Chapter 3 - Assessment of Posture

advertisement

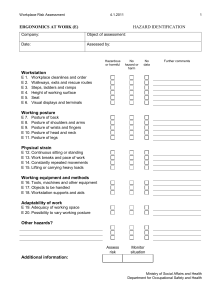

Chapter 3 Assessment of Posture Introduction Posture is the position of the body at a given point in time Correct posture can: – improve performance – decrease abnormal stresses – reduce the development of pathological conditions Introduction Faulty posture: – Deviates from ideal posture – Requires an increased amount of muscular activity – Places an increased amount of stress on the joints and surrounding tissues Restrictions in normal movement patterns may cause compensatory postures – Overtime can result in muscle imbalances and soft tissue dysfunction Introduction Pain related to postural deviations is a common clinical occurrence – Many do not seek help until pain is experienced Postural assessment is used to determine if postural deviations are contributing factors in patient’s pain or dysfunction Posture must be evaluated in functional and nonfunctional positions Clinical Anatomy Musculoskeletal system is designed to function in a mechanically and physiologically efficient manner to use the least possible amount of energy Postural deviations or skeletal malalignment cause other joints in kinetic chain to undergo compensatory motions or postures to allow body to move as efficiently as possible The Kinetic Chain Closed kinetic chain – – – – Weight-bearing Lower extremity Distal segment meets resistance or is fixated Interdependency of each joint = predictable changes in position – Figure 3-1A, page 53 Open kinetic chain – Non-weight-bearing – Upper extremity – Distal segment moves freely in space The Kinetic Chain A dysfunction occurring in one area may affect the proximal or distal associated joints and soft tissue structures – Causing a specific postural deviation The body compensates for these deviations to maintain as much efficiency as possible in movement and function Table 3-1, page 54 Muscular Function Muscles produce joint motion and provide dynamic joint stability Muscles must be of adequate length and function in a proper manner – If too short or too long Adverse stress on joints Work inefficiently Create need for compensatory motions Table 3-2, page 55 Muscular Length-Tension Relationships Describes how a muscle is capable of producing different amounts of tension (force), depending on its length Active insufficiency – Muscle is shortened and maximum tension cannot be produced Passive insufficiency – Muscle is lengthened and cannot generate sufficient tension to be effective Figure 3-4, page 56 Agonist and Antagonist Relationships Agonist – Muscle that contracts to perform the primary movement of a joint Antagonist – Performs opposite movement of agonist and must relax to allow agonist’s motion to occur – Reciprocal inhibition Bicep/triceps example Co-contraction – Used for dynamic stability of joint Muscular Imbalances Impaired relationship between a muscle that is overactivated, subsequently shortened and tightened and another that is inhibited and weakened – Table 3-3, page 57 Postural vs. phasic muscles – Table 3-4, page 57 – Table 3-5, page 57 Soft Tissue Imbalances Joint’s capsule and surrounding ligaments undergo adaptive changes from prolonged overstressing or understressing of structure Faulty posture can alter the position of joints, causing an increase in stress on different portions of the joint capsule and surrounding ligaments Clinical Evaluation of Posture Not an exact science – Radiographs, photographs, computer analysis – Clinical tools – plumb lines, goniometers, flexible rulers, inclinometers (fig. 3-5, page 58) Subjective vs. objective methods – Normal, mild, moderate, severe posture – Quantifiable measurements can assess treatment plan Clinical Evaluation of Posture Commonly assessed in various positions – Standing and sitting – Sport-specific and ADLs Orthoposition – Normal or properly aligned posture – 4 movements to perform before assessment Page 58 History To determine if a postural dysfunction is contributing to the patient’s pathology Identify any routine repetitive motions IF injury is chronic – Explore day to day tasks and posture If injury is acute – Determine factors that may have predisposed athlete to the injury History Mechanism of injury – Common responses Insidious onset Pain worsening as day progresses Posture-specific pain Intermittent, vague , or generalized pain Starting as an ache and progressing Type, location, and severity of symptoms Side of dominance Activities of daily living – Table 3-7, pages 60-61 History Driving, sitting, and sleeping postures – Table 3-8, page 62 Specific postures causing discomfort Level and intensity of exercise Medical History Inspection Considerations – Area being used is private, comfortable – Patient preparedness – Do not inform patient you are assessing posture – Use systematic approach Start at feet and work superiorly or vice versa – Compare bilaterally for symmetry – Your eyes should be at level of region you are observing Overall Impression Determine patient’s general body type – Ectomorph, mesomorph, endomorph – Inherited – Can indicate a person’s natural abilities and disabilities – Does not necessarily dictate how they may function – Box 3-1, page 64 Views of Postural Inspection Inspect from lateral, anterior, posterior views Plumb line – Feet as permanent landmark – Lateral view Slightly anterior to lateral malleolus – Anterior and posterior view Equidistant from both feet – Box 3-2, page 65 Views Lateral view – Table 3-9, page 63 Anterior view – Table 3-10, page 66 Posterior view – Table 3-11, page 67 Inspection of Leg Length Discrepancy Three categories – Structural (true) – Functional (apparent) – Compensatory – Table 3-12, page 68 Block method (Box 3-3, page 69) Figure 3-6, page 68 Figure 3-7, page 70 Figure 3-8, page 70 Palpation To determine specific positions (key landmarks) not necessarily for point tenderness Lateral aspect – Pelvic position ASIS and PSIS, 9-100 Box 3-4, page 71 Palpation Anterior aspect – Patellar position – Iliac crest heights Figure 3-9, page 70 – ASIS heights Figure 3-10, page 70 – Lateral malleolus and fibula head heights – Shoulder heights Figure 3-11, page 72 Palpation Posterior aspect – Many of same landmarks used for anterior view – PSIS position Figure 3-12, page 72 – Spinal alignment – Scapular position Box 3-5, page 73 Not important at this time Common Postural Deviations Not all postural deviations cause pathology Clinicians must identify – Normal posture – Asymptomatic deviations – Deviations causing dysfunction and/or pain Potential muscle imbalances can cause poor posture OR be a result of poor posture Deviations also caused by skeletal malalignment, anomalies, or combination Foot and Ankle Hyperpronation – Review chapter 4 – Figure 3-13, page 74 Supination – Review chapter 4 The Knee Genu Recurvatum – Knee axis of motion is posterior to plumb line – Box 3-6, page 75 Genu Valgum – Occurs due to structural anomalies or muscular weaknesses at the hip Secondary to hyperpronation of the feet – Can lead to Increased pronation Internal tibial and femoral rotation Medial patellar positioning The Knee Genu Varum – Occurs due to Structural anomalies at the hip Excessive supination – Can lead to Supination External tibial and femoral rotation Lateral patellar positioning Interrelationships Between Regions Table 3-14, page 83 May be impossible to determine if posture is the cause or the effect – Understand relationships and importance of correcting the factors involved Most soft tissue dysfunctions that have a gradual, insidious onset have, at least, a minimal postural component Documentation of Postural Assessment Table 3-15, page 85 – As part of a SOAP note Figure 3-14, page 84 – Standard postural assessment form Guidelines for documenting posture – Pages 83, 85