Baseline evaluation report

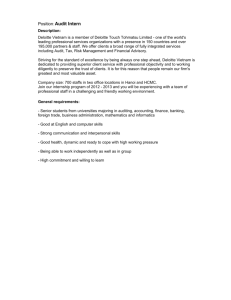

advertisement