Political Parties and Voting. 3 factors that distinguish political parties

advertisement

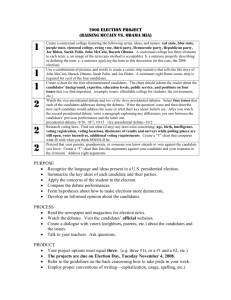

Political Parties and Voting. 3 factors that distinguish political parties from other political organizations: 1) they run candidates under their own label 2) They have platforms 3) Subject to state and local law. What do parties do? 1) Shape the election process 2) Facilitate voter choice 3) Recruit Candidates 4) Aid Candidates 5) Educate Citizens 6) Organize Complex Government 7) Ensure Accountability and Choice -RNC and DNC HISTORY OF POLITICAL PARTIES - Emergence of Parties (1790’s-1828) Democratic-Republicans (opponents of John Adams) vs. Federalists - 1828 – 1900 Corrupt Bargain of 1824 – Rise of the Whig Party, Democratic Republicans -> National Republicans -> Democratic Party (led by Andrew Jackson). - 1900 – 1970’s The decline of the merit system, The New Deal, Candidate – Centered Era - 1970’s – Present Resurgence of the Party system. VOTING and ELECTIONS - 14th equal protection under the law for US citizens - 15th rights to vote may not be denied based on race - 19th women’s rights to vote - 24th elimination of the poll tax - 26th – 18 year old citizens can vote - Voting Rights Act 1965 Voter Turnout – 57% in 2012 – Reasons for low turnout Voter Demographics Why do Americans vote in small numbers? Political scientists have suggested a number of reasons: Inconvenience: For many, getting to the polling place on election day is very difficult: Many people have to work, and some have trouble getting to their precinct. Registration: All voters must register ahead of the election (sometimes a month or more in advance); the registration process can be confusing and at times difficult to follow. Similarity of the parties: Some citizens believe the parties are very similar, so voting will not make a difference Alienation: People do not vote because they feel that the government does not care about them or listen to their concerns. Frequency of elections: Americans hold elections more frequently than most other democracies; voters find it difficult to vote on so many different days. Lack of competitiveness: Many races in the United States are very lopsided, so voters are likely to stay home, thinking the outcome is a foregone conclusion. The ballots used in elections have changed significantly in American history. Originally, political parties printed their own ballots, listing only their candidates. Voters took ballots from the party of their choice and deposited them in the ballot box within full view of other voters. As a result, vote choices were public. Since 1888, however, state governments have printed ballots that list all candidates for all offices. Votes are cast in secret. Because Australia was the first country to adopt the secret ballot, this ballot is called the Australian ballot. Elections in the United States use one of two kinds of Australian ballots: The office-block ballot (also called the Massachusetts Ballot): Candidates are grouped by office. The party-column ballot (also called the Indiana Ballot): Candidates are grouped by party. Political parties do not like office block ballots because these ballots encourage people to vote for candidates from different parties (a practice known as split-ticket voting). Instead, political parties prefer party-column ballots because these ballots make it easy to choose candidates only from a particular party. Some of these ballots even allow voters to choose all of a party’s candidates by checking a single box, or pulling a single lever, a practice called straight-ticket voting. Partisan Battles over Ballots Political parties tend to support whatever ballot helps them get the most votes. In the 1998 election, the Democratic Party in Illinois won big, in part because of a very effective campaign to get voters to vote straight-ticket Democrat. After the election, Republicans in the Illinois state legislature sought to forbid those ballots with a single box, which allowed a straight-ticket vote. Voting Machines Americans vote using a wide variety of machines: Mechanical voting machines: Voters flip switches to choose candidates and then pull a lever to finalize their vote. Punch-card machines: Voters mark their choices on a card using a pencil and then deposit their cards into a machine, which then tallies the vote based on the card’s holes. Touch-screen machines: Similar to ATMs, these increasingly popular machines “read” the voters’ choices. But these methods have serious problems. Mechanical voting machines frequently break down, but many of the companies that made the machines have gone out of business. Punch-card machines are fallible because punching does not always create a complete hole (leading to debates about hanging and pregnant chads, as in the 2000 presidential elections). Many computer security experts see touch-screen voting as dangerously insecure. Others point out that most touch-screen machines leave no paper documents, a huge problem in cases of recounts. Florida 2000 The 2000 election in Florida and other states was shocking because of the inconsistency and imprecision of voting in many jurisdictions. Even within a single state, precincts use a wide variety of voting machines. And jurisdictions often have very different rules for counting votes and holding recounts. After the 2000 election, many wanted to standardize voting, but so far little has been done for one major reason: cost. Purchasing the same voting machines for all precincts would be prohibitively expensive. Absentee Ballots Traditionally, people vote by filling out a ballot at their local polling precinct or voting center. But some voters, such as college students or people serving in the military, cannot get to their polling place to vote. The states allow these voters to use absentee ballots. Absentee voters usually receive their ballots in the mail several weeks before the election, fill them out, and mail them back to state election officials. Voting by Mail Usually states have provided absentee ballots to those who had good reasons for not being able to go their polling place. In recent years, though, some states have made it easy for anyone to vote by mail, in an effort to encourage voting. In 2000, for example, Oregon allowed all voters in the presidential election to mail in their ballots. Voter participation surpassed 80 percent, a remarkable number. Due to this success, Oregon has completely abandoned precinct voting. But voting by mail has its critics. These people argue that voting by mail allows people to make their final choice early in the campaign, before debates or other events that could substantially change the race. Still others feel that voting in person at precincts builds a sense of civic-mindedness, which is not possible through voting by mail. Supporters of voting by mail argue that the increased turnout outweighs these criticisms. Online Voting Many people think the future of voting is on the Internet, which would allow people to vote as easily and quickly as they send email. Some states have experimented with online voting. Critics fear that online voting has the potential to compromise the secret ballot or to encourage voter fraud, and so online voting remains in its experimental stages. ELIGIBILITY REQUIREMENTS FOR FEDERAL OFFICES Office Requirements Representative At least 25 years old, a citizen for at least 7 years, and a resident of the state he or she represents Senator At least 30 years old, a citizen for at least 9 years, and a resident of the state he or she represents President and Vice President 14 years At least 35 years old, a natural-born citizen, a U.S. resident for at least Traits of Office Seekers Most elected officials are older, white males and usually wealthier than the average citizen. In the last few decades, more women and minorities have taken office at the state and federal levels, but they hold office in disproportionately low numbers. Following the 2002 elections, for example, just sixty-two women served as members of the House. After the 2004 elections, only one African American served in the Senate. The homogeneity of officeholders does not reflect the diversity of the population of the United States. Professional, Ambitious, and Driven Most people who run for office are professionals, such as businesspeople, doctors, and, above all, lawyers. Blue-collar workers and manual laborers occasionally run for office, but not in proportion to their numbers. Because they are predominantly professionals, candidates are, on the whole, more educated than the average citizen. Political Scientist as Politician Thus far, only one president has had an academic background. Woodrow Wilson held a PhD in political science and both taught at and served as the president of Princeton University before entering politics. All office seekers, however, are ambitious. Running for office—even a low-level one—is extremely demanding. Only people with a strong commitment to winning will put up with the intense schedule of campaigning. At higher levels, candidates face even more challenges. Example: Presidential candidates often campaign for eighteen hours a day. But the last few days of a presidential campaign are particularly grueling. Candidates give up sleep to campaign nonstop for the last few days. At the end of the 2000 campaign, Democrat Al Gore campaigned for forty-eight hours straight, attending rallies at all hours of the day. His opponent, Republican George W. Bush, followed a similarly grueling schedule. Presidential Candidates The longest, most difficult, most expensive, and most visible campaigns are those for president. The process begins when a candidate chooses to run. Then he or she must win the party nomination, endure the primaries, attend the national convention, and, ultimately, campaign in the general election. Choosing to Run Candidates usually spend the two years before the first primary raising money, cultivating support from important party activists, and getting their name known by the public. Many people spend a number of months preparing to run for office only to eventually decide not to run because they cannot generate enough support or they find the process too demanding. Winning the Nomination After candidates enter the race, they must fight for the party’s nomination with the other candidates. Before 1972, party leaders chose nominees through negotiation and compromise. Since the early 1970s, the parties have opened up the nomination process to voters through primary elections: The winner of a primary becomes the party’s nominee. In a closed primary, only party members may vote; most states hold this type of primary. In an open primary, all voters, regardless of party, may vote as long as they participate in only one primary. In the presidential campaign, a candidate must win a majority of convention delegates in order to win the nomination. Each state holds either a primary or caucuses (meetings of party members to select a candidate). Candidates win a number of delegates based on how many popular votes they receive in these primaries; these delegates go to their party’s national convention to vote for the party’s nominee. The candidate with the most delegates wins the nomination. Superdelegates are prominent party members (including elected officials and party organization leaders) who automatically get to vote in the national convention. Winning delegates also helps candidates raise money: The more delegates they win, the more legitimate they appear as contenders. The candidate who appears to have the lead is called the front-runner. The Big Mo Momentum—dubbed “the big mo” by President George H. W. Bush—is crucial in the primary campaign. Supporters will often abandon a candidate who appears to be faltering. Momentum seems to have a life of its own: A candidate who has momentum surges forward, even if other candidates have more money or endorsements. Often, a candidate who gets momentum early can run away with the race. In most presidential campaigns, the eventual winner is apparent long before the final primaries. Front-Loading Primaries Over the past few election cycles, many states have moved their primaries up to an earlier date, a process called front-loading. Due to front-loading, the nominations are decided early, usually by the end of March, even though the national conventions do not meet until late summer. States do this in order to maximize the impact they have on the nomination. States with primaries toward the end of the campaign have little impact because one candidate has emerged as the clear winner. Front-loading also limits the time in which party members disagree about candidates and potential nominees, allowing the party to unite in preparation for the general election. Example: In 1988, a group of southern states agreed to hold their primaries on the same day, early in the campaign, in order to increase the chance of nominating a moderate southerner. Since then, many states have held primaries on the same date in March, now known as Super Tuesday, during the election year. The National Convention Every four years, the major parties hold massive conventions, whose major purpose is to choose the party’s nominees for president and vice president. Delegates from across the country arrive, meet with party leaders, and vote on a number of matters. The credentials committee established by each party decides which delegates are legitimate and therefore allowed to participate. Delegate Controversy Most of the time, certification by the credentials committee is a formality. Every now and then, however, a dispute arises that forces the credentials committee to make unpleasant choices. At the 1964 Democratic convention, for example, two different slates of delegates claimed to represent Mississippi: an all-white group opposed to civil rights and a mixed-race group supporting civil rights. In this case, the credentials committee accepted the pro–civil rights group, but in doing so, they alienated many southern whites. Parties officially nominate their candidates at national conventions. Delegates chosen in primaries gather together and vote for the party’s nominees; they also approve their party’s platform. In theory, conventions could be bitterly fought affairs, but in practice, the voting is a formality: By that point, the party’s nominee has become clear. Conventions have become highly staged and scripted and serve primarily to rally the party behind the nominees. The General Election Campaign The general election commences after the conventions. Candidates from Republican, Democratic, and independent parties vie for votes by giving speeches, shaking hands, holding rallies, proposing policies, courting the media, and debating one another. In modern campaigns, the media relentlessly follows candidates and polls likely voters, so coverage often seems akin to sports reporting on pennant races. Many voters rely heavily on the debates to make their choice. Debates in the Television Age Although presidential candidates have debated for a long time, the television age changed the character of debates. In 1960, the debates were broadcast for the first time on television. Many people were drawn to the visual appeal of John F. Kennedy: He appeared attractive, athletic, and confident, while Nixon (who was suffering from the flu) appeared uncertain and unattractive. Many famous moments in recent political history occurred during the debates. In 1980, for example, Republican Ronald Reagan began his attack on Democrat Jimmy Carter by saying, “There you go again,” to thunderous applause. George H. W. Bush, meanwhile, hurt himself in the televised presidential debates when he repeatedly looked at his watch while Bill Clinton was speaking. Even though Bush was merely timing Clinton’s speech, many viewers misinterpreted the action as a reflection of boredom and disinterest, which led to drop in the polls for Bush. The Electoral College The Electoral College officially decides the presidential election. Each state has the same number of electoral votes as it has total seats in Congress. In most states, all of the state’s electoral votes are awarded to the presidential candidate who receives the most popular votes in that state, whereas the losing candidates receive none. Presidential candidates, therefore, usually focus their energies on winning the popular vote in the large states that have many electoral votes or in states in which the voters are deeply divided. Republicans stand little chance of winning liberal California and New York, for example, and Democrats are no longer popular in conservative Texas, but both parties have spent millions of dollars on campaigns in recent presidential elections in the populous swing states of Florida and Ohio. Campaign Finance Reform Political campaigns, especially presidential ones, cost a lot of money to run. During the 2004 presidential race, for example, both major party candidates spent more than $100 million. Generally, the candidate with the bigger war chest tends to win the race. Campaign finance laws limit the amount of money people and corporations may donate to a campaign, as well as dictate how candidates may spend that money. Early Attempts at Regulating Campaign Finance For much of American history, there were no regulations at all on campaign finance: Anyone could give as much as he or she wished, and candidates could spend all they had in any way they saw fit. Two landmark laws in the early twentieth century regulated campaign finance for the first time: The corrupt practices acts: This series of laws, starting in 1925, limited expenditures by congressional candidates and controlled corporate contributions to candidates. The Hatch Act: Passed in 1939, this act limited the political actions of federal civil servants and restricted contributions by political groups.