Introduction on Energy Policy

advertisement

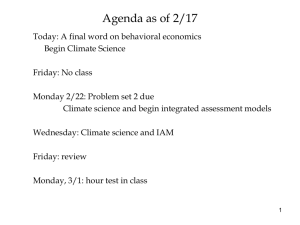

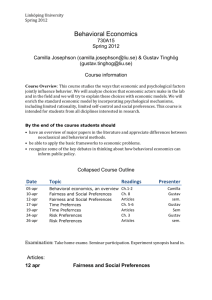

Economics after behavioral attack 1 Behavioral issues in energy and the environment Economics 331b Spring 2011 2 Agenda as of 2/16 Today: Behavioral economics Friday: Lint will lead review session Monday: Climate science Wednesday: Climate science and IAM Thursday: review material in sections Friday: midterm in class 3 Background Major grounds for government intervention in energy and environmental markets: 1. Market failures (uninternalized externalities such as CO2 emissions, oil premium, …) 2. Behavioral failures (informational, decisional, etc.) 4 A central behavioral puzzle: First-cost v. deferred cost The energy efficiency puzzle: Consider the life-cycle cost (LCC) of an automobile: LCC = Purchase price + ∑(1+r)-t FutureCostt = First cost + Deferred cost Finding: Deferred cost is generally discounted by 50% or more. What is going on here? 5 The challenge to mainstream economics Here are some issues of decision theory from standard economics that are challenged (from least to most damaging): 1. 2. 3. 4. People have good information and/or process information efficiently (data competence) People act to optimize their preferences relative to information and resources (decision competence) Institutions are appropriately designed so that people acting rationally will make good decisions (good institutions). People have self-interested and stable preferences over consumption of goods, services, and capital (non-weird preferences) Behavioral economics challenges all of these. 6 1. Informational incompetence Classical view: People have good information and/or process information efficiently Behavioral view: People have all kinds of biases in structuring information (law of small numbers, overconfidence, anchoring, hindness bias) Examples of overconfidence effect: • Second-year MBA students overestimated the number of job offers they would receive and their starting salary. • Students overestimated the scores they would achieve on exams. • Almost all newlyweds in a US study expected their marriage to last a lifetime, even while aware of the divorce statistics. • Most smokers believe they are less at risk of developing smokingrelated diseases than others who smoke. 7 What did people do in buying a car relative to a survey? 8 2. Decision incompetence Classical view: People act to optimize their preferences relative to information and resources Behavioral view: People make all kinds of trivial and tragic mistakes in daily life Examples: • Bet on red because red “is due to come up soon.” • 4 million unwanted pregnancies a year • 37,000 traffic fatalities in 2008 • Addictions (smoking, alcohol, …) • Default option matters in pension decisions, organ transplants • Refusal to lower the asking price on house because it is below the price you paid for your house? • MPG illusion 9 Defaults matter for organ transplants Eric J. Johnson and Daniel Goldstein, “Do Defaults Save Lives?” Science, Nov 2003. 10 3. Bad incentives and institutions Classical: Institutions are structured so that rational actors will produce efficient decisions Behavioral: All kinds of principal-agent problems get in the way Examples: – Energy pricing: Yale pays the electricity bill, so the price of higher energy use to students and faculty is…. ZERO. – Tax distortions – Political: what are the incentives for political leaders to set MSB=MSC? 11 Zero marginal cost energy 12 Effect of energy incentives on energy in rent v. own 13 International Energy Agency, Ming the Gap, 2007 4. Weird* preferences Classical: People have self-interested preferences over consumption of goods, services, and capital (standard preferences) Behavioral: People are altruistic, care about fairness, will contribute to the public good, have spite. Examples: • Prisoners’ dilemma: In fact, people are much more likely to cooperate than the PD game would predict. (Good news for public goods) • Spite: But some people will fight to the death and bring everyone else down with them (Hitler) In sense of not conforming to classical economics. Not purely concerned with optimizing a stable, time-consistent, purely self-interested, complete set of preferences over all market and non-market goods and services for all periods in the future. Also, altruistic, kinky, funky, wild, erratic, spaced-out, random, slapdash. 14 Weird preferences (cont.) Classical: People have well-defined and stable preferences over goods and time (stable preferences) Behavioral: People have status-quo bias, reference levels, adaption, loss aversion, hyperbolic discounting, uncontrollable passion or rage Examples: – Hyperbolic preferences: overdiscount future pains and benefits – Difference between willingness to pay and willingness to accept in contingent valuation studies (for say species extinction) – More important is adaptation to current situation: happiness paradox, lottery winners, quadriplegics, “rat race” or “treadmill” syndrome 15 What are policy responses For first three, not deep philosophical issues and requires education, better information, nudges: • Data incompetence: provide better data or simplify calculations (labeling, $ labeling on energy using appliances) • Decision incompetence: “Nudge” to more sensible decisions with different default options (“soft parentalism”). • Bad institutions need fixing (meter Yale rooms?) For last one, deep philosophical and political issue about whether should respect individual preferences: • Preferences: – “Weird” preferences: Shouldn’t we respect them? – Incoherent preferences: Should governments override them? Treat people like children? 16 What should we think about? • The gasoline paradox: People pay $0.37 for $1 of PV of gasoline savings? • The organ transplant opt-in/opt-out paradox. 17 First-cost v. future cost The energy efficiency puzzle: Consider the life-cycle cost (LCC) of an automobile: LCC = purchase price + present value running costs = purchase price + ∑(1+r)-t FutureCostt Basic result is that the breakeven discount rate is 20+% p.y [E.g., Allcott and Wozny ≈ 60 % per year] What is going on here? • • • • • • Incomplete information about MPG or fuel prices? Risk or loss aversion? High discount rates and hyperbolic discounting? Principal-agent conflicts? Computational incompetence (bounded rationality)? Limited managerial time? 18 Defaults matter for organ transplants Eric J. Johnson and Daniel Goldstein, “Do Defaults Save Lives?” Science, Nov 2003. 19 The Zillion Dollar Question Are all these minor “anomalies” … or are they central to economic behavior? 20