Mercer - Submission to the Financial System Inquiry. Issues set out

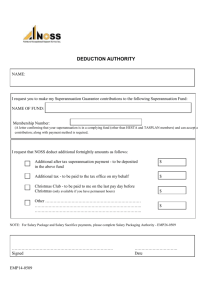

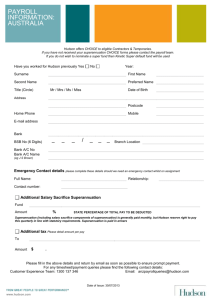

advertisement