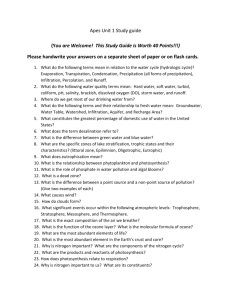

Presentation2

advertisement

1.22 Ozone layer is a concentration of ozone molecules in the stratosphere (10-50km above earth’s surface) Stratospheric ozone shields earth from sun’s ultraviolet (UV) rays, reducing radiation Increased UV radiation causes skin cancer, cataracts, weakened immune systems, reduce crop yield and impacts on marine systems Ozone molecules are attacked by ozone-depleting substances, such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) In the stratosphere, chlorine or bromine atoms split apart from ozone-depleting substances and destroy ozone molecules. One chlorine atom can break apart more than 100,000 ozone molecules (continued) 1.23 In the 1980s, an ‘ozone hole’ was identified above the Antarctic and concluded to be more than natural variations in concentrations International agreement such as Montreal Protocol have committed nations to phase-out or reduce ozone-depleting substances CFC production banned in developed countries since 1995 and alternatives have been developed 1.24 Biodiversity is defined as the variety of life on earth, including plants, animals and micro-organisms, along with the genetic material they contain and the ecological systems in which they occur Biodiversity is being eroded globally through native vegetation clearance, pollution of air, land and water, inappropriate land use, disruption of natural ecological cycles, invasion of exotic weeds and pests and depletion of forests, fisheries and other natural resources (continued) Australia is among the most biologically diverse nations in the world - 290,000 species of Australian flora and 200,000 species of Australian fauna. Currently 1,478 species and 27 ecological communities currently listed at the national level as either endangered or vulnerable We do not even know all species we are endangering or their potential for humans We do not know what overall impact steady degradation of ecosystems will have - the thin end of the wedge? 1.25 1.26 Threatens global ability to continue to produce food. By 1990, poor agricultural practices had contributed to degradation of 562 million hectares, (38% of the roughly 1.5 billion hectares in cropland worldwide. Each year, an additional 5 – 6 million hectares of land estimated to be lost to soil degradation Soil degradation includes: soil erosion by water and wind - depleting topsoil and causing water and wind pollution physical degradation through mechanical tilling desertification - the degradation of land in arid, semi-arid, and dry sub-humid areas, caused primarily by inappropriate land use and climatic variations. salinisation and waterlogging of soil depletion of soil nutrients through application of fertilisers loss of beneficial soil organisms through over-application of agricultural chemicals (continued) 1.27 Major causes of soil degradation include overworking soil mechanically, land clearing and deforestation, overgrazing, irrigation, and over-application of agricultural chemicals Soil erosion is expected to severely reduce agricultural production in regions including southeast Nigeria, Haiti and the Himalayan foothills, and part of southern China, Southeast Asia and Central America Over 250 million people are directly affected by desertification, with one billion people in over one hundred countries at risk Salinity affecting enormous areas of land and water quality in rivers. Saline areas can result from natural processes, however, most newly salinised areas are the result of changes in land use and hydrological cycles. Most salinity results from rising groundwater. Types of salinity include dryland, irrigation, urban, river and industrial 1.28 Source: former NSW Department of Land and Water Conservation We are steadily using up available non-renewable resources. Non-renewable resources = resources that are not replenished, or at least not replenished within hundreds of thousands of years, e.g. metals and fossil fuels We are harvesting many renewable resources at rates greater than their rate of replenishment (e.g. many forests) Use of energy from fossil fuels, which are effectively nonrenewable, is of huge concern. Fossil fuels include petrol, diesel, natural gas, LPG, black and brown coal, oil, kerosene and aviation gasoline 1.29 Energy use and environmental impacts are closely linked, as the extraction, transport and use of fuels and the production of electricity impact the environment on local, regional and global levels, particularly the enhanced greenhouse effect and global warming Global use of fossil fuel increased by over three and a half times between 1950 and 2000 (continued) 1.30 World fossil fuel consumption, 1950-2000 Source: Worldwatch Institute (2001) (continued) 1.31 Australia, which compared to many countries has large reserves in comparison to annual use, is nonetheless facing a decline in crude oil production over the next decade, with estimates that selfsufficiency for this product will decline from 85 percent in 2001 to less than 40 percent in 2010 In Australia, the ultimate constraint to use of non-renewable energy resources may well be the environmental impacts of extraction and consumption, rather than availability Potable water another critical resource being depleted, particularly in Australia. Australia is the world’s driest inhabited continent, yet in 1996/97 used 24,058 gigalitres (approx. 24 billion cubic metres) annually – an increase of 65 percent since 1985. There was a 75 percent increase in the annual volume of water used for irrigation between 1985 and 1996/97 (continued) 1.32 About one-third of the world’s population lives in regions with moderate to high water stress. If present consumption trends continue, two thirds of people in the world will live in water-stressed conditions by the year 2025 Extraction of non-renewable resources has many environmental impacts, but is also a social issue - current wasteful practices reduce the opportunities for future generations to access these resources to satisfy their own needs. Within current generations, there is enormous inequity in how resources are distributed, leading to increasing global tensions 1.33 Each year, every Australian contributes about one tonne of waste to landfill Of the 21.2 million tonnes of waste disposed of at landfills in 1996/97, approx. 40% domestic waste, 23% commercial and industrial waste, and 37% construction and demolition waste Waste is a problem not only because raw materials are not used to their full potential, but also because of disposal challenges (continued) Traditional approaches to waste management rely on the natural environment to absorb and assimilate unwanted byproducts. Environmental impacts associated with waste disposal include land contamination, methane emissions, leachate discharges, odour, flammability, toxicity, and consumption of land resources Landfill has been the most common method of dealing with solid waste in Australia. In large cities, and increasingly in towns, existing landfills are filling up and it is difficult to find new sites. Waste disposal costs have also risen substantially in recent decades Hazardous waste creates additional problems, as it is difficult and costly to safely treat, or store, such materials 1.34 1.35 Impacts of pollution to air, land and water include harm to human health, degradation of natural ecosystems, and loss of productive land resources In developed countries, pollution is now relatively well-regulated with significant penalties and industry has significantly improved its practices. However, we still have the burden of cleaning up many of the problems that have been caused from the polluting practices of many past industrial processes (continued) Some pollutants are extremely persistent, and do not readily break down in the environment. As a consequence, they can ‘bioaccumulate’ Minamata in Japan suffered one of the worst cases of industrial pollution in history Non-point source pollution, such as oil and litter in stormwater, still an environmental problem in Australia In many developing countries, where env. legislation nonexistent or not enforced, industrial pollution remains a serious problem 1.36