The Political Economy of Liberal Democracy

advertisement

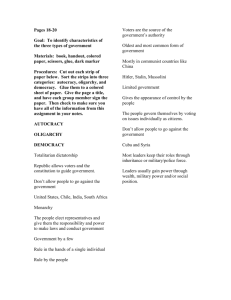

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF LIBERAL DEMOCRACY Dani Rodrik December 2015 Based on: “The Political Economy of Liberal Democracy,” NBER Working Paper No. 21540, September 2015 (with Sharun Mukand) Democracy has won – but what kind of democracy? Figure 1: Numbers of democracies and non-democracies since 1800 Data are from Polity IV (http://www.systemicpeace.org/inscrdata.html). “Democracies” are countries that receive a score of 7 or higher in the Polity’s democ indicator (which takes values between 0 and 10), while “non-democracies” are countries with a score below 7. .4 .6 .8 1 1.2 1.4 Distribution of electoral and civil rights 0 .2 .4 .6 .8 1 x electoral_rights civil_rights Source: Based on Freedom House raw scores for 196 countries. “Electoral rights” refer to free and fair elections (A1+A2); “civil rights” combine measures of independent judiciary (F1), rule of law (F2), and equal treatment (F4). Distribution of electoral and civil rights .4 .6 .8 1 1.2 1.4 modal electoral rights are quite high, while modal civil rights are on the low side 0 .2 .4 .6 .8 1 x electoral_rights civil_rights Source: Based on Freedom House raw scores for 196 countries. “Electoral rights” refer to free and fair elections (A1+A2); “civil rights” combine measures of independent judiciary (F1), rule of law (F2), and equal treatment (F4). What we do • provide an analytical taxonomy of political regimes • distinguishing, in particular, between “liberal” and “electoral democracy” • propose a particular approach to modeling liberal politics • focusing on absence of discrimination in provision of public goods, broadly construed • examine, formally, circumstances under which LDs might emerge • emphasizing the role of income and identity cleavages • relate theoretical findings to empirical cases Three sets of rights • Property rights protect asset holders and investors against expropriation by the state or other groups. • Political rights guarantee free and fair electoral contests and allow the winners of such contests to determine policy subject to the constraints established by other rights (when provided). • Civil rights ensure equality before the law – i.e. nondiscrimination in the provision of public goods such as justice, security, education and health. Electoral versus Liberal Democracy • ED = property rights + political rights • LD = ED + civil rights A taxonomy of political regimes property rights no no civil rights yes no yes political rights political rights yes no Yes A taxonomy of political regimes property rights no no yes political rights political rights yes no Yes no (5) right-wing autocracy (6) electoral/illiberal democracy yes (7) liberal autocracy (8) liberal democracy civil rights A taxonomy of political regimes: illustrations property rights no no yes political rights political rights yes no Yes no (5) right-wing autocracy (6) electoral/illiberal democracy Argentina, Croatia, Turkey, Ukraine,… (n=45) yes (7) liberal autocracy Monaco (n=1) (8) liberal democracy Canada, Chile, S. Korea, Uruguay,… (n=46) civil rights Source: Based on Freedom House raw scores for 196 countries. The cutoff for electoral and liberal democracies is 0.8 on a [0,1] scale of electoral and civil rights as defined earlier. “Electoral rights” refer to free and fair elections (A1+A2); “civil rights” combine measures of independent judiciary (F1), rule of law (F2), and equal treatment (F4). A taxonomy of political regimes property rights no yes political rights political rights no yes no Yes no (1) personal dictatorship or anarchy (2) dictatorship of the proletariat (5) right-wing autocracy (6) electoral/illiberal democracy yes (3) n.a. (4) democratic communism (7) liberal autocracy (8) liberal democracy civil rights Three groups in society • A propertied elite, whose primary objective is to keep and accumulate their assets (property rights); • A majority, who want electoral power so they can choose policies that improve their economic conditions (political rights); • A minority (ethnic, linguistic, regional, ideological), who desire equality under the law and the right not to be discriminated against in jobs, education, etc. (civil rights). Note the two cleavages; • the income/class cleavage • the “identity” cleavage (elite versus non-elite) (majority versus minority) An immediate result • LD is an unlikely outcome of any “democratic settlement” between the elite (who have the resources) and the majority (who have the numbers) • so what’s surprising is not how rare LD is, but that it exists at all • Why this has been overlooked: • in (formal) political economy: tendency to focus on elite-non-elite cleavage • in history of liberalism: failure to ask why propertied elite should want to protect minority rights in addition to theirs (i.e., property rights), so conflation of property with civil rights When might LD emerge? The exceptions that prove the rule • Weak or non-existent identity cleavages • Japan or South Korea (after late 1980s) • Elite shares identity with minority • South Africa (after 1994) • Multiple identity cleavages • Lebanon (until 1975) • More can be said using explicit formal structure • Main result: LD requires both moderate income inequality and weak identity cleavage More formal structure (1) • members of each group 𝑖 ∈ 𝑒, 𝑎, 𝑏 derive utility from their (after-tax) income 𝑦𝑖 and from consuming a public good 𝜋𝑖 . 𝑢𝑖 = 𝑦𝑖 + 𝜋𝑖 . • pre-tax/transfer shares of the elite and non-elite given by 𝛼 and (1-𝛼), respectively. • elite constitute a negligible share of the population but control more 1 than half of pre-tax/transfer output (𝛼 > ). 2 • non-elite are split between a majority and a minority, with population 1 2 shares n and (1-n), respectively (n > ). • gap between 𝛼 and 1 2 is a measure of the class (income) cleavage. More formal structure (2) • we model the identity cleavage by assuming groups exhibit differences in the type of public good they prefer. • type of public goods is indexed by 𝜃 ∈ 0,1 • three groups’ ideal types are given by 𝜃𝑖 , 𝑖 ∈ 𝑒, 𝑎, 𝑏 • the deadweight loss associated with the provision of public goods increases with the level of expenditures and the gap (from the perspective of each group) between the type that is provided and the preferred type. • denoting total expenditure on the public good by 𝑟, the utility derived from the public good is thus expressed as 𝜋𝑖 = 𝑟 − 1 + 𝜃𝑖 − 𝜃 𝛾 2 𝑟 2 • we normalize the majority’s preferred public good by taking 𝜃𝑎 = 1. More formal structure (3) • the political regime determines (i) how the public good is financed (whether through general taxation or the extraction of a surplus from the non-elite), (ii) the level of expenditures on the public good, and (iii) the type of public good provided. • in right-wing autocracy (RA), the elite make all these decisions • in liberal autocracy (LA), the elite remain in the driving seat, but they cannot discriminate against any particular group in taxation or the nature of public good • in electoral democracy (ED), the majority selects an economy-wide tax rate and chooses the type of public good, disregarding the minority’s wishes completely. • in liberal democracy (LD), the majority retains control over the tax rate, but they cannot discriminate against the minority. • so they must provide a public good which lies somewhere in between the majority and minority’s ideal types Taxes and public goods in different political regimes political rights no civil rights yes no yes (5) right-wing autocracy (RA) (6) electoral democracy (ED) 𝜎 𝑅𝐴 = 1 𝛾(1 − 𝛼) 𝜏 𝐸𝐷 = 𝛼 𝛾 𝜃 = 𝜃𝑒 𝜃 = 𝜃𝑎 = 1 (7) liberal autocracy (LA) (8) liberal democracy (LD) 𝑡 𝐿𝐴 1−𝛼 = 𝛾 𝜃 = 𝜃, with 𝜃𝑏 < 𝜃 < 1 𝜏 𝐿𝐷 𝛼 = 𝛾(2 − 𝜃) 𝜃 = 𝜃, with 𝜃𝑏 < 𝜃 < 1 ED versus LD: nature of public goods political rights no civil rights yes no yes (5) right-wing autocracy (RA) (6) electoral democracy (ED) 𝜎 𝑅𝐴 = 1 𝛾(1 − 𝛼) 𝜏 𝐸𝐷 = 𝛼 𝛾 𝜃 = 𝜃𝑒 𝜃 = 𝜃𝑎 = 1 (7) liberal autocracy (LA) (8) liberal democracy (LD) 𝑡 𝐿𝐴 1−𝛼 = 𝛾 𝜃 = 𝜃, with 𝜃𝑏 < 𝜃 < 1 𝜏 𝐿𝐷 𝛼 = 𝛾(2 − 𝜃) 𝜃 = 𝜃, with 𝜃𝑏 < 𝜃 < 1 ED versus LD: taxes political rights no civil rights yes no yes (5) right-wing autocracy (RA) (6) electoral democracy (ED) 𝜎 𝑅𝐴 = 1 𝛾(1 − 𝛼) 𝜏 𝐸𝐷 = 𝛼 𝛾 𝜃 = 𝜃𝑒 𝜃 = 𝜃𝑎 = 1 (7) liberal autocracy (LA) (8) liberal democracy (LD) 𝑡 𝐿𝐴 1−𝛼 = 𝛾 𝜃 = 𝜃, with 𝜃𝑏 < 𝜃 < 1 𝜏 𝐸𝐷 ≥ 𝜏 𝐿𝐷 since 𝜃 ≤ 1 𝜏 𝐿𝐷 𝛼 = 𝛾(2 − 𝜃) 𝜃 = 𝜃, with 𝜃𝑏 < 𝜃 < 1 Payoffs to groups in different political regimes political rights no yes (5) right-wing autocracy (RA) (6) electoral democracy (ED) 𝑢𝑒 = 𝛼 + no civil rights 1 2𝛾 𝑢𝑎 = 1 − 𝛼 − 1 𝛾 𝑢𝑎 = 1 − 𝛼 𝑢𝑏 = 1 − 𝛼 − 1 𝛾 𝑢𝑏 = 1 − 𝛼 + (7) liberal autocracy (LA) 𝑢𝑒 = 𝛼 + yes 𝛼 𝜃 + 𝑒 𝛼2 𝛾 2𝛾 1 + 𝛼2 2𝛾 𝑢𝑒 = 𝛼 − 2𝛼 − 1 𝜃𝑏 2 𝛼 2𝛾 (8) liberal democracy (LD) 1−𝛼 2 2𝛾 𝑢𝑒 = 𝛼 − 1−𝛼 2𝛾 1−𝛼 1−𝛼 2𝛾 𝑢𝑎 = 1 − 𝛼 + 3𝛼 − 1 − 1 − 𝜃𝑒 1 − 𝛼 𝑢𝑏 = 1 − 𝛼 + 3𝛼 − 1 − 𝜃𝑏 − 𝜃𝑒 2𝛼−1 𝛼 (2−𝜃) 𝛾 + 𝑢𝑎 = 1 − 𝛼 + 𝑢𝑏 = 1 − 𝛼 + 3−2𝜃− 𝜃𝑒 −𝜃 2𝛾(2−𝜃)2 1 𝛼2 2𝛾(2−𝜃) 𝛼2 3 − 3𝜃 + 𝜃𝑏 1 𝛼2 2−𝜃 2𝛾(2 − 𝜃) Payoffs to groups in LD versus ED • Majority: • Minority: • Elite: 𝑢𝑎𝐿𝐷 < 𝑢𝑎𝐸𝐷 𝑢𝑏𝐿𝐷 > 𝑢𝑏𝐸𝐷 𝑢𝑒𝐿𝐷 > 𝑢𝑒𝐸𝐷 𝑢𝑒𝐿𝐷 < 𝑢𝑒𝐸𝐷 (unambiguous) (unambiguous) if elites share identity with minority (e.g., 𝜃𝑒 ≈ 0) if elites share identity with majority (𝜃𝑒 ≈ 1) and income/class cleavage not too deep (12 < 𝛼 < 23) A specific game • status quo: Right-wing Autocracy (RA) • shock makes RA unsustainable, in the sense that expected utility to majority from revolution exceeds utility under RA, i.e. 𝑢𝑎𝑅𝐴 = 𝑢𝑏𝑅𝐴 < 𝜌𝑢𝑎𝐷𝑃 = 𝜌𝑢𝑏𝐷𝑃 [𝜌 is probability revolution succeeds; otherwise majority gets payoff of 0] • elite move first and offer a regime in the set LA, ED, LD • majority move next, and they either accept the regime offered, or they mount a revolution • finally, minority move last, and they decide either to join the revolution or to stay put Results • The parameter space under which ED emerges is larger than (and encompasses) the parameter space under which LD emerges. • Proposition 1. There exist parameter combinations under which ED will emerge and LD will not. The reverse is not true. • Under the specific parameterization in the paper: • Proposition 2. The equilibrium configuration of the political regimes is as follows: when 𝛼 ≤ 𝛼𝑎𝑚𝑖𝑛 , the elite offer LA and the majority accepts it; ii. when 𝛼𝑎𝑚𝑖𝑛 < 𝛼 ≤ 𝛼𝑎𝑖𝑛𝑡 , the elite offer LD and the majority accepts it; iii. when 𝛼𝑎𝑖𝑛𝑡 < 𝛼 ≤ 𝛼𝑎𝑚𝑎𝑥 , the elite offer ED and the majority accepts it; iv. when 𝛼 > 𝛼𝑎𝑚𝑎𝑥 , the majority mount a revolution regardless of what the elite offer. i. 𝛼𝑎𝑖𝑛𝑡 𝛼𝑎𝑚𝑎𝑥 𝛼𝑎𝑚𝑖𝑛 Note: the greater the identity cleavage (𝜃𝑎 − 𝜃𝑏 ), the larger the difference between 𝛼𝑎𝑖𝑛𝑡 and 𝛼𝑎𝑚𝑎𝑥 Equilibrium regimes 𝛼𝑎𝑖𝑛𝑡 𝛼𝑎𝑚𝑖𝑛 𝛼𝑎𝑚𝑎𝑥 Equilibrium regimes 𝛼𝑎𝑖𝑛𝑡 𝛼𝑎𝑚𝑖𝑛 LA 𝛼𝑎𝑚𝑎𝑥 Equilibrium regimes 𝛼𝑎𝑖𝑛𝑡 𝛼𝑎𝑚𝑎𝑥 𝛼𝑎𝑚𝑖𝑛 LA Revolution Equilibrium regimes 𝛼𝑎𝑚𝑎𝑥 𝛼𝑎𝑖𝑛𝑡 𝛼𝑎𝑚𝑖𝑛 LA ED Revolution Equilibrium regimes 𝛼𝑎𝑚𝑎𝑥 𝛼𝑎𝑖𝑛𝑡 𝛼𝑎𝑚𝑖𝑛 LA LD ED Revolution Equilibrium regimes 𝛼𝑎𝑚𝑎𝑥 𝛼𝑎𝑖𝑛𝑡 𝛼𝑎𝑚𝑖𝑛 LA LD ED Revolution Note: the emergence of liberal democracy requires both mild inequality (low 𝛼) and the absence of large identity cleavages (proximity between 𝜃𝑎 and 𝜃𝑏 ). Discussion • region in which LD emerges as equilibrium is squeezed from below by the availability of LA (which satisfies the elite’s incentive constraint) and from above by ED (which satisfies the majority’s participation constraint) • Size of LD zone depends on the nature of identity cleavages. i. ii. when the elite share an identity with the minority they would prefer LD to ED for a larger share of the parameter space when the identity cleavage between majority and minority gets smaller, the majority’s preference for ED over LD becomes weaker. The West versus the rest • In the West, liberalism comes before franchise • conflation of property rights with minority rights • extending the franchise is a compromise for liberals • ED arrives when social mobilization is based on class (rather than identity) • In developing countries, bleaker prospects for LD • social mobilization in the context of identity politics (decolonization, wars of secession or national liberation) • ethnic/identity cleavages comparatively strong • delayed industrialization (and premature de-industrialization), so class-based cleavage comparatively weak Final words • Puzzle is not rarity of liberal democracy, but that it exists at all • Endogeneity of cleavages • determined both by structural and ideational factors • Fundamental political difference between income/class versus identity cleavages • both cleavages can serve as basis for majoritarian populism, but populism of the “left” aims to ultimately overcome income cleavage, while populism of the “right” necessarily deepens identity cleavage Additional slides But what kind of democracy? • widespread rights violations • discrimination against minorities and opposition groups in many OECD countries: Hungary, Croatia, Israel, Mexico, Turkey • much worse in countries like Russia and Venezuela • even though elections remain in principle free and competitive • preponderance of intermediate regimes • Fareed Zakaria: “illiberal democracy” • Steve Levitsky and Lucan Way (2010): “competitive authoritarianism” Our treatment of “civil rights” (1) • We model civil rights as the non-discriminatory provision of public goods. • We interpret the relevant public goods broadly, including justice and free-speech rights as well as education, health, and infrastructure. • what sets LD apart from ED is that an elected government cannot discriminate against specific individuals or groups when it administers justice, protects basic rights such as freedom of assembly and free speech, provides for collective security, or distributes economic and social benefits. • Our treatment has the advantage that it provides a tractable approach for modeling LD and distinguishing it from other political regimes. • thinking of liberalism broadly as non-discrimination allows us to sidestep debates about what are the “essential” characteristics of liberalism. • our formulation is flexible enough to encapsulate individual and minority rights • it applies to a variety of different contexts – non-discrimination in the administration of justice, access to education, use of public infrastructure, or right to free speech • furthermore, our emphasis on public goods means that we focus on an outcome that is sufficiently general that it can be applied in different country, cultural and historical contexts. Our treatment of “civil rights” (2) • Our distinction between electoral and liberal democracies relies on the presumption that free and fair elections – the hallmark of electoral democracy – can be separated from equal treatment and nondiscrimination – the hallmarks of liberalism. • It may be difficult at times to disentangle certain civil rights from political rights. In particular, it can be argued that elections cannot be entirely fair when the capacity of citizens to participate and compete in elections is constrained – indirectly – by restrictions on their civil rights. Citizens who are deprived of, say, adequate educational opportunities or the protections of the rule of law cannot be effective participants in electoral contests. • But this is a caution about the fuzziness in practice between electoral and liberal democracies, rather than an objection that renders our distinction between the two regimes entirely invalid. • To require equality of access across the full range of public goods as a precondition for free and fair elections would also set too high a threshold. A taxonomy of political regimes property rights no yes political rights political rights no yes no (1) personal dictatorship or anarchy (2) dictatorship of the proletariat yes (3) n.a. (4) democratic communism civil rights no Yes What about Liberal Autocracy (LA)? political rights no civil rights yes no yes (5) right-wing autocracy (RA) (6) electoral democracy (ED) 𝜎 𝑅𝐴 = 1 𝛾(1 − 𝛼) 𝜏 𝐸𝐷 = 𝛼 𝛾 𝜃 = 𝜃𝑒 𝜃 = 𝜃𝑎 = 1 (7) liberal autocracy (LA) (8) liberal democracy (LD) 𝑡 𝐿𝐴 1−𝛼 = 𝛾 𝜃 = 𝜃, with 𝜃𝑏 < 𝜃 < 1 𝜏 𝐿𝐷 𝛼 = 𝛾(2 − 𝜃) 𝜃 = 𝜃, with 𝜃𝑏 < 𝜃 < 1 minority could prefer LA to ED due to nature of public good 𝛼𝑏𝑖𝑛𝑡 𝛼𝑏𝑚𝑎𝑥 𝛼𝑏𝑚𝑖𝑛 𝛼𝑒∗