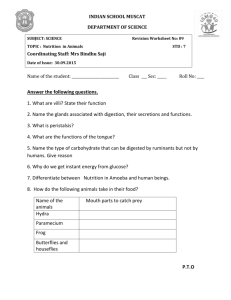

The Recommendation Document: overview

advertisement