Interdependence between Islamic capital market and money market

Interdependence between Islamic capital market and money market: Evidence from Indonesia

Gandhi Anwar Sani a1

and Imam Wahyudi b2 a

Inspectorate General, Ministry of Finance Republic of Indonesia

,b

Department of Management, Faculty of Economic, University of Indonesia

Abstract

This study investigate VAR Toda-Yamamoto causality test between macroeconomic variables and Islamic financial market. The purpose of this study is to analyze the information content of Islamic capital market and Islamic money market return with respect to several macroeconomic indicators. Using bivariate method, we found that Islamic capital market index (JII) has more content information than Islamic money market index (SBIS). The exchange rate and interest rate (SBI) significantly affected JII. Otherwise, none of the macroeconomic variables found to significantly affect SBIS. Using multivariate method,

SBIS has more content information (SBI, industry production index, and inflation rate) than

JII (exchange rate). Contradiction in these findings indicates the presence of (i) interaction between the macroeconomic variables, (ii) interaction between the financial market and the macroeconomic variables, and (iii) interaction between the Islamic capital market and money market. Further, by considering these interactions, SBIS tends to have more information contents than JII, thus more suitable for use as a barometer of monetary policies in Indonesia.

Key words : Islamic finance, capital market, money market, monetary, causality.

1. Introduction

In financial theory, the performance of money markets and stock markets are supposed to be negatively correlated (Friedman, 1988). An increase in the interest rate will be followed by increase in the opportunity cost of the cash holding, and it will trigger the substitution effect

1 Correspondence address: Juanda II Building, floor 5, Inspectorate General, Ministry of Finance Republic of

Indonesia, telp. (+628159792633); email: gandhianwar@depkeu.go.id

or gandhianwar@gmail.com

.

2 Correspondence address: Department of Management Building, floor 2, Faculty of Economics, University of

Indonesia, telp. (+6221 7272425); fax. (+6221 7863556); email: i_wahyu@ui.ac.id.

This paper was also presented at The 15th Malaysian Finance Association Conference on June 2013 .

1

on stocks and other interest bearing securities. At the same time, the increase of interest rate in the market will increase the discount rate in the valuation model as reflected on the nominal risk-free rate, therefore leads to an inverse relationship between interest rates and stock prices (Maysami and Koh, 2000). The change of interest rate is positively correlated with the growth in money supply and expansion of the real sector (Mishkin, 2004), and it leads to an increase in the firm’s cash flows and stock price, but when the level of increase in the cash flow is not same with the increase in discount rate as well as in the nominal risk-free rate (DeFina, 1991), the increase in the discount rate will decrease the stock price (Maysami and Koh, 2000). This relationship emerged as the result of the application of interest rate regimes. On the other side, when the uncertainty of returns on equity is high and resulted in lower stock market performance, investors immediately shift their funds to money markets through investments in fixed income instruments. It is natural to assume that investing in money markets is much safer than investing in stock markets, when the market is volatile.

Both money markets and stock markets are believed to play an important role in transmitting monetary and fiscal policies in a country.

The main actors in money markets are banks, in which they can act as an issuer of financial instruments, the buyer or the seller. Before 1992, only conventional banks existed in

Indonesian banking industry. But since 1992, Islamic banks have emerged into the

Indonesian banking system and the regime of dual monetary systems began to apply. Unlike conventional banks, Islamic bank’s fundamental idea is to abolish the system of interest and to apply the system of profit-loss sharing. In the profit-loss sharing system, the return is calculated based on the real income of the clients’. In this system, the growth of circulated money in the economy should follow the growth of the output occurring. Thus, in the area where the dominant actor is Islamic banks, it is expected that the money market should have independent performance over the movements in market interest rates. The dual monetary system implies that Bank Indonesia as the regulator are responsible to manage the dual monetary policies; the conventional monetary policies through Bank Indonesia Certificates

(SBI) and the Islamic monetary policies through Bank Indonesia Sharia Certificates (SBIS), all at once (Ascarya, 2012).

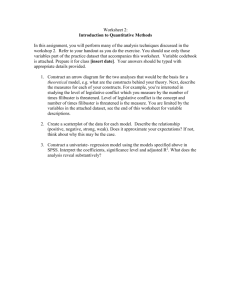

Since 2000, JII has been established as a reference to the performance of Islamic stocks in the Indonesian capital market and should be established based on the principles of

Islamic finance. However, in practice, both returns are indicated to be driven by the same factors, namely SBI rate (see Figure 1 ).

In fact, SBI rate is a form of interest rate, and as such also usury, which is explicitly excluded from any Islamic financial system. Thus both the

2

returns of JII and SBIS should be independent from the movement of SBI’s return. Moreover,

JII and SBIS should reflect the principles of profit-loss sharing based on actual returns on the real sector. Therefore, JII and SBIS should be more influenced by macroeconomic factors than the SBI rate. To prove this, we will examine the relationship between macroeconomic variables and returns of JII and SBIS. Then, to see the effectiveness of the use of either JII or

SBIS as an indicator of the success of the central bank's monetary policy, we will examine both factor to see which of the two has more information content.

The rest of this paper will be arranged as follows. Section 2 is the institutional background and literature review. Section 3 consists of a conceptual framework. Section 4 is the data. Section 5 is the methodology. Section 6 is an analysis of the results. Section 7 is the conclusion and managerial implications.

2. Institutional background and literature review

2.1 Indonesian Islamic stock market

Islamic capital market, as a part of Islamic economic system, serves to increase efficiency in the management of resources and capital, as well as to support investment activities (Ali,

2005). The products and activities of capital markets should reflect the principles of Islam, based on the principles of trust, and the presence of real assets or activities as an underlying object. In addition, transactions in the capital market should be managed in a fair and equitable distribution of benefits. Prohibition of riba , gharar , maysir , tadlis and ikraha in all activities related to muamalah is the fundamental principle supported by some other principles, namely the principle of risk sharing, prohibition of speculative behavior, protection of property rights, transparency, and fairness in agreement contracts (Iqbal and

Tsubota, 2006). Some fundamental differences between conventional and sharia capital markets are shown in Table 1 .

Table 1 Differences between investment in Islamic capital markets and conventional capital markets

No. Islamic Conventional

1 Limited to sectors not prohibited/ included in negative lists of sharia investment and not on the basis of debt (debt-bearing investment)

2 Based on sharia principles that encourage the application of profit-loss sharing partnership schemes

3 Prohibiting various forms of interest, speculation, and gambling

Free to choose either the debt-bearing investment or the profit-bearing investment across sectors

Based on the principle of interest

Allowing speculation and gambling which in turn will lead to uncontrolled market fluctuations

3

No. Islamic Conventional

4 The existence of sharia guidelines governing various aspects such as asset allocation, investment practices, trade and income distribution

5 There is a screening mechanism of companies which must follow sharia principles

Investment guidelines in general in capital market legal products

-

Performance of Islamic stock markets in Indonesia is measured by the Jakarta Islamic

Index (JII). JII was established on the 2 nd of July 2000 and consisted of 30 stocks based on several criteria established by the Capital Market Supervisory Agency and Financial

Institution ( Bapepam & LK ) in accordance with the Decree of the Head of Bapepam & LK

Number: KEP-181/BL/2009 on the Issuance of Sharia Securities which then was amended by the Decree of the Head of Bapepam & LK Number: KEP-208/BL/2012 on Criteria and

Issuance of Sharia Securities Lists. Additionally since 2003, the National Sharia Board

(DSN), MUI has issued Fatwa Number: 40/DSN-MUI/X/2003 on Capital Markets and

General Guidelines for the Implementation of Sharia Principles in the Capital Market.

Issuers/Public Companies shall meet the qualitative and quantitative criteria in order that their stocks can be classified in the JII group. a.

Qualitative criteria, issuers/public companies do not conduct business activities in the field of gambling and games classifies as gambling; trade banned according to sharia; usury financial services; trading risks containing gharar and maysir ; producing, distributing, trading, and/or providing forbidden ( haram ) goods or services; b.

Quantitative criteria, the total interest-based debt is compared to the total assets which are not more than 45%, or the total interest income and the other forbidden ( haram ) income are compared to the total revenue and other income which is not more than 10%.

JII was established in order to serve as a benchmark for the performance of investments in Islamic stocks. In addition, it is expected to increase investors’ confidence in developing Islamic equity investments. Based on the data from Bapepam & LK (now the

Financial Services Authority), the performance of Islamic stocks indices (JII) indicated significant growth. Growth occurred concerning JII monthly closing value of 662.189%, i.e.

70.459 points in January 2002 into 537.031 points in December 2011. Figure 1 shows the value movement of the JII closing index and the SBI and SBIS over the period of 2002-2011.

In 2008 - 2009, JII closing values decreased dramatically, and at the same time there was an increase (although not significant) in the returns of SBI and SBIS. Apparently during this period, the subprime mortgage crisis was occurring in the U.S. This joint incident indicates

4

500

400

300

200

100

0 that the crisis in the U.S. has affected Indonesia through the transmission mechanism in several sectors such as trade, investments, and banking.

Figure 1 Movement of the JII closing index, SBI and SBIS over 2002-2011

(in Rupiah)

600

JII SBI rate SBIS rate

Data sources: JII closing index from Bloomberg; SBI and SBIS from Bank Indonesia. SBI and SBIS are presented in percentage multiplied by 10.

2.2 The theory of market integration

Based on the difficulty and the easiness of capital flows in a country, market integration could be classified into three categories: full integrated markets, mild segmentation and full segmentation (Husnan and Pudjiastuti, 1994; Choi and Rajan, 1997). The more restrictions given by the government, the more it will lead to segmented markets and vice versa. Beckers,

Connor and Curds (1996) defined market integration through three approaches: based on restrictions in investment from international investors, such as regulatory, fiscal (taxes), or administrative impediments; based on the consistency of the stock pricing across capital markets; and based on the correlation between the stock returns across different capital markets.

Armanious (2007) stated that a capital market is considered to be integrated with another capital market if they have an ongoing balance relationship. In other words, there are co-movements among those capital markets indicating the presence of integration among those capital markets. Thus, one capital market can be used as a measuring instrument to

5

predict the return of the other capital market(s). Heaney, Hooper and Jaugietis (2002) considered the integration of regional capital markets as a condition in which investors can buy and sell stocks in any market without any restrictions. Identical securities can be issued, redeemed , and sold in all the markets in the region (Dorodnykh, 2012). This condition implies that identical securities are issued and sold at the same price in any capital market, of course, after adjusting the value to the one of the applicable currency.

2.3 The effects of macroeconomic factors on the financial markets

Macroeconomic represents the interaction among the labor market, the goods market, and the market of economic assets as well as the interaction among countries in the trading activities of one particular country and others (Dornbusch, Fischer, and Startz, 2008). In globalization, the shock occurring within the economy of a given country can lead to contagion effects of the economies of the other countries. When the domestic economy is integrated with the world economy, it becomes vulnerable to any turmoil within the global economy.

In the business scope, macroeconomic factors influence the increase or the decrease in the company's performance, both directly and indirectly. Likewise, Yusof and Abdul Majid

(2007) stated that the conditions of the capital markets as a leading indicator for the economy of a country are intertwined with the country's macroeconomic conditions. In other words, when a country's macroeconomic conditions change, investors calculate their impact on the company’s performance in the future, and then make the decision to buy or sell the stocks they own. This action of stock trading results in the changes of stock price, and ultimately affects the indices in the stock market.

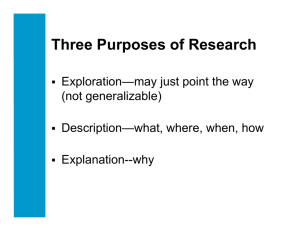

2.4 Transmission of monetary policy in Indonesia

Among the main factors influencing macroeconomic conditions is the monetary policy. To achieve and maintain the stability of the Rupiah by controlling inflations, Bank Indonesia may conduct monetary policy using two financial instruments that have similar functionality, but different in features. The first is Bank Indonesia Certificates (SBI) which belongs to an interest-based instrument. The second is Bank Indonesia Sharia Certificates (SBIS) which is an Islamic-based instrument. The use of SBI and SBIS, as a policy rate , is essential for the

Central Bank as monetary policy makers. With these instruments, Bank Indonesia can influence a bank’s funding and financing behaviour through the interbank money markets, through both the conventional instrument (PUAB) and the Islamic instrument (PUAS), and ultimately affect the cost of the banking funds in distributing credits or financing.

6

Furthermore, the expansion of credits and financing will increase the outputs and affect the rate of inflations (Ascarya, 2012). The chronology of dual monetary policy transmission

(sharia and conventional) in Indonesia can be shown in Figure 2.

In Indonesia, Ningsih (2011) discovered that the transmission route of sharia monetary policy is similar to one of the conventional monetary policy; where PUAS becomes the operational target driven by SBIS in line with Hidayat (2007), where he found that SBI affect SBIS positively. In addition, Wahyudi and Rosmanita (2011) explained that shifts in the convergence trend of SBIS’s returns and SBI’s interest rates were triggered by an attempt of equal treatment made Bank Indonesia over Islamic banks and conventional banks.

Typically, the transmission mechanism of monetary policy through the interest rate channel starts from the short-term interest rates and then spreads to the medium-term interest rates and to the long-term interest rates (Moschitz, 2004).

Figure 2 Transmission route of dual monetary policy running by Bank Indonesia

Monetary policies

SBI

SBIS

PUAB

Transmission in financial sector

Interest rate

Deposits & credits

PUAS

Profit/loss sharing

Deposits & financing

Financial assets price

- bond yield

- sukuk yield

- stock price

- mutual funds

- etc

Transmission in real sector

- real assets price

- property price

- gold price

- others commodity price

- etc

Consumption

Production

Aggregate demand & supply

Output gap

Investment

Inflation &

Rupiah’s stabilization

The transmission mechanism of monetary policy began when Bank Indonesia change its instruments and further affected the operational goals, the intermediate goals and the final goals. Monetary policy transmitted through the interest rate channel can be described in three stages. First is the transmission in the financial sector. Changes in monetary policy through changes in monetary instruments (SBI and SBIS) influence the returns of PUAB (PUAS), deposits and credits (financing), and ultimately affect the price of financial assets (Ascarya,

2012). Second is the transmission from the financial sector to the real sector, in which the impact depends on consumption and investments. The effect of interest rates on consumption

7

occurs through the income effect and the substitution effect. Interest rates will also affect the cost of capital, which in turn will affect investments and production. These effects of the interest rate will have an impact on aggregate demands, and if it is not followed by the aggregate supply, it will cause the output gap and finally affects inflations and the stability of the Rupiah.

Third is the transmission in the real sector through asset prices. Asset prices, as a measure of economic activities, are measured in two ways: wealth effects and yield effects

(Mishkin, 2004). In addition, asset prices also contain information content that can describe the expectations of revenue streams and the direction of inflation in the future. At least there are two theories related to the monetary policy transmission mechanism through asset prices:

Tobin's Q theory of investment and wealth effects of consumption. In Tobin's Q theory, monetary policy is transmitted through the influence of equity assessment. The ratio Q is defined as the market price of the company relative to the replacement cost of capital.

Monetary expansion will increase the firm's stock price expectations, raise the ratio Q, encourage firms to invest, and eventually have an impact on aggregate demands and supplies.

Based on the wealth effects of consumptions, monetary policy will affect consumer-spending decisions. Based on the life cycle hypothesis from Ando and Modigliani (1963), consumption is not constant in the long run given that wealth—measured by financial assets (such as stocks, bonds, and deposits) and real assets (such as gold, properties, and land)—is not constant forever. Monetary expansion will increase the price of financial assets and real assets, causing consumers’ wealth to rise, and it will ultimately increase consumption and aggregate demand.

In addition to transmission through interest rates and asset prices, monetary policy transmission mechanism may take place through the exchange rate channel. Perfect capital mobility will lead to the relationship between short-term interest rates and the exchange rates

(Mundel, 1962). This is called the interest parity relationship, in which differences in interest rates between two countries equal to the expected changes in the exchange rates between the two countries. If the equilibrium has not been reached, capital inflows in the country with high interest rates will continue to happen.

3. Conceptual framework

Research on the relationship among macroeconomic variables, financial markets, and the price of oil has been done for a long time, especially in developed countries such as the U.S.,

8

the U.K., and Japan. Preliminary research on stock market returns by Castanias (1979) and

Hardouvelis (1988) found that economic announcements to be the factor influencing stock market returns. Furthermore, Levine and Zervos (1996), Hooker (2004), as well as Chiarella and Gao (2004) stated that stock market returns are influenced by macroeconomic indicators such as GDP, productivity, and interest rates.

Regarding the relationship between capital market returns and oil price movements,

Sadorsky (1999), Filis (2010) and Degiannakis, Filis and Floros (2013) stated that the determinant factor of the capital market returns is the oil price. Park (2008) found that almost all countries in America and Europe (except for Finland and the UK) empirically indicated that the capital market returns responded significantly to the oil price. In almost all oilimporting countries, shock in oil prices significantly contributed negative to the capital markets. Meanwhile, among the oil-exporting countries, only Norway that showed a significantly positive response to the stock markets over the oil-price shock— where UK was insignificant and Denmark was significantly negative. Furthermore, Park (2008) explained that in the oil-importing countries, changes in the oil price contributed a greater impact on stock market returns than the interest rates.

In the financial markets in Asia, Abdul-Rahman, Sidek and Tafri (2009) examined the interaction of selected macroeconomic variables (i.e., money supply, exchange rates, reserves , interest rates, and the industrial production index) and conventional capital market returns (KLCI) in Malaysia using VAR methodology. They found that there was a cointegration relationship between conventional capital market returns and the rest of the selected macroeconomic variables. Conventional capital market returns were very sensitive to changes in macroeconomic variables. Furthermore, in accordance with the variance decomposition analysis, it was shown that the conventional capital market had a strong dynamic interaction with the reserves and the index of industrial production.

Abdul Majid and Yusof (2009) using the methodology of autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) examined the long-term relationship between the Islamic capital market returns

(KLSI) and selected macroeconomic variables (i.e., money supply, exchange rates, interest rates, the industrial production index, and the Fed rate). They found that the macroeconomic variables that significantly affected the stock price movements belonging to KLSI were exchange rates, money supply, interest rates, and the Fed rate.

Hussin, Razak and Yahya (2012) conducted a study on the relationship between exchange rates, oil prices, and the Islamic capital market (FBMES) in the period of January

2007 – December 2011 in Malaysia by using VAR methodology. They found that the Islamic

9

stock returns had a positive and significant correlation with oil prices, but it had a negative and insignificant relationship with the exchange rate of Malaysian ringgit to the U.S. dollar.

Furthermore, through the test of Granger causality, it was found that oil prices could predict short-term sharia stock returns. However, regarding the exchange rate of Malaysian ringgit to the U.S. dollar, both for short terms and long terms, there was insufficient evidence to be able to predict the movement of sharia stocks in Malaysia.

Based on the empirical findings from previous studies, we formulate the conceptual framework of this research in to build the model and the analysis as follows.

Figure 3 Conceptual framework

Production

Index

Output Gap

Domestic

Inflation

Pressure

Outstanding

Money

Exchange

Rate

Foreign

Inflation

Pressure

Inflation

SBI Rate

Expected

Return

Oil Price The Fed

Return of SBIS

Stock Price

JII

4. Data

This study uses monthly macroeconomic data over the periods of January 2002 – December

2011. Indonesia's macroeconomic data used consists of money supply (M2), Rupiah exchange rates against USD (ER), SBI rate (rSBI), Industrial Production Index (IPI), and inflations (INF). Whereas, the global macroeconomic data consists of the world oil price

(OP) and the Fed rate (FRR). The data on sharia financial markets used in this study are the closing value of the Jakarta Islamic Index (JII) and the return of SBIS (rSBIS).

5. Methodology

5.1 The causality test of Toda-Yamamoto (1995)

In the Granger causality test, to predict the time interval at the co-integrated variables will result in spurious regression, in addition, F-test becomes invalid unless the variables are co-

10

integrated (Shirazi and Abdul Manap, 2005; Akçay, 2011). Although these problems can be solved through the method of error correction model (Engle and Granger, 1987) and vector autoregressive error correction model (Johansen and Julius, 1990; Johansen, 1991), but these approaches are considered not practical and sensitive to the value of the parameters in a limited number of samples and the results are unreliable (Zapata and Rambaldi, 1997).

Toda-Yamamoto (1995) developed Granger causality test procedures to estimate the augmented VAR with the asymptotic distribution of the statistic MWald. These procedures can be done when there is co-integration within the models. Büyükşalvarci and Abdioğlu

(2010) said that the methods developed by Toda-Yamamoto (1995) can be used to find the long-term causality among unintegrated variables in the same order. In addition, the causality test procedures of Toda-Yamamoto (1995) make the Granger causality test easier, and do not require the existence of co-integration testing or the transformation of VAR into VECM.

5.2 VAR Toda-Yamamoto bivariate model

Bivariate models are used to test the causality of each financial market variables (JII and rSBIS) with each macroeconomic variable in turn. The equation of Toda-Yamamoto bivariate model is: lnJII t

= 𝛽

0

+ ∑ 𝐾 𝑘=1 𝛽 k lnJII 𝑡−𝑘

+ ∑ 𝑑1max 𝑑1=1 𝛽

K+d1 lnJII 𝑡−𝐾−𝑑1

+ ∑ 𝑁 𝑛=0 𝛿 n rSBIS 𝑡−𝑛

+

∑ 𝑑2max 𝑑2=1 𝛿

𝑁+𝑑2 rSBIS 𝑡−𝑁−𝑑2

+ 𝜏

1

𝑋 𝑖𝑡

+ 𝜀 𝑡

.

rSBIS t

= 𝜃

0

+ ∑ 𝐾 𝑘=1 𝜃 k rSBIS 𝑡−𝑘

+ ∑ 𝑑1max 𝑑1=1 𝜃

K+d1 rSBIS 𝑡−𝐾−𝑑1

+ ∑ 𝑁 𝑛=0

π n lnJII 𝑡−𝑛

+

∑ 𝑑2max 𝑑2=1

π

𝑁+𝑑2 lnJII 𝑡−𝑁−𝑑2

+ 𝜑

1

𝑋 𝑖𝑡

+ 𝜐 𝑡

.

where: k and n are the lagged period in VAR model; d1max and d2max are the integration’s order of time series data obtained using stationarity test procedures; X j

is is the macroeconomic variable where i = lnM2, lnER, rSBI, IPI, INF, FFR or lnOP; β

0

and θ

0

are the constant; β k

, δ n

, τ

1

, θ k

, π n

and φ

1

are the coefficient of variables; ε t

and υ t

are the white noise disturbance term that assumed that E(ε t

) or E(υ t

) = 0, and E(ε t

υ t

) = 0.

5.3 VAR Toda-Yamamoto multivariate model

Multivariate models are used to test the causality of financial market variables (JII and rSBIS) with all the macroeconomic variables simultaneously. The equation of Toda-

Yamamoto multivariate model is: lnJII t

= 𝛽

0

+ ∑ 𝐾 𝑘=1 𝛽 k lnJII 𝑡−𝑘

+ ∑ 𝑑1max 𝑑1=1 𝛽

K+d1 lnJII 𝑡−𝐾−𝑑1

+ ∑ 𝑁 𝑛=0 𝛿 n rSBIS 𝑡−𝑛

+

∑ 𝑑2max 𝑑2=1 𝛿

𝑁+𝑑2 rSBIS 𝑡−𝑁−𝑑2

+ ∑

𝐼 𝑖=1 𝜏 i

X 𝑖𝑡

+ 𝜀 𝑡

.

11

rSBIS t

= 𝜃

0

+ ∑ 𝐾 𝑘=1 𝜃 k rSBIS 𝑡−𝑘

+ ∑ 𝑑1max 𝑑1=1 𝜃

K+d1 rSBIS 𝑡−𝐾−𝑑1

+ ∑ 𝑁 𝑛=0

π n lnJII 𝑡−𝑛

+

∑ 𝑑2max 𝑑2=1

π

𝑁+𝑑2 lnJII 𝑡−𝑁−𝑑2

+ ∑ 𝐼 𝑖=1 𝜑 i

X 𝑖𝑡

+ 𝜐 𝑡

.

where: k and n are the lagged period in VAR model; d1max and d2max are the integration’s order of time series data obtained using stationarity test procedures; X i

are the macroeconomic variable where i = lnM2, lnER, rSBI, IPI, INF, FFR and lnOP; β

0

and θ

0

are the constant; β k

, δ n

, τ

1

, θ k

, π n

and φ

1

are the coefficient of variables; ε t

and υ t

are the white noise disturbance term that assumed that E(ε t

) or E(υ t

) = 0, and E(ε t

υ t

) = 0.

5.4 Stationarity testing

Toda-Yamamoto (1995) causality test starts with testing the stationarity of data to determine the order of integration of time series data into stationary ones. Based on these test results, the value of d max

which is a vital component in determining time intervals on Toda-Yamamoto

(1995) methods is generated. In this study, the stationarity test was done by using two methods: the augmented Dickey-Fuller test (ADF test) and Phillips-Perron test (PP test).

5.5 The optimum lag (k) testing using the VAR model

There are several parameters to determine the optimum lag (k), namely the Akaike

Information Criterion (AIC), Schwarz Information Criterion (SIC), and Hannan Quinn

Criterion (HQC). In this study, the optimum lag test was conducted by SIC and HQC. SIC is more consistent in the lag selection compared to AIC. The greater the sample number in the model is, the more conical to the SIC probability of the selection of the appropriate lag.

Conversely, AIC is not consistent with the number of the samples used (Shittu and Asemota,

2009). Hurvich and Tsai (1989) stated that HQC equals to SIC, they are consistent in the selection of the lag in the estimation model. If the SIC and HQC show differences in the selection of lag, this study will refer to the SIC.

5.6 Establishment of optimum lag based-VAR system

Toda-Yamamoto causality test (1995) was preceded by the establishment of the VAR model based on the new optimum lag (p). The p-value is derived from the value of k plus d max

(p = k

+ d max

). If the stationary time series data in the first derivation (d max

= 1) and the optimum time interval of VAR model (k) equal to 1, the time interval for the Toda-Yamamoto equals to 2 (p = k + d max

= 1 + 1 = 2).

12

5.7 Estimation of VAR models with the methods of seemly unrelated regression (SUR)

VAR models (bivariate and multivariate) that have been formed, then are estimated using the

SUR method with an interval p = k + d max

. Rambaldi and Doran (1996) said that MWald test to test Granger causality can improve efficiency when the SUR method is used in the estimation (Akçay, 2011). Furthermore, Alaba, Olobusoye and Ojo (2010) stated that the use of SUR model is more efficient than ordinary least square (OLS) and two-stage least square

(2SLS). SUR method takes into account the correlation between errors in the equation measured at the same time, while the OLS assumes errors as something independent (Alaba and Olobusoye, 2010).

5.8 Restrictions on the parameters with the modified Wald (MWald) test

After estimating the VAR models (bivariate and multivariate) with SUR model, the next step is to make restrictions on the parameter by using the MWald test procedures. This MWald test becomes the differentiation between Toda-Yamamoto (1995) causality test and the

Granger causality test.

6. Analysis Results

6.1 Analysis of stationarity test results

The results of the stationarity test of each variable can be seen in Table 2.

Based on the ADF test it was found that all the variables are not stationary at level. Whereas in the PP test, there is only one variable that is stationary in nature at the level, which is LnER. Thus, differencing across all variables to obtain stationary data is necessary. At the first differencing, seven variables have been stationary, which is LnJII, rSBIS, LnER, rSBI, IPI, INF and LnOP, and the rest, which is LnM2 and FFR, have not been stationary. After conducting the second differencing, all variables have been stationary.

Table 2 Results of stationarity test

Research variable

ADF test PP test

Level 1 st

different 2 nd

different Level 1 st

different 2 nd

different

LnJII -1.22 -8.44*** -10.00*** rSBIS -1.18 -12.91*** -8.42***

-1.21

-2.48

-8.58***

-15.10***

-22.70***

-39.05***

LnM2 1.43 -2.46 -7.83*** 2.78 -11.47*** -47.43***

LnER -2.57 -9.08*** -11.01*** -2.93** -8.99*** -20.28*** rSBI -2.75* -4.90*** -13.12*** -2.49 -4.93*** -15.34***

13

Research variable

IPI

INF

FFR

ADF test PP test

Level 1 st

different 2 nd

different Level 1 st

different 2 nd

different

0.61 -4.62*** -8.74*** -2.64* -23.56*** -185.45***

-2.65* -8.92*** -10.38***

-2.79* -2.80* -14.41***

-2.47

-0.97

-8.95***

-14.49***

-27.81***

-68.60***

LnOP -2.03 -8.62*** -12.11*** -2.17 -8.60*** -36.50***

Note: *** indicate significant at 1%, ** significant at 5%, and * significant at 10%.

6.2 Analysis in determining optimum lag

In determining the optimum lag on the VAR system, we employ SIC and HQC criteria (see

Table 3 ). Using the lag optimum test results (k) on the bivariate and multivariate VAR and the maximum order of integration (d max

), Toda-Yamamoto lag is calculated by summing the two components (see Table 4).

Table 3 Summary of lag optimum VAR using SIC and HQC criteria

Bivariate: LnJII and other variables

LnJII and LnM2

LnJII and LnER

LnJII and rSBI

LnJII and IPI

LnJII and INF

LnJII and FFR

LnJII and LnOP

Bivariate: rSBIS and other variables rSBIS and LnM2 rSBIS and LnER rSBIS and rSBI rSBIS and IPI rSBIS and INF rSBIS and FFR rSBIS and LnOP

Multivariate

LnJII and all variables rSBIS and all variables

2

0

4

0

1

1

SIC

Optimum lag (k)

HQC

2

0

2

1

1

1

0

4

0

1

1

1

4

1

3

0

2

3

2

2

2

2

4

2

2

2

14

Table 4 Calculation of Toda-Yamamoto lag

Bivariate: LnJII and other variables

LnJII and LnM2

LnJII and LnER

LnJII and rSBI

LnJII and IPI

LnJII and INF

LnJII and FFR

LnJII and LnOP

Bivariate: rSBIS and other variables rSBIS and LnM2 rSBIS and LnER rSBIS and rSBI rSBIS and IPI rSBIS and INF rSBIS and FFR rSBIS and LnOP

Multivariate

LnJII and all variables rSBIS and all variables

Optimum lag (k)

2

0

1

1

0

4

0

3

0

2

2

0

4

0

1

1

Maximum order of integration (d max

)

2

1

1

1

1

2

1

2

1

1

1

1

2

1

2

2

Toda-Yamamoto lag

(p=k+d max

)

4

1

2

2

1

6

1

5

1

3

3

1

6

1

3

3

6.3 Content Analysis using bivariate VAR model: LnJII and rSBIS

After the degree of integration (d max)

and the optimum lag (k) of each relationship pattern between rSBIS and LnJII with macroeconomic variables are obtained, both in bivariate ways and in multivariate ways, then the next step is to develop a new VAR model based on the lag method of Toda-Yamamoto (p = d max

+ k

).

After the new VAR model is formed, estimation employing the method of seemingly-unrelated regression (SUR) to examine the causality relationship of each macroeconomic variable with LnJII and rSBIS. The null hypothesis is that either rSBIS or LnJII does not result in one-way Granger causality to any macroeconomic variables. The criteria to reject the null hypothesis employ the Wald statistic test. Rejection of the null hypothesis suggests that there is a causality relationship between

LnJII and rSBIS with the macroeconomic variables. The results of Toda-Yamamoto (1995)’s bivariate causality test with the interval (p) are shown in Table 5 .

15

Table 5 Result summary of Toda-Yamamoto’s bivariate causality test

LnJII rSBIS

Dependent variable

Wald test Probability Wald test Probability

LnM2 0.91 0.34 0.54 0.46

LnER 8.51 0.0035*** 0.21 0.65 rSBI 5.49 0.019** 0.07 0.79

IPI 0.13 0.71 1.05 0.30

INF 0.31 0.57 0.41 0.52

FFR 2.24 0.13 0.66 0.42

LnOP 2.47 0.12 1.22 0.27

Note: *** indicate significant at 1%, ** significant at 5%, and * significant at 10%.

Based on Table 5 it can be concluded that with the significance level of 5%, the sharia capital market returns incorporated in the JII have more information content related to macroeconomic variables than the returns of SBIS. Based on the results of Toda-Yamamoto’s bivariate causality test, LnJII leads to one-way Granger causality over two macroeconomic variables, namely changes in the exchange rate of Rupiah against the U.S. dollar (lnER) and

SBI interest rates (rSBI).

The test results in Table 5 can be explained using the mechanism of monetary policy through the exchange rates as shown in Figure 2 and 3.

Mundel (1962) described how monetary policy affects exchange rates and therefore affects output and inflation. Mundel

(1962) showed that perfect capital mobility will lead to the relationship between short-term interest rates and exchange rates. The differences in interest rates between two countries equal to the expected changes in the exchange rates between the two countries. Capital inflow in countries with high interest rates will continue to occur if the equilibrium has not been reached.

In other words, if Bank Indonesia carries out monetary operations by making changes in interest rates in domestic money markets, there will be differences in interest rates at home and abroad. It will have an impact on the magnitude of the flow of funds from and to abroad, one of which can be represented from the movement of stock markets (in this study, JII).

Such movement of capital flows is closely related to the supply and demand of money which in turn will influence exchange rates and inflation targets. Then, Bank Indonesia will respond to the rate of inflation through the monetary instrument namely SBI to obtain the level of inflation target targeted.

16

On the other hand, regarding the test of SBIS’ returns of the same significance level of

5%, as shown in Table 5, rSBIS does not causes one-way Granger causality toward the macroeconomic variables tested. From the results of Toda-Yamamoto’s bivariate causality test, it can be concluded that the JII contains more information related to macroeconomic variables than the SBIS. This suggests that the JII is more able to describe the movement of macroeconomic variables if compared to SBIS. Therefore, based on the test results of the bivariate model, the JII is worth considering as a policy indicator better than rSBIS.

6.4 Analysis of multivariate VAR models using the new time intervals (p)

The use of only two variables in the previous testing system of Toda-Yamamoto causality methods of bivariate models remains possible, allowing misspecification in the model. Thus, it is necessary to estimate the multivariate model (Kassim and Abdul-Manap, 2008). The multivariate model is a causality test of Toda-Yamamoto method conducted between LnJII and rSBIS with the overall macroeconomic variables. The causality test results of Toda-

Yamamoto method of multivariate models are presented in Table 6 below.

Table 6 Result summary of Toda-Yamamoto’s multivariate causality test between

LnJII/rSBIS toward the macroeconomic variables

Dependent variable

LnM2

LnER rSBI

IPI

INF

FFR

Wald test

LnJII

Probability

2.60

6.65

2.83

0.00

0.90

0.01

0.11

0.01***

0.09*

0.99

0.34

0.93

Wald test rSBIS

1.20

0.19

0.15

4.62

0.14

0.76

Probability

0.27

0.66

0.70

0.03**

0.71

0.38

LnOP 0.39 0.53 0.01 0.90

Note : *** indicate significant at 1%, ** significant at 5%, and * significant at 10%.

Based on Table 6 , from the results of Toda-Yamamoto’s multivariate causality test, it can be concluded that with the significance level of 5%, LnJII triggers one-way Granger causality over macroeconomic variables, namely changes in the exchange rates of Rupiah against the U.S. dollar (lnER). With the significance rate of 10%, LnJII results in one-way

Granger causality over the interest rates of the SBI (rSBI). This multivariate test result is consistent for the macroeconomic variables and supports the previous results of Toda-

Yamamoto (1995)’s bivariate causality test (Table 5).

In Toda-Yamamoto’s bivariate test,

17

LnJII leads Granger causality over LnER and rSBI at the same significance level of 5%.

Different from the results of Toda Yamamoto’ bivariate causality test on rSBIS over macroeconomic variables (Table 5), based on the the results of Toda-Yamamoto’s multivariate causality test in Table 6 it can be assumed that with the significance level of 5% rSBIS triggers one-way Granger causality over macroeconomic variable specifically the

Industrial Production Index (IPI). IPI is a proxy for economic growth reflecting the quantity of national industry products by assessing the physical quantity of the output. In other words,

IPI represents the changes in the economy of Indonesia and becomes one of the indicators for the economic growth of Indonesia. The presence of the relationship of one-way Granger causality between the rSBIS and the IPI indicates that Islamic finance, especially sharia money markets along with their systems and instruments, have something to do with the development of the real sector that has a real impact on the economy.

The rSBIS leads to Granger causality over only one macroeconomic variable, namely the Industrial Production Index (IPI). It can be explained that the transmission of sharia monetary policy through the financing way in Indonesia Islamic banking has the ultimate goal of economic growth and the stability of the money value (Ascarya, 2012)). Simply put, this can be written down as follows:

IPI = f (IFIN, IDEP, PUAS, SBIS)

Where: IPI is the industrial production index, IFIN is the sharia banking financing; IDEP is the DPK of Islamic banks; PUAS is the interest rate in a certain day in the Islamic interbank money market; SBIS is the returns of Bank Indonesia Sharia Certificate.

From the function of IPI, and Figure 2, it can be seen that when the monetary authority, in this case BI, establishes policies concerning the interest rates of SBI, it will affect the returns of SBIS and further affect the returns of PUAS. This PUAS will affect the level of the sharing of savings, deposits and financing (PLS). When the sharing of savings/deposits set by the bank increases, then by assuming the ceteris paribus of the number of the DPK of Islamic banking (IDEP) owned by the bank will also increase.

Furthermore, the bank will use this excess of liquidity by distributing it in the form of financing or credit (IFIN) to move the real sector of Indonesia (IPI).

From the results of Toda Yamamoto’s multivariate causality test, it can be concluded that if LnJII and rSBIS are tested simultaneously against macroeconomic variables, with the significance level of 5%, LnJII has more influences on LnER while rSBIS has more influences on IPI.

18

6.5 Analysis of VAR model formation between macroeconomic variables and LnJII/rSBIS

To see whether the causality relationship that occurs between LnJII/rSBIS and macroeconomic variables is one-way or two-way, we conducted the Toda-Yamamoto (1995) causality test with the null hypothesis that macroeconomic variables do not lead to one-way

Granger causality over LnJII or rSBIS. Results summary of Toda-Yamamoto (1995)’s bivariate causality test between macroeconomic variables with LnJII and rSBIS at the intervals (p) that have been obtained from Table 3 and 4, are shown in Table 7 .

Table 7 Results summary of Toda-Yamamoto’s bivariate causality test between macroeconomic variables and LnJII/rSBIS

Independent variable

LnM2

LnER rSBI

IPI

Wald test

0.70

LnJII

Probability

0.40

2.83

2.06

0.03

0.09*

0.15

0.87

Wald test

0.06 rSBIS

0.58

0.12

0.00

Probability

0.81

0.45

0.73

0.96

INF

FFR

2.13

0.07

0.14

0.80

0.80

0.00

0.37

0.96

LnOP 1.15 0.28 0.40 0.53

Note : *** indicate significant at 1%, ** significant at 5%, and * significant at 10%.

From Table 7 , it can be seen that none of the macroeconomic variables that causes the one-way Granger causality over both LnJII and rSBIS with the significance level of 5%.

However, if the significance level increases to 10%, based on the result of Toda-Yamamoto

(1995)’s bivariate causality test, it can be seen that LnER causes one-way Granger causality over LnJII. This result supports the research conducted by Abdul Majid and Yusof (2009) that one of the variables significantly affecting the stock movement of Kuala Lumpur Syariah

Index (KLSI) is the exchange rate (REER), in addition to Board Money Supply (M3),

Treasury Bill Rates (TBR), and Federal Fund Rate (FFR).

Table 8 Results summary of Toda-Yamamoto’s multivariate causality test between macroeconomic variables and LnJII/rSBIS

Independent variable

LnM2

LnER rSBI

IPI

Wald test

2.07

LnJII

Probability

0.15

0.88

3.10

0.29

0.35

0.08*

0.59

Wald test

0.44 rSBIS

Probability

0.51

0.71

5.33

0.05

0.40

0.02**

0.82

19

Independent variable

INF

FFR

Wald test

LnJII

Probability

3.25

1.61

0.07*

0.20

Wald test

4.09

0.19 rSBIS

Probability

0.04**

0.66

LnOP 5.60 0.02 0.00 0.97

Note : *** indicate significant at 1%, ** significant at 5%, and * significant at 10%.

Table 8 shows the results of Toda-Yamamoto (1995)’s multivariate causality test, with the significance level of 5%, indicate that rSBI and INF cause one-way Granger causality over rSBIS. On the contrary to findings in table 7, none of the macroeconomic variables that leads to one-way Granger causality relationship over LnJII. However, if the significance level is increased to 10% and the variables of INF and rSBI simultaneously cause one-way Granger causality over LnJII and rSBIS. Table 9 presents the summary of the method of Toda-Yamamoto (1995) causality test between LnJII and rSBIS with macroeconomic variables at the significance level of 5%.

Table 9 Results summary of two-way causality test of Toda-Yamamoto’s bivariate

Macroeconomic variable

LnM2

LnER rSBI

IPI

INF

FFR

LnOP

LnJII

>--<

>--<

>--<

>--<

>--< rSBIS

>--<

>--<

>--<

>--<

>--<

>--<

>--<

Table 9 summarizes the results of two-way causality test of Toda-Yamamoto

(1995)’s bivariate methods and shows that there is no macroeconomic variable having a causality relationship with rSBIS while LnJII has a one-way relationship with LnER and rSBI.

Table 10 Results summary of two-way causality test of Toda-Yamamoto’s multivariate

LnJII

>--<

>--<

>--<

>--<

>--<

>--< rSBIS

>--<

>--<

>--<

>--<

Macroeconomic variable

LnM2

LnER rSBI

IPI

INF

FFR

LnOP

20

Table 10 summarizes the results of two-way causality test of Toda-Yamamoto (1995)’s multivariate methods and shows that LnM2 has no causality relationship with LnJII and rSBIS; LnER has a one-way relationship with LnJII and no causality relationship with rSBIS; rSBI has no causality relationship with LnJII but it has a one-way relationship with rSBIS;

IPI has no causality relationship with LnJII but it has a one-way relationship with rSBIS; INF has no causality relationship with LnJII but it has a one-way relationship with rSBIS, and both FFR and LnOP have no causality relationship both with LnJII and rSBIS.

7. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Through the examination of the Toda-Yamamoto (1995)’s VAR causality relationship between macroeconomic variables and Islamic financial markets, this study is aimed to examine and compare the information content related to the macroeconomic variables contained in the sharia capital market (JII) and sharia money market (SBIS). Between the two

Islamic financial variables, one that contains more information is the better candidate for policy indicators.

Several conclusions can be drawn from these research findings. First, that the twoway bivariate test results between the returns of JII and the ones of SBIS with one of macroeconomic variables in turn indicate that the JII has two types of information content related to macroeconomic variables, namely changes in the exchange rate of Rupiah against dollar (LnER) and changes in interest rates of SBI (rSBI). In the other hand, the test results of the SBIS variable show that SBIS does not have any information content related to macroeconomic variables. Second, that the two-way multivariate test results between JII and

SBIS with the whole macroeconomic variables simultaneously indicate that the JII only has one type of information content related to macroeconomic variables, namely changes in the exchange rate of Rupiah against dollar (LnER). While SBIS has three types of information content related to macroeconomic variables, namely changes in the interest rates of SBI

(rSBI), the Industrial Production Index (IPI), and inflation (INF). Third, through the two-way bivariate test, JII is able to describe the movement of macroeconomic variables better as it has two types of information content related to macroeconomic variables, namely LnER and rSBI, while SBIS fails to describe the movement of macroeconomic variables at all. Fourth, through the two-way multivariate test, SBIS has more information content than JII does. In other words, Sharia Money Market can describe the movement of the macroeconomics more.

21

From the perspectives of policy makers, these different findings provide some insights and a variety of policy implications. For example, it was found that LnJII led to one-way

Granger causality over two macroeconomic variables, namely changes in the exchange rate of Rupiah against the U.S. dollar and the interest rates of SBI. Mundel (1962) shows that perfect capital mobility will lead to the relationship between short-term interest rates and the exchange rates. Differences in interest rates between two countries equal to the expected changes in the exchange rates of the two countries. Capital inflow in countries with high interest rates will continue to occur if the equilibrium has not been reached. In other words, if

Bank Indonesia carries out monetary operations by making changes in interest rates in domestic money markets, there will be differences in interest rates at home and abroad. This will have an impact on the magnitude of the flow of funds from and to abroad, one of which can be represented from the movement of stock markets (in this study, JII). Such movement of capital flows is closely related to the supply and demand of money which in turn will influence exchange rates and inflation targets. Then, Bank Indonesia will respond to the rate of inflation through the monetary instrument namely SBI to obtain the level of inflation target targeted.

The second implication is that a relationship of one-way Granger causality between the returns of SBIS and the ones of IPI was found. IPI is a proxy for the economic growth reflecting the quantity number of national industrial products by assessing the physical quantity of the output. In other words, IPI represents the changes in the economy of Indonesia and becomes one of the indicators for the economic growth of Indonesia. This indicates that

Islamic finance, along with their systems and instruments, has something to do with the development of the real sector that has a real impact on the economy. That when the monetary authority, in this case Bank Indonesia, establishes policies concerning the interest rates of SBI, it will affect the returns of SBIS and further affect the returns of PUAS. This

PUAS will affect the level of the sharing of savings, deposits and financing. When the sharing of savings/deposits set by the bank increases, then by assuming the ceteris paribus of the number of the DPK of Islamic banking (IDEP) owned by the bank will also increase.

Furthermore, the bank will use this excess of liquidity by distributing it in the form of financing or credit to move the real sector of Indonesia.

The third implication is that the contradiction in these findings indicates the presence of (i) interaction between the macroeconomic variables, (ii) interaction between the financial market and the macroeconomic variables, and (iii) interaction between the Islamic capital market and money market. Further, by considering these interactions, SBIS tends to have

22

more information contents than JII and more suitable for use as a barometer of monetary policies in Indonesia.

8. Suggestions for Further Research

This study has several limitations. For further research, we provide some input as suggestions that can be adapted. First, about the methodology, which is the Augmented VAR model developed by Toda and Yamamoto (1995). Although it can project the causality relationship among the research variables, it is unable to identify the lagging or how long it takes for a variable in influencing the other variables. Thus, the other types of VAR models can be used to examine the lagging of each research variable in influencing the other variables. Second, in relevance to macroeconomic variables, this study uses the variable M2 indicating the number of broad money supply, the Industrial Production Index (IPI) as a proxy for economic growth, and OP as the representation of the world oil price in the WTI market (the U.S.). For further research, similar and identical variables may be selected such as Brent market (UK) for world oil prices, M1 for narrow money supply, and other variables that can reflect economic growth considering that the variable IPI does not accommodate the output value of UKM.

References

Abdul Majid, M. S., and R. M. Yusof (2009). Long-run relationship between Islamic stock returns and macroeconomic variables: An application of the autoregressive distributed lag model . Humanomics , Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 127-141.

Abdul Rahman, A., N. Z. M. Sidek and F. H. Tafri (2009).

Macroeconomic determinants Of

Malaysian stock market. African Journal of Business Management , Vol.3, No. 3, pp. 95-

106.

Akçay, S. (2011). Causality relationship between total R&D investment and economic growth: Evidence from United States .

The Journal of Faculty of Economics and

Administrative Sciences , Vol. 16, No.1, pp. 79-92.

Alaba, O. O., E. O. Olubusoye, and S. O. Ojo (2010). Efficiency of seemingly unrelated regression estimator over the ordinary least square. European Journal of Scientific

Research , Vol. 39, No. 1, pp.153-160.

Ali, S. S. (2005). Islamic capital market products: Developments and challenges. Occasional

Paper No. 9 (IRTI), pp. 1-92.

23

Ando, A., and F. Modigliani (1963). The “life-cycle hypothesis of saving: Aggregate implications and tests. American Economic Review , Vol. 53, No. 1, pp. 55-84.

Armanious, A. N. R. (2007). Globalization effect on stock exchange integration . SSRN

Working Paper (http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1929045).

Ascarya (2012). The transmission channel and the effectivity of the dual monetary policies in

Indonesia .

Monetary Economic and Banking Bulletin , Vol. 14, No. 3, pp. 283-315.

Beckers, S., G. Connor, and R. Curds (1996). National versus global influences on equity returns. Financial Analysts Journal , Vol. 52, No. 2, pp. 31-39.

Büyükşalvarci, A., and H. Abdioğlu (2010).

The causal relationship between stock prices and macroeconomic variables: A case study for Turkey. International Journal of Economic

Perspectives , Vol. 4, No. 4, pp. 601-610.

Castanias, R. P. (1979). Macro Information and the variability of stock market prices. Journal of Finance , Vol. 34, No. 2, pp. 439–450.

Chiarella, C., and S. Gao (2004). The value of the S&P 500 — a macro view of the of the stock market adjustment process. Global Finance Journal , Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 171–196.

Choi, J. J., and M. Rajan (1997). A joint test of market segmentation and exchange risk factor in international capital market. Journal of International Business Studies , Vol. 28, No. 1, pp. 29-49.

DeFina, R. H. (1991). Does inflation depress the stock market? Business Review , Issue

November 1991, pp. 3-12.

Degiannakis, S., G. Filis and C. Floros (2013). Oil and stock returns: Evidence from

European industrial sector indices in a time-varying environment. Journal of

International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money (in press, accepted manuscript).

Dorodnykh, E. (2012). What is the degree of convergence among developed equity markets?

International Journal of Financial Research , Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 1-16.

Engle, R. F., and C. W. J. Granger (1987). Co-integration and error correction:

Representation, estimation, and testing. Econometrica , Vol. 55, No. 2, pp. 251-276.

Filis, G. (2010). Macro economy, stock market and oil prices: Do meaningful relationships exist among their cyclical fluctuations? Energy Economics , Vol. 32, No. 4, pp. 877-886.

Friedman, M. (1988). Money and the stock market. Journal of Political Economy , Vol. 96,

No. 2, pp. 221-245.

Hardouvelis, A.G. (1988). Stock prices: nominal vs. real shocks. Financial Markets and

Portfolio Management , Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 10–18.

24

Hidayat, T. (2007). The effect of inflation on the performance of Islamic banking’s financing, the transaction volume of interbank Islamic money market (PUAS) and the position of outstanding Bank Indonesia wadiah sertificate (SWBI) . University of Indonesia: undergraduate thesis.

Hooker, M. A. (2004). Macroeconomic factors and emerging market equity returns: a

Bayesian model selection approach. Emerging Markets Review , Vol. 5, No. 4, pp. 379–

387.

Heaney, R., V. Hooper, and M. Jaugietis (2002). Regional integration of stock markets in

Latin America. Journal of Economic Integration , Vol. 17, No. 4, pp. 745 – 760.

Hurvich, C. M., and C. L. Tsai (1989). Regression and time series model selection in small samples. Biometrika , Vol. 76, No. 2, pp. 297-307.

Husnan, S., and E. Pudjiastuti (1994). International diversification: Observation on Asia-

Pacific markets. Kelola , Vol. 3, No. 5, pp. 107-118.

Hussin, M. Y. M., F. Muhammad, M. F. Abu Hussin, and A. Abdul Razak (2012). The

Relationship between oil price, exchange rate and Islamic stock market in Malaysia.

Research Journal of Finance and Accounting , Vol. 3. No. 5, pp 2222-2847.

Iqbal, Z., and H. Tsubota (2006). Emerging Islamic capital markets: a quickening pace and new potential. In The Euromoney Yearbooks (2006): International debt capital markets handbook . Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Johansen, S. (1991). Estimation and hypothesis testing of cointegration vectors in Gaussian vector. Econometrica , Vol. 59, No. 6, pp. 1551-1580.

Johansen, A., and K. Juselius (1990). Maximum likelihood estimation and inference on cointegration — with applications to the demand for money. Oxford Bulletin of

Economics and Statistics, Vol. 52, No. 2, pp. 169–210.

Kassim, S. H., and T. A. Abdul Manap (2008). The information content of the Islamic interbank money market rate in Malaysia. International Journal of Islamic and Middle

Eastern Finance and Management , Vol. 1, No. 4, pp. 304-312.

Levine, R., and Zervos, S. (1996). Stock Market Development and Long-Run Growth. The

World Bank Economic Review , Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 323–339.

Maysami, R. C., and T. S. Koh (2000). A vector error correction model of the Singpore stock market. International Review of Economics and Finance , Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 79-96.

Mishkin, F. S. (2004). The economics of money, banking, and financial markets , the 9 th edition. USA: Prentice Hall.

25

Moschitz, J. (2004). The determinant of the overnight interest rate in the Euro area. European

Central Bank Working Paper Series No. 393/September 2004 .

Mundell, R. A. (1962). The Appropriate use of monetary and fiscal policy for internal and external stability. Staff Papers - International Monetary Fund , Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 70-79.

Ningsih, S. (2011). Information contents regarding macroeconomic variables of conventional money market rate and Islamic money market rate with Toda-Yamamoto causality test method for the periode January 2003- December 2010.

University of Indonesia: undergraduate thesis.

Park, J. W., and R. A. Ratti (2008). Oil price shocks and stock market in the U.S. and 13

European countries. Energy Economics, Vol. 30, No. 5, pp. 2587-2608.

Rambaldi, A., and H. Doran (1996). Testing for Granger non-causality in cointegrated systems made easy . University of New England: Working Papers in Econometrics and

Applied Statistics.

Sadorsky, P. (1999). Oil price shocks and stock market activity. Energy Economics , Vol. 21,

No. 5, pp. 449–469.

Shirazi, N. S., and T. A. A. Manap (2005). Export ‐ led growth hypothesis: Further econometric evidence from South Asia. The Developing Economies , Vol. 43, No. 472-

488.

Shittu, O. I., and M. J. Asemota. (2009). Comparison of criteria for estimating the order of autoregressive process: A monte carlo approach. European Journal of Scientific

Research , Vol. 30, No. 3, pp. 409-416.

Toda, H. Y., and T. Yamamoto (1995). Statistical inference in vector autoregressions with possibly integrated processes. Journal of Econometrics , Vol. 66, No. 1–2, pp. 225–250.

Wahyudi, I., and F. Rosmanita. Islamic money market: formal instrument that not optimal . In

Yusuf, W. (2011), Indonesian Islamic Economic Outlook (ISEO) 2011 . Jakarta: Lembaga

Penerbit FEUI.

Yusof, M. R., and M. S. Abdul Majid (2007). Stock market volatility in Malaysia: Islamic versus conventional stock market. Journal of KAU: Islamic Economics , Vol. 20, No. 2, pp. 17-35.

Zapata, H. O., and A. N. Rambaldi (1997). Monte carlo evidence on cointegration and causation. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics , Vol. 59, No. 2, pp. 285–298.

26