Alexander Hamilton: an economic and military power modeled on

advertisement

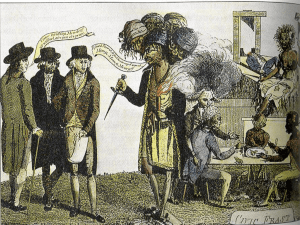

The New Nation In the 1790s, the US: 1. Implemented the US Constitution 2. Ratified a Bill of Rights 3. Built the capitol city in Washington, DC 4. Created the first political parties. There were two views of what the American nation should become: Alexander Hamilton: an economic and military power modeled on Britain, with a strong central government, a national bank, a standing army, and flourishing industry Thomas Jefferson: an agrarian society, no central bank, small army, very small central government In 1790, the first Census was held. Four million; most lived on the Atlantic coast One fifth of the population was black; of whites, three-fifths were English and onefifth was Scottish or Irish; rest was German, Dutch, French, Swedish; half of Americans in 1790 were under sixteen In 1790, the US faced many problems: 1. the challenge of building a sound economy 2. preserving national independence 3. creating a stable political system which provided a legitimate place for opposition 4. A huge debt remained from the Revolutionary War and paper money issued during the conflict was virtually worthless. 5. In violation of the peace treaty of 1783 ending the Revolutionary War, Britain continued to occupy forts in the Old Northwest. 6. Spain refused to recognize the new nation's southern and western boundaries. To secure the nation's credit, the first Treasury Secretary, Alexander Hamilton, had the federal government assume the entire indebtedness of the federal government and the states (assumption). To issue currency, collect taxes, hold government funds, regulate private banks, and make loans, he recommended that the federal government establish a Bank of the United States. The House: 1.passed a tariff on imports and a tax on liquor. 2. imposed duties on foreign vessels to encourage American shipping The House and the Senate: 1. created departments of State, Treasury, and War to provide a structure for the executive branch of the government, 2. passed the Judiciary Act of 1789 organized a federal court system, which consisted of a Supreme Court with six justices, a district court in each state, and three appeals courts. The Whiskey Rebellion, occurred in 1794, when over 7,000 frontiersmen marched on Pittsburgh to stop collection of the whiskey excise tax. Determined to set a precedent for the federal government's authority, Washington gathered an army of 15,000 soldiers to disperse the rebels, which he led to Pennsylvania. In the face of this overwhelming force, the uprising collapsed. The new government had proved that it would enforce laws enacted by Congress. In 1789, the French Revolution sent shock waves across the Atlantic. Many Americans, mindful of French aid during their own struggle for independence, supported the Revolution. At the same time, the British were once again inciting Native Americans to attack settlers in the West, hoping to destabilize the fledgling Republic. In 1793, Washington issued the Neutrality Proclamation, which said that America was neutral in the conflict between Great Brittan and France. In 1793, within days of Washington's second inauguration, France declared war on several European nations, including England. The Jefferson and Hamilton factions fought endlessly over the European conflicts. The French ambassador to the U.S. -- the charismatic, audacious "Citizen" Edmond Genet -- had meanwhile been appearing nationwide, drumming up considerable support for the French cause. Washington was deeply irritated by this subversive meddling, and when Genet allowed a French-sponsored warship to sail out of Philadelphia against direct presidential orders, Washington demanded that France recall Genet. In mid-1793, Britain announced that it would seize any ships trading with the French, including American vessels. In protest, riots erupted in several American cities. In 1794, Six large warships were commissioned; among them was the USS Constitution, the legendary "Old Ironsides." An envoy was sent to England to attempt reconciliation, but the British were now building a fortress in Ohio while increasing insurgent activities elsewhere in America. President Washington wanted a diplomatic solution. The envoy to England, John Jay, negotiated a treaty that eliminated British control of western posts within two years, established America's claim for damages from British ship seizures, and provided America a limited right to trade in the West Indies. However, the treaty failed to compensate Americans for slaves taken by the British during the Revolution. Worst of all, the treaty did not address the practice of impressment. Congress approved the treaty, with much criticism, and Washington signed it in 1795. In the Pinckney Treaty of 1795, Spain recognized U.S. borders at the Mississippi and the 31st parallel (the northern border of Florida, a Spanish possession.) Spain also granted Americans the right to use the Mississippi River to New Orleans, and this also opened much of the Ohio River Valley for settlement and trade. Jay's treaty with the British continued to have negative ramifications for the remainder of Washington's administration. France declared it in violation of agreements signed with America during the Revolution and claimed that it comprised an alliance with their enemy, Britain. By 1796, the French were harassing American ships and threatening the U.S. with punitive sanctions. Diplomacy did little to solve the problem, and in later years, American and French warships exchanged gunfire on several occasions. Adams's presidency, like that of Washington, was consumed with problems that arose from the French Revolution, The King and Queen (Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette) were executed, attempts at de-Christianization occurred, numerous foes of the Revolution -- especially aristocrats and monarchists -- were executed in the September Massacre (1792) and the Reign of Terror (1793-1794). The Jay Treaty plunged Adams into a foreign crisis that lasted for the duration of his administration. At first, Adams tried diplomacy by sending three commissioners to Paris to negotiate a settlement. However, Prime Minister Charles Maurice de Talleyrand of France insulted the American diplomats by first refusing to officially receive them. He then demanded a $250,000 personal bribe and a $10 million loan. This episode, known as the XYZ affair, sparked a white-hot reaction within the United States. Adams responded by asking Congress to appropriate funds for defensive measures. These included the augmentation of the Navy, improvement of coastal defensives, the creation of a provisional army, and authority for the President to summon up to 80,000 militiamen to active duty. Congress passed the Alien and Sedition Acts to curb dissent, created the Navy Department, organized the Marine Corps, and cancelled the treaties of alliance and commerce with France that had been negotiated during the War of Independence. Adams’ goal was to demonstrate American resolve and, he hoped, bring France to the bargaining table. During the fall of 1798 and the winter of 1799, he received intelligence indicating a French willingness to talk. When Talleyrand sent unofficial word that American diplomats would be received by the French government, Adams announced his intention to send another diplomatic commission to France. By the time the commissioners reached Paris late in 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte had become the head of the French government. After several weeks of negotiation, the American envoys and Napoleon signed the Treaty of Mortefontaine (The Convention of 1800) which released the United States from its Revolutionary War alliance with France and brought an end to the “Quasi-War” with France Adams subsequently said that the honorable peace he had arranged was the great jewel in his crown after nearly twenty-five years of public service.