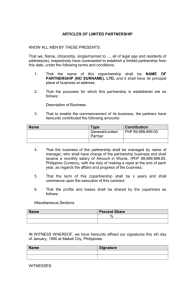

Proposal succeeds. Province is divided (S).

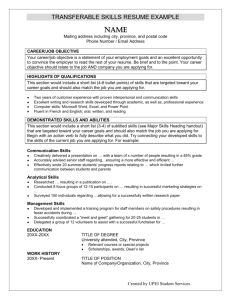

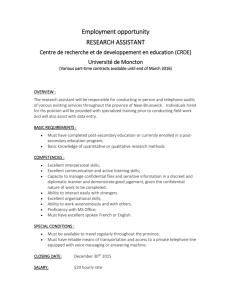

advertisement