The USA, 1919-41 Depth Study

advertisement

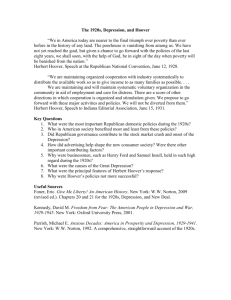

Cambridge ICGSE History Depth Study: The USA, 1919-41 How far did the US economy boom in the 1920s? A New Era Warren Harding: “At the moment, we are on the threshold of a new era.” Henry Ford: “We are entering a new era. Our new thinking and new doing are bringing us a new world, and a new heaven, and a new earth, for which prophets have been looking from time immemorial.” Herbert Hoover: “Our country has entered upon an entirely new era.” Herbert Hoover Warren Harding Henry Ford The Gospel of Scientific Management Scientific management In 1914, Henry Ford successfully was institutionalized in installed a moving assembly line in his a Taylor Society in 1911. Highland Park plant outside Detroit which reduced the time needed to assemble a car from twelve hours to ninety-three minutes. Frederick W. Taylor Assembly Line Ford’s Highland Park Plant Ford’s Philosophy The souls of workers are saved by forcing them to accept the discipline of the assembly line. Workers try to escape from the naturalness of work through the unnaturalness of their imaginations. But the application of Taylor’s time and motion studies to the workday allows the worker no free time for daydreaming. The wellorganized factory keeps the employee busy every moment. “The natural thing to do is work. Human ills flow largely from attempting to escape the natural course. The day’s work is a great thing—a very great thing! Work is our sanity, our self-respect, our salvation…. The net result is the reduction of the necessity for thought on the part of the worker and the reduction of his movements to a minimum. The most beautiful things in the world are those from which all excess has been eliminated. We must cut out useless parts and simplify necessary ones.”—Henry Ford Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936) System: Modern Business Management The significant new magazine of the 1920s was System, dedicated to helping business accept rational leadership. In System, AT&T President Walter Gifford explained “new conditions have called a new type of man to lead the new kind of business organization. These men must take a long view ahead because the company is going to be in business long after they are dead.” The new statesmen of industry were to be the kind of leader exemplified by Herbert Hoover; they were to be men with “greater reverence for scientific method than for the traditions of their class.” AT&T President Walter Gifford in New York (left) watches the moving image of Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover (right) in Washington, D.C., during the first demonstration of television transmission in the United States, 7 April 1927. Business Productivity Productivity increased dramatically from 1920 to 1928. Cars, refrigerators, telephones, and radios became a part of the lives of most Americans. All limits on human experience seemed to have been broken by the productive capacity of the assembly line. “The man who builds a factory builds a temple, and the man who works there worships there. We have seen the people of America create a new heaven and a new earth.” —Calvin Coolidge Assembly Line in a Radio Factory (1925) “The almost unbelievable magic of industry during the truly incredible decade just past has been so continuously amazing as to lead the mere inexpert bystander to be ready for almost anything in the field of material achievement.” —Herbert Hoover “We are a happy people—the statistics prove it. Billboard along US Highway 99 We have more (California, 1937) cars, more Corporate profits increased at least 60 percent bathtubs, oil in the 1920s as industrial production increased furnaces, silk 40 percent. The national government reduced stockings, bank its debt from $24 billion to $16 billion between accounts than any 1920 and 1930. With surpluses flowing into the other people on national treasury, income, estate, and gift taxes earth.” for the rich were reduced in 1926. —Herbert Hoover Economic Boom There were 9 million cars in 1919; by 1929, there were 26 million cars. There were 60 thousand radios in 1920; by 1929, there were 10 million radios. In 1915, there were 10 million telephones; by 1930, there were 20 million telephones. There was more building done during the boom years of the 1920s than at any other time in the history of the US. During the 1920s, the total extent of roads doubled in the US. In 1918, only a few homes had electricity; by 1929, almost all urban homes had electricity. In 1919, there were 1 million trucks; by 1929, there were 3.5 million trucks. In 1900, 12,000 silk stockings were sold; 300 million rayon stockings were sold in 1930. For every 1 refrigerator in 1921, in 1929, there were 167 refrigerators. The car made it possible for more Americans to live in their own houses in the suburbs on the edge of towns. For example, Queens outside New York doubled in size in the 1920s, and Grosse Point Park outside Detroit grew by 700 percent. There were no civilian airlines in 1918; by 1930, the new aircraft companies flew 162,000 flights a year. Farm Productivity Farmers were encouraged to join associations in the way that large corporations did through their trade associations. What proved easy for corporate producers of cars and steel proved impossible for the hundreds of thousands of farmers who produced cotton or wheat or corn. They kept competing with one another, trying to produce more, and continued to Scientific American drive the price of their crops down. A new (10 January 1920) breakthrough in farm mechanization caused by the introduction of the gasoline-powered tractor also increased farm productivity. Increased production resulted in farm income dropping from $22 billion in 1919 to $8 billion in 1928, and by 1933, to $3 billion. This economic downslide forced 6 million rural Americans off their land in the 1920s. These unskilled workers migrated into cities, where there was little demand for their labor. Unemployment and Poverty Most immigration was cut off by legislation in 1921 and 1924 and the birthrate declined, but unemployment persisted throughout the 1920s. With only a 10 percent increase in average wages for the decade, most city dwellers could not afford new housing, so there was significant unemployment in the construction industry. The dynamic rate of growth in radios, refrigerators, and cars leveled off by 1928. An estimated 42 percent of Americans lived below the poverty line, without the money needed to pay for essentials or luxury consumer goods. Representatives attending the 1921 Conference on Unemployment held in Washington, D.C. Advertising and Credit Increasingly, the new consumer economy depended upon advertising to create demand for the products of the assembly line and for credit to make it possible for low income people to indulge these cultivated desires. In 1914, $250 million was spent on advertising in magazines. This figure doubled by 1919 and reached $3 billion by 1929. The mass magazines — Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s, Ladies’ Home Journal, Woman’s Home Companion — no longer considered their readers, as had the nineteenth-century magazines, to be patrons of literature or citizens to be enlightened. Rather they approached their readers as a great market of consumers. Consumer Debt and Speculation Consumers incurred $5 billion of time-payment debt by 1929. Floor of the New York Stock Exchange (c. August 1929) But the upper classes, profiting the most from the prosperity of the 1920s, went furthest into debt. They gambled on the unlimited nature of the stock market. In 1924, the average of industrial stocks was 106; by 1927, it rose to 245. Banks and insurance companies increased their loans to people investing in the market from $1 billion in 1924 to $9 billion in 1929. By the summer of 1929, the market had reached 449, driven up by the frenzy of investment. A Debtor to Creditor Nation The United States had been a debtor nation in 1914, having borrowed money from Europe to develop its industrial potential. By 1920, however, this position was reversed, and European nations owed the United States $10 billion. American bankers continued to lend money in Europe, especially Germany, keeping the European economy, which had been badly weakened by World War I, from collapsing. American bankers also moved to replace European investment in Latin America and Asia, and the world owed American investors more than $20 billion by 1929. Business and political leaders stressed the soundness of an independent American economy, but they also emphasized the need for American business to expand overseas if it was to remain healthy. The Republican Presidents of the 1920s Within the political context of corporate growth and confidence, the Republican party at its convention in 1920 choose an obvious nonleader, Warren G. Harding, for its presidential candidate. Harding and the other Republican Presidents of the 1920s—Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover— symbolized the confidence of the corporate leaders that direct political power was no longer necessary to protect the marketplace from its domestic or international enemies. Republican Campaign Poster (1920) Republican Campaign Poster (1928) Herbert Hoover The son of an Iowa blacksmith, Herbert Hoover had become a multimillionaire by 1914, developing his talents first as a mining engineer in Africa, Asia, and Europe and then as a shrewd investor and administrator of his international business interests. As Secretary of Commerce under Harding and Coolidge, Hoover worked energetically to persuade large corporations to cooperate in trade associations. The three or four companies that dominated each of the areas of major production such as autos, steel, and rubber could plan their futures methodically if they would agree to share the market, fix wages, and set prices. With such coordination, Hoover was certain that the nation had forever left business cycles behind. Within the framework of the corporation, the assembly line would streamline production and distribute an unceasing flow of goods for American consumers. Elected President in 1928, it was believed that Hoover would bring the rationality of the business world to the irrational world of politics. The “Farm Bloc” Opposition The only challenge to the political domination of the corporation came from within the Republican party itself. Senators like LaFollette of Wisconsin, Norris of Nebraska, Borah of Idaho, and Johnson of California cooperated in the establishment of a “farm bloc” that was critical of “monopoly” capitalism while calling for government support of farmers caught in a deteriorating economic situation. In Congress, the “farm bloc” passed the McNary-Haugen plan by which the government would buy surplus farm crops to sell, if need be, at a loss on world markets. But President Coolidge successfully vetoed this legislation in 1927 and in 1928. “Unanimous Verdict,” Sheboygan Press (Sheboygan, Wisconsin, 1925) published after the death of Senator Robert LaFollete, Sr. (R-WI). US Foreign Policy in the 1920s Harding’s Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes and Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover shaped foreign policy. They rejected participation in Woodrow Wilson’s League of Nations because they feared that political commitments might introduce irrational and unpredictable elements into the world marketplace, but they shared Wilson’s desire to contain radicalism and to stabilize the world by expanding the American economy into foreign markets. They believed this expansion would preserve the political order of the rest of the world and at the same time benefit the American economy because “the vast increase in the surpluses of manufactured goods must find a market outside the United States.” Herbert Hoover and Charles Evans Hughes Republican leaders moved vigorously to use American influence to stabilize Europe and Asia. To restore the economic health of the Western European nations and contain Communism, they advocated the restoration of the German economy. They encouraged American bankers to make large loans to Germany and pressured England and France to reduce the reparations they were demanding of Germany. In addition to the Dawes Plan of 1924 and the Young Plan of 1929 designed to accomplish these economic goals, American foreign-policy makers urged the Western European nations to guarantee their mutual borders in the Locarno Pact of 1925. The treaty significantly left the borders of Eastern Europe without guarantees in the hope that the Soviet Union might be reduced in size. At the Washington Conference of 1921, Japan, England, and France agreed to guarantee the political status quo in East Asia, to allow China to be developed under the philosophy of the Open Door, and to stop an arms race by limiting the size of each nation’s navy. OPEN HOUSE Emissary from Washington. “I HAVE COME TO INFORM YOU THAT THE POWERS IN CONFERENCE INSIST ON YOUR BEING MASTER IN YOUR OWN HOUSE; AND IN ORDER THAT THEY MAY SECURE THIS OBJECT THEY REQUIRE YOU TO PROVIDE EACH OF THEM WITH A LATCH-KEY.” China. “HONOURABLE CONFERENCE IS TOO KIND TO CONTEMPTIBLE WORM.” —Punch, 30 November 1921 The Japanese Invasion of Manchuria Soon after Hoover took office in 1929, he faced a major threat to his ideal of a rational market. Imperial Japan, heedless of American plans, moved troops into the northern Chinese province of Manchuria in 1931. But Hoover refused to use military power to check this Japanese expansion. A WORD FROM THE WEST John Bull and Uncle Sam (to Japan). “WHILE ADMITTING THAT THE PROVOCATION TO HONOURABLE FEELINGS MAY HAVE BEEN ALMOST UNBEARABLE, WE VENTURE TO SUBMIT THAT HONOURABLE RETALIATION HAS SHOCKED WESTERN HUMANITY.” —Punch, 10 February 1932 An important reason for his refusal was his fear of the Soviet Union. Hoover, like other American business leaders, had been terrified by the success of the Bolshevik revolution. The United States had managed to contain the revolution within Russian borders, keeping it from spreading in Germany and destroying it where it had gained a foothold in countries like Hungary. Hoover had decided during the 1920s that World War I had been a civil war in which the European capitalist nations had destroyed one another. This anarchy and self-destruction by the supposedly reasonable middle classes had allowed Russia to fall into Communist hands. What would happen if another such civil war, comparable to World War I, broke out among the capitalist nations? Would such conflict provide an environment for another rapid spread of Communist influence? Hoover feared such an outcome. The Fordney-McCumber Act The history of the tariff during the 1920s became a classic example of how Americans tried to have everything and ended up with almost nothing. In 1922, the Fordney-McCumber Act raised tariff walls around American producers, who loudly demanded protection from cheap foreign goods. This act made little sense. Europeans could not repay their debts if they could not sell their goods in the rich US market. The Hoover-Hughes policy of gently guiding the world into a happier, freer-market economy was in shambles by 1928. The two men had been unable to control President Calvin Coolidge and Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon. Editorial Cartoon on the Emergency Tariff of 1921 Prosperity and Fun • The standard picture of the twenties is as a time of prosperity and fun: the Jazz Age, the Roaring Twenties. • Unemployment fell from 4,270,000 in 1921 to a little over 2 million in 1927. • The general level of wages for workers rose; some farmers made a lot of money. • With incomes of more than $2,000 a year, 40 percent of American families could buy automobiles, radios, and refrigerators. • Millions of people were not doing badly, and they could shut out of the picture the others without work or not making enough to get basic necessities: the tenant farmers, black and white, and the immigrant families in the big cities. An American Family (c. 1925) Prosperity at the Top Per Capita Increase Per Annum (1922 to 1928) 20% Real Wages in Manufacturing (+1.4%) Income of Holders of Common Stock (+16.4%) 10% 0% Annual Income of American Families < $1,000 (6 million families) > $1,000 (8 million families) Total Income of Top 1/10th of 1% (14 thousand families) = Total Income of Bottom 42% (6 million families) An Italian American Family in a New York Tenement (c. 1920) Two million workers in New York City lived in tenements condemned as firetraps. Every year in the 1920s, about 25,000 workers were killed on the job and 100,000 permanently disabled. Burial Service for the 171 Miners Killed in the Castle Gate Mine Explosion (Utah, 1924) The Middletown Studies In the 1920s, the US was full of little industrial towns like Muncie, Indiana, where, according to sociologists Robert and Helen Lynd, the class system was revealed by the time people got up in the morning: for two-thirds of the city’s families, “the father gets up in the dark in winter, A 1921 Postcard of Muncie, Indiana eats hastily in the kitchen in the gray dawn, and is at work from an hour to two and a quarter hours before his children have to be at school.” The “Mellon Plan” One of the richest men in America was Andrew Mellon, Secretary of the Treasury (1921-1932) during the presidencies of Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover. In 1923, Congress passed the “Mellon Plan,” lowering the tax rate on the top income brackets from 50 percent to 25 percent and on the lowestincome group from 4 percent to 3 percent. “I am not going to have my people who work in the shoe factories of Lynn and in the mills of Lawrence and the leather industry of Peabody, in these days of so-called Republican prosperity when they are working but three days in the week think that I am in accord with the provisions of this bill…. When I see a provision in the Mellon tax bill which is going to save Mr. Mellon himself $800,000 on his income tax and his brother $600,000 on his, I cannot give it my support.” —Rep. William P. Connery, Jr. (D-MA) Rep. Fiorello La Guardia (R-NY) Few political figures spoke out for the poor of the twenties. One was Fiorello La Guardia, a Congressman from a district of poor immigrants in East Harlem (who ran, oddly, on both Socialist and Republican tickets). In 1928, La Guardia toured the poorer districts of New York and said: “I confess I was not prepared for what I actually saw. It seemed almost incredible that such conditions of poverty could really exist.” Fiorello La Guardia La Guardia was made aware by people in his district of the high price of meat. When he asked Secretary of Agriculture William Jardine to investigate, the Secretary sent him a pamphlet on how to use meat economically. La Guardia wrote back: Holcomb and Hoke’s Cooling Glass Meat Cases and Freezer Counters (introduced in 1921) “I asked for help and you send me a bulletin. The people of New York City cannot feed their children on department bulletins…. Your bulletins … are of no use to the tenement dwellers of this great city. The housewives of New York have been trained by hard experience on the economical use of meat. What we want is the help of your department on the meat profiteers who are keeping the hard-working people of this city from obtaining proper nourishment.” Coal Miners Strike (1922) In 1922, coal miners and railroad men went on strike, and Senator Burton Wheeler (D-MT), a Progressive elected with labor votes, visited the strike area and reported: Miners Going on Strike in Scranton, Pennsylvania (31 March 1922) “All day long I have listened to heartrending stories of women evicted from their homes by the coal companies. I heard pitiful pleas of little children crying for bread. I stood aghast as I heard most amazing stories from men brutally beaten by private policemen. It has been a shocking and nerveracking experience.” Textile Strike (1922) A textile strike in Rhode Island in 1922 among Greek, Irish, Italian Polish, and Portuguese workers failed, but class feelings were awakened and some of the strikers joined radical movements. Luigi Nardella recalled: “My oldest brother, Guido,…started the strike…. When the strike started we didn’t have any union organizers…. Somebody from the Young Workers’ League came out…and invited me to a meeting, and I went. Then I joined…. We were anti-fascists. I spoke on street corners…to good crowds. And we led the Funeral of Murdered Textile Striker, Rhode Island (1922) support for Sacco and Vanzetti.” Furriers’ Strike (1926) After the first world war, an American Communist party was organized, and Communists were involved in the organization of the Trade Union Education League, which tried to build a militant spirit inside the American Federation of Labor. When a Communist named Ben Gold, of the furriers’ section of the TUEL, challenged the AFL union leadership at a meeting, he was knifed and beaten. But in 1926, Gold and other Communists organized a strike of New York City furriers who formed mass picket lines, battled police to hold their lines, were arrested and beaten, but kept striking, until they won a forty-hour week and a wage increase. Ben Gold Textile Strike (1929) New England textile mill owners moved their operations to the South to escape unions and to find more subservient workers among poor, Southern whites. But these workers rebelled as well, resisting the long hours and the low pay. Workers particularly resented the intensification of work known as the “stretch-out.” For instance, a weaver who had operated twenty-four looms and got $18.91 a week would be raised to $23.00, but he would be “stretched out” to a hundred looms and had to work at a punishing pace. Loray Mill Strike, Gastonia, North Carolina (1929) The first of the textile strikes was in Tennessee, where five hundred women in one mill walked out in protest against wages of $9.00 to $10.00 a week. Loray Mill Strike, Gastonia, North Carolina (1929) Then at Gastonia, North Carolina, workers joined a new union, the National Textile Workers Union, led by Communists, which admitted both Blacks and whites to membership. When some of them were fired, half of the two thousand workers went out on strike. An atmosphere of anti-Communism and racism built up and violence began. Textile strikes spread across South Carolina. One by one, the various strikes were settled, but not at Gastonia. The Gastonia strikers, living in a tent colony, refused to renounce the Communists in their leadership. The strike went on, but strikebreakers were brought in and the mills kept operating. Desperation grew; there were violent clashes with the police. One dark night, the chief of police was killed in a gun battle. Sixteen strikers and sympathizers were indicted for murder; seven were tried and given sentences from five to twenty years. The children of murdered union supporter Ella Mae Wiggins stand by their mother’s grave (Loray Mill Strike, Gastonia, North Carolina, 1929) Released on bail, they left the state, the Communists escaping to Soviet Russia. Through all the defeats, the beatings, the murders, however, it was the beginning of textile mill unionism in the South. An Unsound Economy Liberal economist John Kenneth Galbraith studied the 1920s, concluding that “the economy was fundamentally unsound.” He pointed to very unhealthy corporate and banking structures, an unsound foreign trade, much economic misinformation, and the “bad distribution of income” (the highest 5 percent of the population received about one-third of all personal income). A socialist critic would go further and say that the capitalist system was by its nature unsound: a system driven by the one overriding motive of corporate profit and therefore unstable, unpredictable, and blind to human needs. The result of all that: permanent depression for many of its people, and periodic crises for almost everybody. Capitalism, despite its attempts at selfreform, its organization for better control, was and is a sick and undependable system. Controlling Information In the 1920s, according to historian Merle Curti, “it was, in fact, only the upper ten percent of the population that enjoyed a marked increase in real income. But the protests which such facts normally have evoked could not make themselves widely or effectively felt. This was in part the result of the grand strategy of the major political parties. In part it was the result of the fact that almost all the chief avenues to mass opinion were now controlled by largescale publishing industries.” First Issue of Time (3 Mar 1923) NBC’s First Logo (15 Nov 1926) “Echoes of the Jazz Age” (1931) “It was borrowed time anyway—the whole upper tenth of a nation living with the insouciance of a grand duc and the casualness of chorus girls…. A classmate killed his wife and himself on Long Island, another tumbled ‘accidentally’ from a skyscraper in Philadelphia, another purposely from a skyscraper in New York. One was killed in a speak-easy in Chicago; another was beaten to death in a speak-easy in New York and crawled home to the Princeton Club to die; still another had his skull crushed by a maniac’s axe in an insane asylum where he was confined.” —F. Scott Fitzgerald F. Scott Fitzgerald Babbitt (1922) “It was the best of nationally advertised and quantitatively produced alarm-clocks, with all modern attachments, including cathedral chime, intermittent alarm, and a phosphorescent dial. Babbitt was proud of being awakened by such a rich device. Socially it was almost as creditable as buying expensive cord tires…. He sulkily admitted now that there was no more escape, but he lay and detested the grind of the real estate business, and disliked his family, and disliked himself for disliking them.”—Sinclair Lewis Babbitt by Sinclair Lewis Summary oOn what factors was the economic boom based? • The owners of US corporations dominated politics to the benefit of industry. • Tariffs were raised to protect US industries from foreign competition. • Taxes were lowered to benefit the rich. • Republican leaders encouraged corporations to collude to form monopolies. • Radicals were deported, and labor was controlled by force. • European economies were devastated by World War I, and the US emerged from the war as a creditor nation. • New methods of scientific management and the assembly line increased productivity. • Advertising and purchasing on credit or installment buying created demand for consumer goods. oWhy did some industries prosper while others did not? • The development of new man-made materials competed with older industries. For example, rayon replaced silk in women’s stockings, and the use of electricity limited the use of coal. oWhy did agriculture not share in the prosperity? • Overproduction in the agricultural sector drove down prices. oDid all Americans benefit from the boom? • No, only about 10 percent of Americans benefited from the boom. Rises in productivity primarily benefited the owning class. oHow did the development of credit and hire purchases contribute to economic expansion? • The development of credit and hire purchases allowed more Americans to buy luxury consumer goods. oHow did mass production in industries for cars and consumer durables contribute to economic expansion? • Mass production increased demand for inputs and lowered prices just enough for Americans to become consumers. oWhat were the fortunes of older industries in the 1920s? • The older industries, coal and textile, were hit with strikes. oHow and why did agriculture decline in the 1920s? • Overproduction in the agricultural sector drove down prices, forcing six million farmers off their land. oWhat were the weaknesses in the economy by the late 1920s? • Unemployment and poverty rates were high, limiting the consumption-led economy. Labor was kept down by force. • Only the top 10 percent benefited from the economic boom, and most of the benefit went to the top 1/10 of 1 percent. • Speculation and debt created economic instability. • The agricultural sector was devastated; farmers driven from their land could not find employment as the new industries, relying on productivity improvements, did not create jobs. • Work without thought for the purpose of consumption does not meet human needs. • American businesses needed international markets, but high tariffs hurt the global economy.