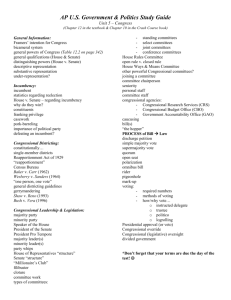

The Congress and Its Work

copyright 2004

Chapter Pearson-Longman

12

Congress: The First Branch

• Called this

because the

Constitution

lays out the

powers and

structure of

Congress in

Article I.

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004

Congress: The First Branch

• Congress is bicameral: consisting of two

chambers.

• Upper is the Senate; Lower is the House

of Representatives.

• They have roughly equal powers.

• Supported by staffs and other institutions.

– Library of Congress, the General Accounting

Office, Congressional Budget Office.

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004

The Organization of Congress

• The two chambers have evolved to meet

the demands of law making

– Division of labor created the committee

system

– Need to organize large numbers of people to

make decisions led to the party leadership

structure.

– Both are more important in the House.

– Senate is small enough to operate by informal

coordination and negotiation.

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004

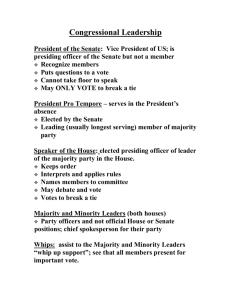

The Congressional Parties:

The House

• Speaker of the House

– The presiding office of the House of Representatives; normally

the Speaker is the leader of the majority party.

• Majority Leader

– Speaker’s chief lieutenant in the House and the most important

officer in the Senate. He or she is responsible for managing the

floor.

• Minority Leader

– Leader of the minority party who speaks for the party in dealing

with the majority.

• Whips

– Members of Congress who serve as informational channels

between the leadership and the rank and file, conveying the

leadership’s views and intentions to the members and vice

versa.

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004

The Congressional Parties:

The House

• Party Caucus

– All Democratic members of the House or

Senate. Members in caucus elect the party

leaders, ratify the choice of committee

leaders, and debate party positions on issues.

• Party Conference

– What Republicans call their party caucus.

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004

The Congressional Parties:

The Senate

• Given that the Senate usually includes two

members from each state – an even number –

some tie-breaking mechanism is necessary.

– Constitution provides the vice-president with authority

to preside over the Senate and to cast a tie-breaking

vote when necessary.

– President pro-tempore serves as Senate presiding

officer in the vice-president’s absence (which is nearly

all the time).

• Ordinarily goes to the most senior member of the majority

party.

• Honorific.

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004

The Congressional Parties:

The Senate

• Senate leadership has a structure of whips and expert

staff, Senate leaders are not as strong as those in the

House.

• Spend most of their time negotiating compromises.

• Unanimous Consent Agreements

– Agreement that sets forth the terms and conditions according to

which the Senate will consider a bill; these are individually

negotiated by the leadership for each bill.

• Filibuster

– delaying tactic- either speaking indefinitely or by offering dilatory

motions and amendments.

• Cloture

– motion to end debate; requires 60 votes to pass.

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004

Ups and Downs of

Congressional Parties

• Difficult to measure the strength of

congressional parties.

– Power of leadership has varied over time.

– Parties more powerful when unified. Leadership

appears more powerful.

– Leadership PACs may help leaders influence

their party members; sense of obligation if

given money.

– Members may accept some party discipline

because it is necessary for attaining policy

goals.

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004

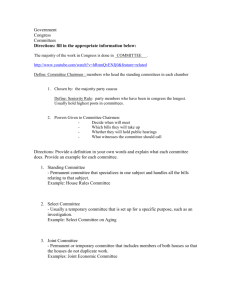

The Committee System

• Since 1989 roughly 6 to 8 thousand bills have

been introduced in each 2 year session in the

House.

• Screening process: division into committees.

– Committees do the work before it comes (if it makes

it) to the floor for a vote.

• Standing committees:

– committee with fixed membership and jurisdiction,

continuing from Congress to Congress.

• Select committees:

– temporary committees appointed to deal with a

specific issue or problem.

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004

House Committees

• Three levels of importance

– Top committees: Rules, Appropriations, Ways and

Means

– Second level: deal with nationally significant policy

areas: agriculture, armed services, civil rights.

– Third level: Housekeeping items. Government Reform

and Oversight or a narrow policy venue such as

Veteran’s affairs.

– Members rarely serve on more than one top

committee.

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004

Senate Committees

• Senate committee system is simpler than that of the

House.

– Has only major and minor committees

– Appropriations and Finance are major committees as are Budget

and Foreign Relations.

• Committee power in the Senate is widely distributed.

– Each senator can serve on one minor and two major

committees, and every senator gets to serve on one of the four

major committees.

– Senators less likely to specialize

– Serve diverse constituencies within an entire state – cannot

afford to limit themselves to one or two subjects.

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004

How Committees Are Formed

• Committee system is formally under the control of the

majority party in the chamber.

• Each committee has a ratio of majority to minority

members at least as favorable to the majority as is the

overall division of the chamber.

• More important the committee, the more likely it is

stacked in favor of the majority.

• Seniority

– Practice by which the majority party member with the longest

continuous service on a committee becomes the chair.

– Has been weakened and reformed.

– Ex: Republican conference adopted a three-term limit on

committee chairs which they enforced in 2000. Enforced by

Senate Republicans in 1996.

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004

Committee Reforms

• 1970s saw much reform of committees by

Democratic caucus.

– Curbed power of standing committee chairs

– Injected more democracy into the committee

system

• Limited House committee chairs to holding one

subcommittee chair

• Subcommittee bill of rights

• Spread power more evening across

subcommittees

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004

Purpose of Committees

• Why do standing committees exist?

– Use committee system to focus on district

interests.

• Logrolling

– Colloquial term given to politicians’ trading of favors,

votes, or generalized support for each other’s proposals.

– Committees serve knowledge function.

– Committees are the tools of congressional

parties.

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004

Caucuses

• Caucuses are groups within Congress formed

by members to pursue common interests.

–

–

–

–

300 such groups in the 108th Congress

Congressional Black Caucus

Northeast-Midwest Congressional Coalition

Sportsmen’s Caucus (funded by NRA and sporting

industry)

• May be increasingly important actors in the

congressional process.

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004

How A Bill Becomes a Law

• Bill or resolution is introduced by a

congressional sponsor and one or more

co-sponsors.

• House Speaker or Senate presiding

officer, advised by chambers

parliamentarian, refers the proposal to the

appropriate committee.

– Multiple referral: said to occur when party

leaders give more than one committee

responsibility for considering a bill.

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004

How A Bill Becomes a Law

• Once a bill goes to committee, the chair gives it

to the appropriate subcommittee.

– Real work begins here.

• If subcommittee takes bill seriously it will:

– Schedule hearings

– After hearings, markup takes place

• Revising it, adding and deleting sections, preparing it for

report to the full committee.

– Full committee may repeat the process, or it may

largely accept the work of the subcommittee.

– If supported, the bill is nearly ready to be reported to

the floor.

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004

How A Bill Becomes a Law

• The chambers diverge in their process at

this point.

• In the House, bills that are not

controversial can be called up and passed

unanimously with little debate.

• Somewhat more important bills

– Fastrack through suspension of the rules

• Here debates is limited to 40 minute, no

amendments are in order, and a two-thirds majority

is required for passage.

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004

How A Bill Becomes a Law

• In the House, legislation that is especially

important goes to the Rules Committee

before going to the floor.

– Rule: specifies the terms and conditions

under which a bill or resolution will be

considered on the floor of the House.

– If the Rules Committee recommends a rule,

the floor then chooses to accept or reject it.

– Usually accepted as the Rules Committee

anticipates what the floor will tolerate.

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004

How A Bill Becomes a Law

• The Senate procedure is a bit simpler.

– For uncontroversial legislation, a motion to

pass a bill by unanimous consent is all that is

necessary.

– More important and controversial legislation

requires the committee and party leaders to

negotiate unanimous-consent agreements.

• Complicated bargains analogous to the rules

granted by the House Rules Committee.

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004

How A Bill Becomes a Law

• So what happens if a majority in one

chamber accepts the bill?

• Nothing. A bill must pass BOTH chambers

in identical form.

• Unless one chamber is willing to defer to

the other, the two must iron out their

differences.

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004

How A Bill Becomes a Law

• Usual method is a conference committee: here a

group of representatives from both the House

and the Senate work to create a compromise

version.

– If they can resolve differences, which they usually do,

the bill goes back to each chamber for a vote.

– If the chambers pass the bill, it will then go to the

president for his action. If it passes, is the process

over?

– Authorization process is over, but appropriations

process may be necessary.

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004

Evaluating Congress:

Criticisms

• The congressional process is lengthy and

inefficient.

• The congressional process works to the

advantage of policy minorities, especially those

content with the status quo.

• Members of Congress are constantly tempted to

use their positions to extract constituency

benefits, even when important national

legislation is at stake.

• Sometimes, the very process of passing

legislation ensures that it will not work.

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004

Why Americans Like Their Members of

Congress More than Congress Itself

• Congress as a whole suffers from a negative

public image.

– Irony: it is the national government’s most electorally

sensitive institution.

– Puzzle: why are members of Congress elected at

such a high rate if we are so critical of the institution?

– Answer: Americans judge their own representatives

by different standards from those which they judge

the collective Congress.

– Public says they prefer a trustee but demand that

their own representative serve them as a delegate.

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004

Reforming Congress:

Limit Their Terms?

• In the 1990s reform movements proposing term

limits swept the country.

• In 1997, 21 states had limited the terms of their

state legislators.

• 23 states also tried to limit their congressional

members’ terms.

• U.S. v. Thornton (1995) ruled such attempts

were unconstitutional.

• Most believe term limits would accomplish little

and potentially do harm.

Pearson-Longman copyright 2004