The Death of Orpheus (Ovid)

advertisement

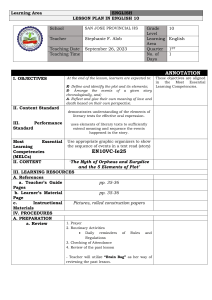

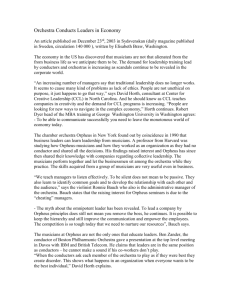

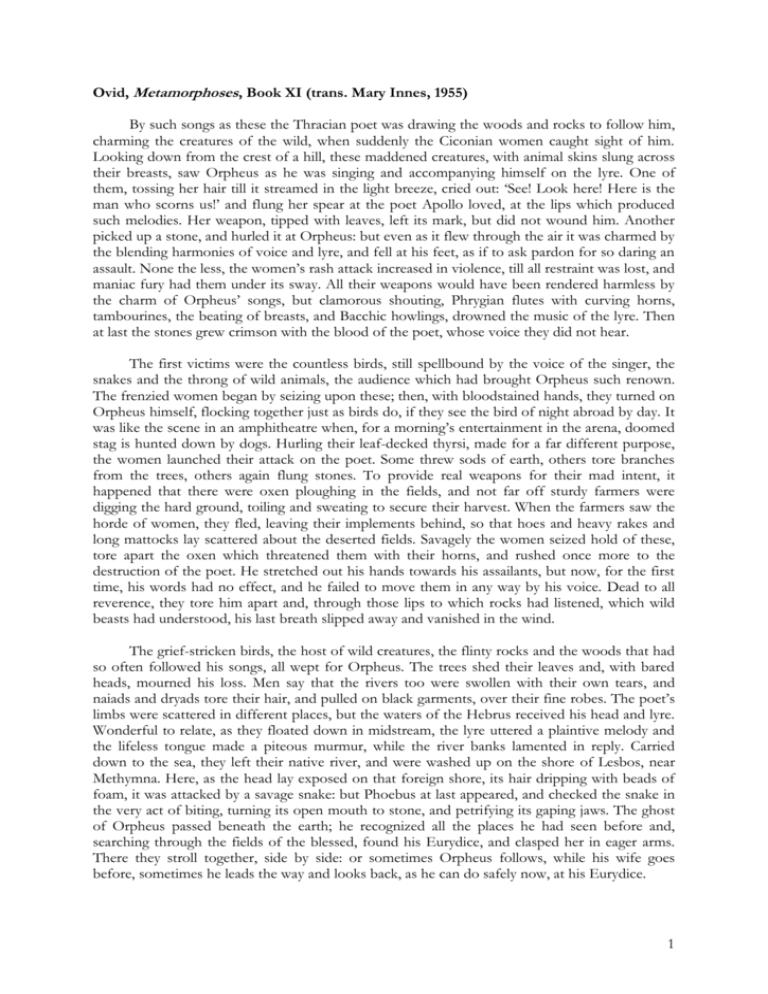

Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book XI (trans. Mary Innes, 1955) By such songs as these the Thracian poet was drawing the woods and rocks to follow him, charming the creatures of the wild, when suddenly the Ciconian women caught sight of him. Looking down from the crest of a hill, these maddened creatures, with animal skins slung across their breasts, saw Orpheus as he was singing and accompanying himself on the lyre. One of them, tossing her hair till it streamed in the light breeze, cried out: ‘See! Look here! Here is the man who scorns us!’ and flung her spear at the poet Apollo loved, at the lips which produced such melodies. Her weapon, tipped with leaves, left its mark, but did not wound him. Another picked up a stone, and hurled it at Orpheus: but even as it flew through the air it was charmed by the blending harmonies of voice and lyre, and fell at his feet, as if to ask pardon for so daring an assault. None the less, the women’s rash attack increased in violence, till all restraint was lost, and maniac fury had them under its sway. All their weapons would have been rendered harmless by the charm of Orpheus’ songs, but clamorous shouting, Phrygian flutes with curving horns, tambourines, the beating of breasts, and Bacchic howlings, drowned the music of the lyre. Then at last the stones grew crimson with the blood of the poet, whose voice they did not hear. The first victims were the countless birds, still spellbound by the voice of the singer, the snakes and the throng of wild animals, the audience which had brought Orpheus such renown. The frenzied women began by seizing upon these; then, with bloodstained hands, they turned on Orpheus himself, flocking together just as birds do, if they see the bird of night abroad by day. It was like the scene in an amphitheatre when, for a morning’s entertainment in the arena, doomed stag is hunted down by dogs. Hurling their leaf-decked thyrsi, made for a far different purpose, the women launched their attack on the poet. Some threw sods of earth, others tore branches from the trees, others again flung stones. To provide real weapons for their mad intent, it happened that there were oxen ploughing in the fields, and not far off sturdy farmers were digging the hard ground, toiling and sweating to secure their harvest. When the farmers saw the horde of women, they fled, leaving their implements behind, so that hoes and heavy rakes and long mattocks lay scattered about the deserted fields. Savagely the women seized hold of these, tore apart the oxen which threatened them with their horns, and rushed once more to the destruction of the poet. He stretched out his hands towards his assailants, but now, for the first time, his words had no effect, and he failed to move them in any way by his voice. Dead to all reverence, they tore him apart and, through those lips to which rocks had listened, which wild beasts had understood, his last breath slipped away and vanished in the wind. The grief-stricken birds, the host of wild creatures, the flinty rocks and the woods that had so often followed his songs, all wept for Orpheus. The trees shed their leaves and, with bared heads, mourned his loss. Men say that the rivers too were swollen with their own tears, and naiads and dryads tore their hair, and pulled on black garments, over their fine robes. The poet’s limbs were scattered in different places, but the waters of the Hebrus received his head and lyre. Wonderful to relate, as they floated down in midstream, the lyre uttered a plaintive melody and the lifeless tongue made a piteous murmur, while the river banks lamented in reply. Carried down to the sea, they left their native river, and were washed up on the shore of Lesbos, near Methymna. Here, as the head lay exposed on that foreign shore, its hair dripping with beads of foam, it was attacked by a savage snake: but Phoebus at last appeared, and checked the snake in the very act of biting, turning its open mouth to stone, and petrifying its gaping jaws. The ghost of Orpheus passed beneath the earth; he recognized all the places he had seen before and, searching through the fields of the blessed, found his Eurydice, and clasped her in eager arms. There they stroll together, side by side: or sometimes Orpheus follows, while his wife goes before, sometimes he leads the way and looks back, as he can do safely now, at his Eurydice. 1 However, Bacchus did not allow this crime to go unpunished. He was distressed at losing the poet who had sung his mysteries, and immediately all the Thracian women who had watched the scene were fastened to the ground, there in the woods, by means of gnarled roots. The god drew out their toes, as far as each had followed Orpheus, and thrust the tips down into the solid earth. Just as a bird, finding its legs caught in the hidden snare of some cunning fowler, beats its wings when it feels itself held, and tightens the bonds by frightened fluttering, so each of the women, as she became rooted to the spot, went mad with fear, and vainly tried to flee, while the tough root held her fast, preventing her attempts to pull herself away. Each one of them, as she looked for her toes, her feet and nails, saw wood spreading up her shapely legs: when she tried to smite her thighs, in token of her grief, she struck against the bark of an oak tree. Their breasts, too, and likewise their shoulders turned to oak; their arms appeared to have been changed into long branches, as indeed they were – it was no illusion. Even this was not enough for Bacchus. He abandoned the very fields of Thrace and, with a band of more seemly revellers, betook himself to the vineyards of his beloved Tmolus, and to the river Pactolus, though it was not then rich in gold, or envied for its precious sands. He was attended by his usual throng, satyrs and bacchants, but Silenus was not there. For Phrygian peasants had captured him, as he tottered along on feet made unsteady by age and wine. They had bound him with chains of flowers, and taken him to their king Midas, who had once been instructed in the Bacchic mysteries by Orpheus from Thrace, and by the Athenian Eumolpus. When Midas recognized him as one who was the god’s companion and partner in his mysteries, he celebrated the arrival of such a guest with continuous festivities for ten days and nights on end. On the eleventh day, when Lucifer had shepherded away the flock of stars on high, the king came to Lydia, in great good humour, and restored Silenus to his young ward. The god was glad to have his tutor back, and in return gave Midas the right to choose himself a gift – a privilege which Midas welcomed, but one which did him little good, for he was fated to make poor use of the opportunity he was given.… 2