An Introduction to Argument

advertisement

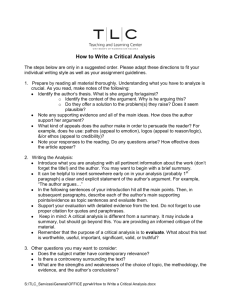

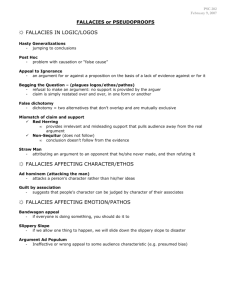

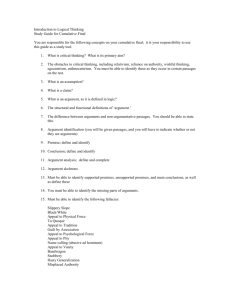

An Introduction to Argumentation Participating in Academic Discourse Intro to Argument • • • • • • • • Argument Survey (3) Why study argument? (4) Argument vs. Persuasion: Appeals (7) Logical Appeals (10) Common Fallacies (16) Methods of Logical Argument (19) Emotional Appeals (25) Ethical Appeals (28) 2 Argument Survey 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Answer the following questions on your own paper. What is the purpose of argumentation? How are argument and exposition related? How are argument and persuasion related? How are argument and research related? How does an author appeal to an audience? What is a logical fallacy? What are the characteristics of a strong argument? What are different methods of “arguing”? 3 Why study argument? • • • • University professors, frustrated with first-year students’ inability to craft a balanced, reasoned argument, have observed that many students: confuse argument with opinion, writing self-oriented rather than reader-based papers; were black and white thinkers, unable or unwilling to address the complexities of an issue; jump on the bandwagon, going with the first authority they find without considering other points of view; Defend weak arguments simply because “it’s my opinion and I have a right to it.” 4 From “Everything’s an Argument” All language has an argumentative edge that aims to make a point. From bumper stickers, to signage, to the statement “This won’t hurt a bit,” visual and verbal messages all contain arguments. Some argue that every text is an argument, designed to influence readers. It’s important to realize that argument isn’t just about winning, it can also be about informing, convincing, exploring, and making decisions. 5 From “Everything’s an Argument” There is a distinction between argument and persuasion. The point of argument is to discover some version of the truth, using evidence. Argument leads audiences towards conviction, an understanding that the claim is reasonable. The point of persuasion is to change a point of view in order to move others from conviction to action. In other words, writers or speakers argue to find truth, and persuade others when they think they already know a truth. Argument (discover a truth) -> conviction Persuasion (know a truth) -> action 6 Argumentation continuum FORMAL ARGUMENT To explain/defend a credible conclusion to a general audience based on synthesis of multiple perspectives Clearly stated assertions/premises Definition Logical appeals only Fair consideration of multiple perspectives ELEMENTS Purpose and Audience Content PERSUASION To convince a specific audience to accept an opinionthesis (reject an antithesis) or take action Assertions often implied Connotation Balance of appeals Direct refutation of opposing positions7 FORMAL ARGUMENT Establishes relevance of proposition/conclusion Linear organization based on reasoning or development method Formal diction/word choice Objective tone (attempt to appear as unbiased as possible) Summary of premises/conclusion ELEMENTS Organization Style Conclusion PERSUASION Hooks reader into a clearly stated position Builds in emotional intensity to a high point Level of diction relative to audience/purpose Subjective tone (persuasive but not antagonistic) Call to action 8 Types of Appeals • Logical Appeal (Logos): An appeal based on logic that presents reasons for an opinion or conclusion and evidence to support them. (Appeal to the HEAD) • Emotional Appeal (Pathos): appeals to the feelings of readers to drive them to action. (Appeal to the HEART) • Ethical Appeal (Ethos): reflects the image you as the writer projects to the audience to gain their support; asks the audience to trust or believe you based on the transparency of your actions. (Appeal to the GUT) 9 The Logical Appeal The Language of Argument Adapted from Weston, Anthony. A Rulebook for Arguments. 3rd ed. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 2000. An opinion is something you have … it is an individual judgment made on personal beliefs. An argument is something you construct. While opinions don’t always have bases (these are often referred to as prejudices), arguments are a form of discourse and must be built through logical reasoning supported by evidence. • Discourse: a formal treatment of a subject communicating key ideas or information 10 The Logical Appeal The Language of Argument A formal argument states a proposition, develops that proposition with premises, and based on the connection of the premises comes to a conclusion. • Proposition: What you are trying to show/prove • Premise: Statements of reason used to support a conclusion • Conclusion: The end result based on reasoning/evidence 11 The Logical Appeal The Language of Argument Formal arguments are constructed through logical reasoning. • Reasoning: the process by which premises are connected/related to construct an argument • Inductive: going from specific examples to general conclusions (scientific method, analogy) • Deductive: specific conclusion inferred from general premises (syllogism) • Analogy: conclusions drawn from shared characteristics based on an extended comparison 12 The Logical Appeal The Language of Argument Logical reasoning is supported by evidence. 1. FACTS: Information that no one can seriously dispute. – CAUTION: Don’t overwhelm your reader. Be concise and precise. 2. AUTHORITIES: Views held by recognized experts in a particular field. – CAUTION: Beware of biased opinions. Establish the credibility and reliability of your source first. 3. PRIMARY SOURCES: Documents and materials produced by those directly involved with the issue or conclusions reached through your own investigative efforts. – CAUTION: Make sure you are representing the original information accurately and fairly. 13 The Logical Appeal The Language of Argument 4. STATISTICS: Collected data used to make generalizations or support a point, usually answering questions such as how much, how many, or how often. – CAUTION: These are often misused, or misrepresented, and therefore may be distrusted. Check for size of data samples, relevance of results, credibility of sources, and currency of data. 5. PERSONAL EXPERIENCE: Using the experiences and observations of yourself and others to support a position. – CAUTION: These first-hand accounts may be seen as atypical or trivial, so should be used to support other forms of evidence. 14 The Logical Appeal The Language of Argument For arguments to be valid, the reasoning they are constructed upon must be free of fallacies. • Fallacy: any violation of or lapse in logical reasoning (usually expressed in an annoying Latin phrase) 15 The Logical Appeal Common Fallacies There are many logical fallacies, but here are the twelve you will need to know! • Hasty generalization: The writer bases his/her argument on insufficient or unrepresentative evidence. • Non sequitur: Means “it doesn’t follow”; the writer’s conclusion is not necessarily a logical result of the facts. • Begging the question: The writer presents as truth what is supposed to be proven by the argument. • Red herring: The writer introduces an irrelevant point to divert the readers’ attention from the main issue. 16 The Logical Appeal Common Fallacies • Post hoc, ergo propter hoc: Means “after this, therefore because of this”; writer assumes that because one event follows another in time, the first event caused the second. • Ad hominem: Means “to the man”; the writer attacks the opponent’s character rather than the argument. • Ad populum: Means “to the people”; the writer evades the issues by appealing to readers’ emotional reactions to certain subjects. • Circular reasoning: The writer uses statements that restate what is already implied; the “evidence” being used is actually a restatement of the problem. 17 The Logical Appeal Common Fallacies • Card stacking: Using only evidence to support one opinion or side and ignoring other perspectives. • Quick Fix: The writer relies on catchy phrases or slogans that may not hold up under cross- examination. • Either/Or: The writer tries to convince the readers that there are only two sides to an issue—one right and one wrong. • Faulty use of authority: The writer relies on testimony from an “expert” speaking about something that is not from his/her field of expertise. 18 The Logical Appeal Methods of “Arguing” Adapted from Weston, Anthony. A Rulebook for Arguments. 3rd ed. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 2000. Arguments are constructed through logical reasoning, the process by which premises are connected/related to construct an argument. Arguments identify major perspectives and viewpoints, then collect evidence to support and/or refute those viewpoints in an effort to reach the best possible conclusion. Common fallacies: hasty generalization, quick fix, either/or 19 The Logical Appeal Methods of “Arguing” By Example: offer examples to support generalizations • Use multiple, representative examples • Provide background information • Test using counterexamples Common rhetorical strategies: narration, description, illustration, definition Common fallacies: card stacking, begging the question, circular thinking 20 The Logical Appeal Methods of “Arguing” By Analogy: use an extended comparison emphasizing points of similarity • Pick analogous example based on points of similarity • Insure analogy is relevant to conclusions Common rhetorical strategies: comparison/contrast, classification/division Common fallacies: faulty analogy, non sequitur, either/or 21 The Logical Appeal Methods of “Arguing” By Authority: incorporate information from sources to support conclusions • Cite sources completely and correctly. • Seek informed, credible, impartial sources. • Verify information from sources. Common rhetorical strategies: illustration, definition Common fallacies: faulty use of authority, ad hominem, red herring 22 The Logical Appeal Methods of “Arguing” By Causes: look for causal relationships in correlations • Explain how cause leads to effect; identify direction of causality • Propose most likely cause; recognize causes may be complex • Recognize correlated events may be coincidental or have common causes Common rhetorical strategies: process analysis, causal analysis Common fallacies: post hoc, non sequitur 23 The Logical Appeal Methods of “Arguing” By Deduction: derive conclusions from relevant generalizations/premises • Verify that individual premises are true • Verify that form is logical and valid Common rhetorical strategies: illustration, definition Common fallacies: non sequitur, begging the question, circular reasoning 24 The Emotional Appeal Appealing to the Heart We think with our heads, but we act with our hearts. If you want your audience to do something, make them feel something first. Propaganda is a means of “propagating,” or spreading, ideas to a large audience. Most propaganda uses emotional appeals to encourage an audience to think or act in a certain way. Common fallacies: card stacking, hasty generalization 25 The Emotional Appeal Propaganda Methods 1. Bandwagon: “Everyone else is doing it/believing it/thinking it, so you should, too!” • Common fallacy:ad populum 2. Testimonial: Using people (often famous) to endorse a product or idea to show why it is the best choice. • Common fallacy: faulty use of authority 3. Loaded Language: Using specific language that taps into particular human feelings. • Common fallacies: quick fix, red herring 26 The Emotional Appeal Propaganda Methods 4. Glittering generalities: Using non-specific superlatives to make a product or idea seem particularly special. • Common fallacies: quick fix, hasty generalization 5. Name calling: Pegging or pigeonholing people or ideas using names or stereotypes. • Common fallacy: ad hominem 6. Association: Connecting an idea with a particular group of people/attitude (plain folks or snob appeal) • Common fallacies: begging the question, ad populum 27 The Ethical Appeal A Question of Values • VALUES are what we hold to be important. These are based on our MORALS, beliefs we use to identify good and bad and distinguish between right and wrong. ETHICS is the process by which we apply our values to make CHOICES when values come into CONFLICT. It is not a question of legality or morality, but the careful consideration of options based on what we hold to be important. 28 The Ethical Appeal Know Your Audience Who is your audience? What do they value? Why do they hold these values? How do they see the issue you are presenting? • Commonplace: Values or beliefs shared by the audience, the starting point of effective argument. • Framing: Defining the parameters of an issue so your audience sees it your way. • Redefinition: Giving a “new” meaning to an “old” idea in order to change your audience’s perspective. Heinrichs, Jay. Thank You For Arguing. New York: Three Rivers Press, 2007. 29 The Ethical Appeal Know How They See You How does your audience relate to you? How have you established rapport with them? Why should they “believe in you”? • Reputation: How your audience judges your character. Are you credible, trustworthy, and transparent? • Decorum: Latin “fit” or “suitable.” Do you meet your audience’s expectations? Heinrichs, Jay. Thank You For Arguing. New York: Three Rivers Press, 2007. 30