Abstract - Sacramento - The California State University

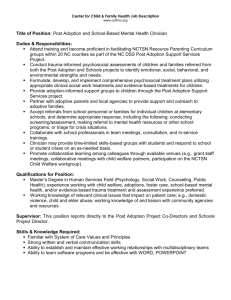

advertisement