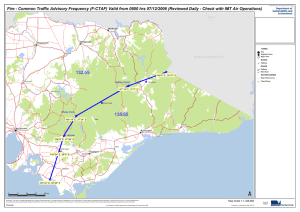

2009 Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission

advertisement