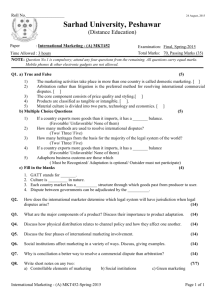

ANATOMY OF INDUSTRIAL CONFLICT

advertisement

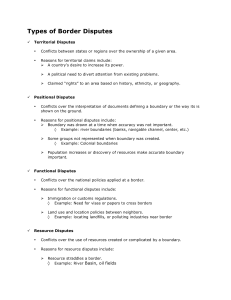

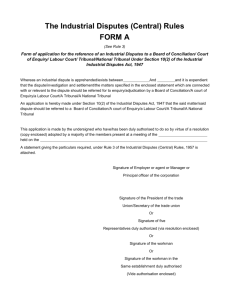

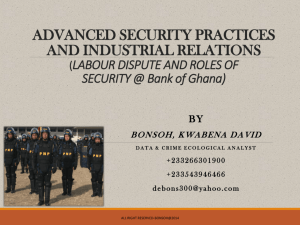

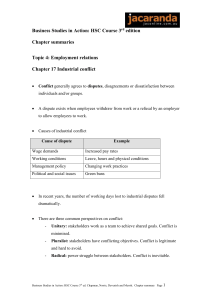

ANATOMY OF INDUSTRIAL CONFLICT Concept and Essentials of a Dispute According to the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947, Section 2(k); “industrial disputes mean any dispute or difference between employers and employers, or between employers and workmen or between workmen and workmen, which is connected with the employment or non-employment or terms of employment or with the conditions of Labour of any person." Contd. For a dispute to become an industrial dispute, it should satisfy the following essentials: 1. There must be a dispute or a difference (a) between employers (such as wagewarfare where labour is scarce); (b) between employers and workmen (such as demarcation disputes): and (c) between workmen and workmen. Contd. 2. 3. 4. It is connected with the employment or nonemployment or the terms of employment or with the conditions of labour of any person (but not with the managers or supervisors), or it must pertain to any industrial matter, A workman does not draw wages exceeding Rs. 1,600 per month. The relationship between the employer and the workman must be in existence and should be the result of a contract and the workman actually employed. Interpretation of disputes by courts Some of the principles for judging the nature of a dispute evolved by the courts are as follows. 1. The dispute must affect a large group of workmen who have a community of interest and the rights of these workmen must be affected as a class. In other words, a considerable section of employees should necessarily make common cause within the general lot. Contd. 2. 3. The dispute should invariably be taken up by the industry union or by an appreciable number of workmen. There must be a concerted demand by the workers for redress and the grievance becomes such that it turns from individual complaint into a general complaint. Contd. 4. The parties to the dispute must have direct and substantial interest in the dispute, i.e., there must be some nexus between the union which espouses the causes of the workmen and the dispute. Moreover, the union must fairly claim a representative character. Contd. 5. If the dispute was in the beginning in an individual's dispute and continued to be such till the date of its reference by the government for adjudication, it cannot be converted into an industrial dispute by support subsequent to the reference even of workmen interested in the dispute. Contd. By incorporating Section 2A in the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947, a right has been given to the individual workman himself to raise an industrial dispute with regard to termination, discharge, dismissal, or retrenchment of his service, even though no other workman or any trade union of workmen raises it or is a party to the dispute. Contd. Patterson observes: "Industrial strikes/disputes constitute militant and organized protests against existing industrial conditions. They are symptoms of a discorded system. The industrial unrest, thus, takes an organized form when the work people make common cause of their grievances against employers by way of strikes, demonstrations, picketing, morchas, gate meetings, gheraos, etc. Classification of Industrial Disputes The most common practice is to make a distinction between two main types of disputes relating to terms of employment. They are: a) disputes that arise out of deadlocks in the negotiations for a collective agreement, popularly known as interest disputes,' and b) disputes that arise from day-to-day workers' grievances or complaints, popularly known as grievance disputes. Contd. In addition, in various countries, special provisions apply to two other types of disputes relating to organisational rights, namely: c) those arising from acts of interference with the exercise of the right to organise, or acts commonly known as unfair labour practices,' and d) disputes over the right of a trade union to represent a particular class or category of workers for purposes of collective bargaining, simply referred to as recognition disputes. Details of Classification a) Interest Disputes: These disputes are also called conflicts of interest or economic disputes. They generally correspond to what in some countries are called collective labour disputes. In general, they relate to the determination of new terms and conditions of employment for the general body of workers. In most cases, the disputes originate from trade union demands or proposals for improvements in wages, fringe benefits, job security, or other terms or conditions of employment. Contd. These demands or proposals are normally made with a view to conclude a collective agreement. Since there are generally no mutually binding standards that can be relied upon to arrive at a settlement of interest disputes, recourse must be made to bargaining power, compromise, and sometimes, a test of economic strength before the parties reach an agreed solution. As the issues in these disputes are "compromisable" they lend themselves best to conciliation, and are a matter of give-and-take and bargaining between the parties. Contd. b) Grievance or Rights Disputes: These disputes are also known as conflicts of rights or legal disputes. They involve individual workers only or a group of workers in the same group and correspond largely to what in some countries are called individual disputes. They generally arise from day-to-day working relations in the undertaking, usually as a protest by the worker or workers concerned against an act of management that is considered to violate their rights. Contd. The grievances typically arise on such questions as discipline and dismissal, the payment of wages and other fringe benefits, working time, over-time, time-off entitlements, promotion, demotion, transfer rights of seniority, rights of supervisors and union officials, job classification problems, the relationship of work rules to the collective agreement and the fulfillment of obligations relating to safety and health laid down in the agreement. Contd. In some countries, grievances arise especially over the interpretation and application of collective agreements. The grievance disputes are, therefore, also called interpretation disputes. Such grievances, if not dealt with in accordance with a procedure that is respected by the parties, often result in· embitterment of the working relationship and a climate of industrial strife. Contd. There is a definite standard for setting a grievance dispute - the relevant provision of the collective agreement, employment contract, works rules or law, or custom or usage. In many countries, Labour Courts or Tribunals adjudicate over grievance disputes. In other words, government encourages voluntary arbitration for their settlement. Contd. c) Disputes Over Unfair Labour Practices: The most common unfair labour practices in industrial relations parlance are attempts by the management of an undertaking to discriminate against workers on the ground that they are trade union members or participate in trade union activity. In most cases, the objects of this discriminatory treatment are union officials or representatives employed in the undertaking, and trade union members who have actively participated in strikes. Contd. Other unfair labour practices are generally concerned with interference, restraint or coercion of employees when they exercise their right to organise, join or assist a union, establishment of employer-sponsored unions, refusal to bargain collectively, in good faith, with the recognized union; recruiting new employees during a strike which is not an illegal strike; failure to implement an award, settlement or agreement; indulging in acts of force or violence, etc. Contd. These unfair labour practices are also known in various countries as trade union victimisation. In many countries, a special procedure exists under the law for the prevention of such practices. Such a procedure obviates or precludes conciliation. In the absence of such procedure, disputes are settled according to the normal procedure laid down under the Disputes Act. Contd. d) Recognition Disputes: This type of dispute arises when the management of an undertaking or employer's organisation refuses to recognise a trade union for the purpose of collective bargaining. Contd. Issues in recognition disputes differ according to the cause which has led the management to refuse recognition. It may be that the management dislikes trade unions and will not have anything to do with a trade union; the problem is then of attitude, as in the case of trade union victimisation. However, the management's refusal may be on the ground that the union requesting recognition is not sufficiently representative, or that there are several unions in the undertaking making conflicting claims to recognition. Contd. In such a case, the resolution of the issue may depend on the existence or non-existence of rules for determining the representative character of a trade union for the purpose of collective bargaining. Such rules need not necessarily be laid down by law; they may be conventional or derived from prevailing practices in the country. In many countries, guidelines for trade union recognition have been laid down in voluntary Codes of Discipline or Industrial Relations Charters accepted by employers' and workers' organisations. Impact of Industrial Disputes The consequences of industrial disputes are very far-reaching, for they disturb the economic, social and political life of a country. The workers, the employers, the consumers, the community and the nation suffer in more than one way. Various impacts 1. Industrial disputes result in a huge wastage of mandays and dislocation in the production work. A strike in a public utility service disorganizes public life and throws the economy out of gear; and consumers are subjected to untold hardships. the short supply of consumer goods results in sky-rocketing prices, and leads to their non-availability in the open market. The workers are also badly affected in more than one ways. Contd. 2. The employers suffer heavy losses, not only through stoppages of production, reduction in sales and loss of markets but also in the form of huge expenditure incurred on crushing strikes, engaging strike-breakers and blacklegs maintaining a police force and guards; Apart from these losses, the loss of mental peace, respect and status in society cannot be computed not in terms of money. Contd. 3. The public/society, too, is not spared, industrial unrest creates law and order problems, necessitating increased vigilance on the part of the state. Further, even when disputes are settled, strife and bitterness continue to linger, endangering social relations. Contd. 4. Industrial disputes also affect the national economy. Prof. Pigou has observed: When labour and equipment in the whole or any part of an industry are rendered idle by a strike or lockout, national dividend must suffer in a way that injures economic welfare .... It may happen in two ways. Contd. On the one hand, it impoverishes the people actually involved in the stoppage, it lessens the demand for the goods the other industries make; on the other hand, if the industry in which the stoppage has occurred is one that furnishes a commodity or service largely used in the conduct of other industries, it lessens the supply to them of raw material or equipment for their work. This results in a loss of output, ultimately reducing the national income. Hence developmental activities cannot be undertaken for want of necessary finances.