private man, but even the great king himself, would find so small a number that they might be easily counted. 19 Example For Death is to be deprived of all sensation... if no sensation remains, then death is like a dreamless sleep. ...death will be a blessing. ...if any one compares such a night [of sleep without dreams]... with the other nights and days of his life, and should declare how many he had passed better and more pleasantly than this night, I think.. [he] would find so small a number... 20 Example Death is to be deprived of all sensation. If no sensation remains, death is like a dreamless sleep. Anyone will consider a dreamless sleep better than most days and nights. --Death is a blessing. 21 Example Death is to be deprived of all sensation. If no sensation remains, death is like a dreamless sleep. Death is like a dreamless sleep. Anyone will consider a dreamless sleep better than most days and nights. Anyone will consider death better than most days and nights. Anything that is better than most days and nights is a blessing. --Death is a blessing. 22 Example Death is to be deprived of all sensation. (Assumption) If no sensation remains, death is like a dreamless sleep. (Assumption) Death is like a dreamless sleep. (Conclusion from 1 and 2) Anyone will consider a dreamless sleep better than most days and nights. (Assumption) Anyone will consider death better than most days and nights. (Conclusion from 3 and 4) Anything that is better than most days and nights is a blessing. (Assumption) --Death is a blessing. (From 3, 5, and 6) 23