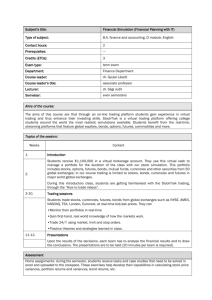

Stock Index Futures

advertisement

Chapter 8 Stock Index Futures • Organization of Slides: – – – – History Futures Contract Specifications Risk Management Index Calculations (Appear in the Extra Section). ©David Dubofsky and 8-1 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Stock Index Futures, History I. • Trading began on February 24, 1982, when the Kansas City Board of Trade introduced futures on the Value Line Index. • About two months later, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange introduced futures contracts on the S&P 500 index. • By 1986, the S&P 500 futures contract had become the second most actively traded futures contract in the world, with over 19.5 million contracts traded in that year. • In May 1982, the NYSE Composite Index futures contract began trading on the New York Futures Exchange, the NYFE. ©David Dubofsky and 8-2 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Stock Index Futures, History II. • In July 1984, the Chicago Board of Trade began trading futures contracts on the Major Market Index (MMI). – Dow Jones and Company went to court to block its attempts to trade futures on the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) • But, in June 1997, Dow Jones and Company agreed to allow DJIA options, futures, and options on futures to begin trading. • On October 6, 1997, futures on the DJIA began trading on the Chicago Board of Trade. ©David Dubofsky and 8-3 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. In their short trading history, stock index futures contracts have had a great impact. • Trading in stock index futures has allegedly made the world's stock markets more volatile than ever before. • Critics claim that individual investors have been driven out of the equity markets because institutional traders' actions in both the spot and futures markets cause stock values to gyrate with no links to their fundamental values. • Many political figures have called for greater regulation, going so far as to favor an outright ban on stock index futures trading. • Fortunately, such extreme measures have been avoided. ©David Dubofsky and 8-4 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Stock index futures have become irreplaceable in the modern world of institutional money management. • Stock Index futures have revolutionized the art and science of equity portfolio management as practiced by: – – – – – mutual funds pension plans endowments insurance company other money managers. ©David Dubofsky and 8-5 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. 2 Important Details • A futures contract on a stock market index represents the right and obligation to buy or to sell a portfolio of stocks characterized by the index. • Stock index futures are cash settled. – That is, there is no delivery of the underlying stocks. – The contracts are marked to market daily. – On the last trading day, the futures price is set equal to the spot index level and there is a final mark to market cash flow. ©David Dubofsky and 8-6 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. What is an Index? • An index is, in one sense, just a number that is computed in order to measure the value of a portfolio of stocks. – Other indices have been constructed to track the values of other types of securities, such as bonds and futures. – Still other indices track such economic indicators as the consumer price index (CPI) or the index of leading indicators. • When constructing a stock market index, three issues are of particular interest: – which stocks are in the index – how each stock is weighted – how the average is computed • We will describe three different stock market indices. ©David Dubofsky and 8-7 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. A Famous Price-Weighted Index: The Dow Jones Industrial Average • When one asks: "How is the market doing?", it is usually implicit that the question is refers to the DJIA. • Other stock market indices that are computed in the same way as the DJIA, and which have futures and options trading on them include the Nikkei 225 stock index of Japanese stocks. ©David Dubofsky and 8-8 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. As of December 2001, the 30 stocks in the DJIA were: Alcoa American Express AT&T Boeing Caterpillar Citigroup Coca Cola Disney DuPont Eastman Kodak Exxon Mobil General Electric General Motors Hewlett Packard Home Depot Honeywell IBM Intel International Paper Johnson & Johnson McDonalds Merck Microsoft 3-M J.P. Morgan Chase Philip Morris Procter & Gamble SBC Communications United Technologies Wal-Mart ©David Dubofsky and 8-9 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Dow Jones Futures • Futures on the DJIA trade on the Chicago Board of Trade. • The value of stock underlying one DJIA futures contract equals $10 times the futures price. • One tick is one Dow-point, and this equals $10. • Thus, if the DJIA futures price rises one tick, i.e., from 10813 to 10814, a trader who is long one contract profits by $10 because the value of the stock underlying the contract rises from $108,130 to $108,140. ©David Dubofsky and 8-10 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. A Famous Value-Weighted Average: The S&P 500 Stock Index • A widely quoted benchmark portfolio. • Vanguard S&P 500 Trust. • SPDR. (http://www.amex.com). • Standard and Poor’s (S&P) webpage: http://www.standardandpoors.com. ©David Dubofsky and 8-11 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Many Futures Trade on Value-Weighted Indices • Trading on the CME alone: – The S&P 500 futures (the future’s face value is $250 times the S&P 500 index level) – Mini-S&P 500 futures (the future’s face value is only $50 times the S&P 500 index level) – The S&P Midcap 400 (400 middle-sized firms) – Nasdaq 100 (100 Largest Nasdaq Stocks) – Russell 2000 (small cap stocks) ©David Dubofsky and 8-12 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. S&P 500 stock index futures contracts • Perhaps the most actively traded stock index futures in the world. • The last trading day for this contract is the Thursday before the third Friday of the delivery month. • Therefore, there are four delivery months: – – – – March June September December ©David Dubofsky and 8-13 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Marking to Market • The smallest allowed price change (the “tick”) is 0.10 point, which equals $25. • Thus, if the S&P 500 futures price falls from 1,019.40 to 1,019.30, the face value of the futures contract declines $25. That is: (1,019.40)(250) = $254,850 (1,019.30)(250) = $254,825 • This one tick decrease in the futures price creates a mark to market profit of $25 for an individual who is short one contract. ©David Dubofsky and 8-14 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Portfolio Risk Management Using Stock Index Futures • Portfolio managers often have reasons for selling parts of their portfolio. For example: a) b) c) They may feel some stocks no longer offer adequate returns for the risks the stocks possess; They may have turned bearish (or less bullish) on the overall market, or; They may have to sell in order to provide cash for their clients. Stock index futures provide an efficient means to achieve their objectives for reasons b) and c) above. ©David Dubofsky and 8-15 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Stock index futures are also surrogates for the stock purchases when the portfolio manager: a) has received an inflow of cash but has not decided which stocks or market sectors in which to invest. b) has a growing bullishness about the market. c) wants to get market exposure in advance of a near-term expected cash inflow. d) wants an investment that can be quickly liquidated to raise cash, if needed. ©David Dubofsky and 8-16 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Changing the Beta of a Portfolio • Capital Market Theory predicts that rational investors will only hold combinations of two assets: – The market portfolio of all assets, (by definition, has a beta of 1.0) – A risk-less asset, (by definition, has a beta of 0.0) • If investors are relatively more risk averse or are bearish about the prospects for the stock market, investors will lower the beta of their portfolio by shifting a portion of their assets into risk-less securities. • If investors are not very risk averse or if they are bullish about the market, investors will raise their portfolio's beta by borrowing additional capital and investing the borrowed funds in risky securities. ©David Dubofsky and 8-17 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Example: Adjusting the Beta of a Portfolio with Stock Index Futures • Portfolio managers adjust their portfolio betas as they perceive risk and return changes. • When they are bullish, i.e., they believe that the stock market offers a relatively high expected return for a given level of risk, they will increase the beta of their stock portfolio. • When they are bearish, (or simply believe that the risk of the market has increased), they will decrease their portfolio's beta. ©David Dubofsky and 8-18 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Equation to Adjust Beta: • A negative number indicates that futures should be sold in order to lower the portfolio beta. A positive number means that futures should be bought. N= βD - βP βF × Portfolio Value (Futures Price) × Multiplier • Note: Generally, bF = 1, and the Futures Multiplier for the S&P500 is 250. ©David Dubofsky and 8-19 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Using the Equation, I. • A portfolio manager is concerned that the stock market will temporarily decline in the next few days. • The manager does not wish to incur the commission costs and price pressure of selling stocks and then repurchasing them after the anticipated decline. • Thus, the manager decides to use futures contracts to hedge against the expected market decline. ©David Dubofsky and 8-20 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Using the Equation, II. • An equity fund manager owns a portfolio of $20 million in stocks with a portfolio beta of 1.20. • Suppose, the S&P 500 index level is 1275 and the observed futures price is 1280. What is the risk-minimizing position? N= 0.0 - 1.20 1 × $20,000,000 = -75. (1280) × 250 • The Key: Set the target portfolio beta, bd, equal to 0.0. Then, using the equation above, we conclude that the manager should sell 75 futures contracts. • Suppose the manager was right about the market's movement, and the S&P 500 declines to 1224, which is a 4% decline in the market. ©David Dubofsky and 8-21 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Using the Equation, III. • If beta was estimated accurately, the value of the manager’s equity portfolio should decline by 4.8% (1.20 times 4%). This results in a loss in the capital value of the portfolio of $960,000. • Now assume that the futures price also declines by 4%, to 1228.80. • A futures price decline of 51.2 points results in a profit of $12,800 on one futures contract. On a position of 75 short futures contracts, the profit would be $960,000. • Here, the hedge eliminated the effects of the market decline. ©David Dubofsky and 8-22 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Stock Index Arbitrage • Stock Index Arbitrage is an attempt to exploit any futures mispricing relative to the index level. • When futures prices lie outside their no-arbitrage bounds, arbitrageurs will quickly act to realize the (near) riskless profits by buying cheap stock and selling futures (buy programs), or buying cheap futures and selling stock (sell programs). • Between July 1, 2002 and August 30, 2002, program trading averaged 34.6% of total NYSE volume, and stock index arbitrage as a percentage of total program trading ranged between 8.4% and 14.3%, with an average of 11.9%. ©David Dubofsky and 8-23 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Arbitrage Bounds • In practice, if F > S + CC - CR, then arbitrageurs' purchases of stock increase stock prices (these are called “buy programs”). • Their sales of futures will depress futures prices, until equilibrium is again reached (F S + CC - CR), and no arbitrage opportunities exist. • Similarly, if F < S + CC - CR, the buying of cheap futures and the sale of expensive stock (“sell programs”). • Their purchases of futures will increase futures prices, until equilibrium is again reached (F S + CC - CR), and no arbitrage opportunities exist. ©David Dubofsky and 8-24 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Program Trading • Program trading is a technique for trading a stock portfolio in one single order. • The NYSE defines a program trade as: "a wide range of portfolio trading strategies involving the purchase or sale of a basket of 15 stocks or more, and valued at more than $1 million". • Program trading may involve stock index arbitrage, option replication strategies, or asset allocation shifts (such as between equities and bonds), etc. • Recent growth in program trading has arisen from brokers who offer institutions the ability to trade large portfolios of stocks with low cost and little price impact. • In 2001, program trading accounted for almost 30% of total NYSE volume. ©David Dubofsky and 8-25 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. An Actual Pricing Example, 2/5/99 • • • • • SPH: 1,243.50 S&P Index: 1,239.40 T-bill rate: 4.35% Days to Expiration: 42 Annual Dividend Yield: 1.32% (assume this is the dividend yield in terms of its future value) What is the theoretical futures price, and the Deviation from Fair Value (DFV)? ©David Dubofsky and 8-26 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. DFV = Factual – Ftheoretical • • • • Let t = the time until delivery, in years. Note that dividends = dtS Ftheoretical = S + Srt – Sdt Ftheoretical = 1239.40 + (1239.40)(0.0435)(42/365) (1239.40)(0.0132)(42/365) = 1243.72 • Fobs is ‘too low’ by –0.22 index points. • So, if TC are less than 0.22 to perform reverse cash and carry arbitrage, then do it! ©David Dubofsky and 8-27 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Index Arbitrage with Transaction Costs • Let hb and hl = the unannualized borrowing rate and lending rate, respectively. • Let Sbid and Sask = the spot index value, based on stocks’ bid quotes and asked quotes, respectively. • Let TC1 and TC2 = transaction costs (commissions, etc.) necessary to perform reverse cash and carry arbitrage, and cash and carry arbitrage, respectively. • Sbid (1+hl(0,T)) - div(1+hb(,T)) - TC1 < F < Sask(1+hb(0,T)) - div(1+hl(,T)) + TC2 ©David Dubofsky and 8-28 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. The DOT • In 1976, the New York Stock Exchange introduced its Designated Order Turnaround (DOT) system, which was improved and renamed Super DOT in November 1984. • Super DOT is a computerized order handling system that guarantees that any market order of less than 2100 shares of a stock will be executed within three minutes at the prevailing bid price (for a market sell order) or asked price (for a market buy order) at the time the order was entered, or at better prices if possible. • Today, the average order through SuperDot is transmitted, executed and reported back to the originating firm in 22 seconds. ©David Dubofsky and 8-29 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. DOT and Stock Index Arbitrage • Originally, DOT was designed to alleviate the traffic around specialists' trading posts by automatically handling the orders of small individual investors. • Runners do not have to hand-carry small orders to the specialist. Instead, they are electronically transmitted from order rooms to the specialists' posts. • Little did the designers of DOT realize that their system would be adopted by index arbitrageurs, who now enter orders to buy or sell portfolios of stocks, including the composition of any index replicating portfolio (e.g., 1000 shares of IBM, 1267 shares of GM, etc.). ©David Dubofsky and 8-30 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Computerized Trading • Whenever an arbitrage opportunity arises a trader can literally push a button to submit these orders to buy (at the asked) or sell (at the bid) the entire basket of stocks. • On average, the execution of the trade is reported back to the buyer or seller in 22 seconds. • At the same time, the arbitrageur will trade the necessary stock index futures contracts. • Larger orders (more than 2099 shares of one stock) are handled less efficiently, with trades occurring only after an arbitrageur's human representative carries the order to the specialists' posts. ©David Dubofsky and 8-31 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Risks of Stock Index Arbitrage • Even with Super DOT, there are some risks to index arbitrage. Large orders to trade securities are not guaranteed any price, and prices can change quickly in the few minutes that it takes to execute all of the desired trades. • Arbitrageurs' orders to buy stock may create upward price pressure on those stocks unless there happens to be a contemporaneous flow of sell orders, or the specialist is willing to reduce his inventory of stock. • Similarly, program selling will often lead to price declines in the spot stock market. ©David Dubofsky and 8-32 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Some Extra Slides on this Material • Note: In some chapters, we try to include some extra slides in an effort to allow for a deeper (or different) treatment of the material in the chapter. • If you have created some slides that you would like to share with the community of educators that use our book, please send them to us! ©David Dubofsky and 8-33 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Three Basic Weighting Schemes • Capitalization-Weighting (AKA Value Weighting or Market-Value Weighting): – Stocks held in proportion to their market value. – Large-cap companies have more influence on the index. ©David Dubofsky and 8-34 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Three Basic Weighting Schemes, Cont. • Price Weighting: Equal number of shares invested in each stock, therefore, the price is the weight. – The highest-priced stocks have the largest weight. – Berkshire Hathaway • Equal Dollar Weighting: Same dollar investment in each stock. – The lowest-priced stocks have more influence. ©David Dubofsky and 8-35 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Assume a $1,000,000 Portfolio, Value-Weighting, Data from 3/11/1994 Company Price Shares Capitalization Value Value (millions) (millions) Weight Shares Am. Express 28.625 485.445 13,895.9 0.0560 1,956 GE 105.250 852.935 89,771.4 0.3618 3,437 3M 103.250 215.791 22,280.4 0.0898 870 Merck 32.125 1,282.316 41,194.4 0.1660 5,167 Exxon 65.250 1,241.618 81,015.6 0.3265 5,003 248,157.7 1.0000 16,434 Total: 334.500 Total: Note: Shares = $1,000,000*Weight / Price ©David Dubofsky and 8-36 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Assume a $1,000,000 Portfolio, Price-Weighting, Data from 3/11/1994 Company Am. Express Price Price Price-Weighted Weight Shares 28.625 0.086 2,990 GE 105.250 0.315 2,990 3M 103.250 0.309 2,990 Merck 32.125 0.096 2,990 Exxon 65.250 0.195 2,990 334.500 1.000 2,990 Note: Shares = $1,000,000 / 334.500 = 2,990 ©David Dubofsky and 8-37 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. DJIA Index Details, I. • The DJIA is computed by adding the prices of the thirty component stocks, and dividing the sum by a divisor. • The divisor is printed in the Wall Street Journal every day and is also available in the equity product information area at http://www.cbot.com. • For example, on April 24, 2001, the divisor for the DJIA was 0.15369402. On September 9, 1999, the divisor was 0.19740463. • The divisor is changed when one of two events occurs. Periodically, one of the thirty stocks in the DJIA may be removed, and another company's stock is substituted. • This will happen when a component stock is taken over by another company or one of the corporations goes bankrupt. ©David Dubofsky and 8-38 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. DJIA Index Details, II. • For example, Anaconda, a component of the DJIA, was bought by Atlantic Richfield (ARCO) in 1976. Thus, a new component stock (which was MMM) was chosen to replace Anaconda. • Dow Jones may decide that the DJIA no longer representative of "the market", so the composition will change. – This occurred on November 1, 1999 – IN: Home Depot, Intel, Microsoft, and SBC Communications – OUT: Chevron, Goodyear, Sears Roebuck, and Union Carbide. • So, anytime there is a change in the portfolio of the constituent stocks, or if there are splits, stock dividends, or mergers, the DJIA divisor will change because Dow Jones and Company wants to remove the impact on the index from these events. • NB: The DJIA is not adjusted to account for regular dividend payments. ©David Dubofsky and 8-39 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Example: Changing the Divisor Day 1 of Index: Company Am. Express GE 3M Merck Exxon Sum: Index: Price 28.625 105.250 103.250 32.125 65.250 334.500 66.90 (Divisor = 5) Before Day 2 starts, we want to replace Merck with Intel, selling at $22. To Keep the value of the Index the same, i.e., 66.90: Am. Express GE 3M Intel Exxon Sum: Sum / Divisor = 66.90 if Divisor is: 28.625 105.250 103.250 22.000 65.250 324.375 4.848654709 ©David Dubofsky and 8-40 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. DJIA Index Details, III. • To construct a portfolio that is equivalent to the DJIA, an investor must buy an equal number of shares of each of the component stocks. • Maintaining the proper underlying portfolio is complicated by the payment of cash dividends and stock distributions. • Still, the DJIA is an easy index to replicate, as it has only 30 stocks, each of which is very actively traded. • If a stock selling for $100/share increases in value by 5%, then the DJIA will increase by 5/divisor points. • If a stock selling for $20/share rises in price by 5%, then the DJIA will rise by only 1/divisor points. ©David Dubofsky and 8-41 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Assume a $1,000,000 Portfolio, Equal-Weighting, Data from 3/11/1994 Company Am. Express Price Equal Equal-Weighted Weight Shares 28.625 0.200 6,987 GE 105.250 0.200 1,900 3M 103.250 0.200 1,937 Merck 32.125 0.200 6,226 Exxon 65.250 0.200 3,065 1.000 20,115 Shares = $1,000,000*0.20 / Price ©David Dubofsky and 8-42 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Many stock market indices are ValueWeighted Averages • In the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), a stock's correlation with the market portfolio is the factor that determines its price, and that market portfolio is value-weighted. • Besides the NYSE and S&P Indices, other value-weighted indices include the AMEX Market Value Index, the NASDAQ Composite Index, the Russell 2000 Index, and the Wilshire 5000. • The levels of these and yet other indices are presented daily in the Wall Street Journal. While each index is a different portfolio of stocks, the method of computing each index is the same. ©David Dubofsky and 8-43 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Value-Weighted Index Movements. Day 1: Day 2: Company Price Am. Express 28.625 GE 105.250 3M 103.250 Merck 32.125 Exxon 65.250 Total Shares Market Capitalization (millions) (millions) 485.445 13,896 852.935 89,771 215.791 22,280 1,282.316 41,194 1,241.618 81,016 Total MV(1): 248,158 Divisor (Set by Vendor): 248.1576686 Day 1 Index Level: 1000.00 Company Price Am. Express 29.000 GE 110.000 3M 92.000 Merck 37.000 Exxon 67.000 Total Shares Market Capitalization (millions) (millions) 485.445 14,078 852.935 93,823 215.791 19,853 1,282.316 47,446 1,241.618 83,188 Total MV(2): 258,388 Day 2 Index Level: 1041.22 ©David Dubofsky and 8-44 Thomas W. Miller, Jr. Note Bene: The Day 3 index can be calculated in two ways: Day 3: Company Am. Express GE 3M Merck Exxon Price 25.000 108.500 93.700 37.875 62.000 Total Shares Market Capitalization (millions) (millions) 485.445 12,136.1 852.935 92,543.4 215.791 20,219.6 1,282.316 48,567.7 1,241.618 76,980.3 Total MV(3): 250,447.2 Day 3 Index Level: 1009.23 Day 2 Index Market Value Day 2 Index Level Day 1 Market Value Day 1 Day 2 Index Market Value Day 2 Index Level Day 0 Market Value Day 0 ©David Dubofsky and 8-45 Thomas W. Miller, Jr.