Day 2_Session 3 - Short Term Long Term Budgeting

advertisement

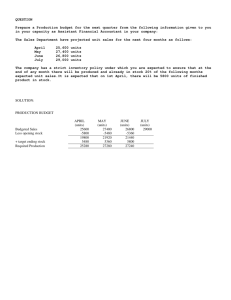

SHORT- AND LONG-TERM BUDGETING (PLANNING AND MONITORING) Financed by Financed by Supported by Supported by Implemented in cooperation with Implemented in cooperation with WHAT IS A BUDGET? A budget is a detailed plan of actions for a future period expressed in numbers Forward-looking, but often in consideration of historical patterns Financed by Supported by Implemented in cooperation with WHY BUDGETING? Any small business owner intent on planning a successful future for his or her business must take into account how to fund that plan. Put simply, maintaining a good short- and long-term financial plan enables you to control your cash flow instead of having it control you. 1. Budgeting forces management to plan for the future—to develop an overall direction for the organization, foresee problems, and develop future policies. 2. Budgeting helps convey significant information about the resource capabilities of an organization, making better decisions possible. Example: A cash budget points out potential shortfalls. 3. Budgeting helps set standards that can control the use of a company’s resources and control and motivate employees. 4. Budgeting improves the communication of the plans of the organization to each employee. Budgets also encourage coordination because the various areas and activities of the organization must all work together to achieve the stated objectives. Financed by Supported by Implemented in cooperation with CLASSIFICATION OF BUDGET BY TIME Short-term Budgeting prepared for a period of one year or less divided into quarterly or monthly budgets typically for continuing operations Example: master budget, operational budgets, cash budget Financed by Supported by Long-term Budgeting prepared for longer than one year, normally for a period of 5 to 10 years generally for assets and projects Example: Capital budget, research and development budget, long term finances etc. Implemented in cooperation with MASTER BUDGET The master budget has two components, the operating budget and the financial budget. The operating budget focuses on the budgets that produce income, translating into a budgeted income statement as its outcome. Financial budgets focus on the flow of cash into and out of an organization and produce a cash budget and balance sheet. The diagram below illustrates the relationships between the operating and financial budgets and the products they produce in the end. Financed by Supported by Implemented in cooperation with OPERATING BUDGET The operating budget consists of the following 11 budgets in sequence that covers all income and revenue from organizational operations: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. Sales Budget Production Budget Direct Materials Purchases Budget Direct Labor Budget Overhead Budget Ending Finished Goods Inventory Budget Cost of Goods Sold Budget Marketing Expense Budget Research and Development Budget Administrative Expense Budget 11. Budgeted Income Statement The operating budget’s purpose is to predict an accurate picture of the organization’s expenses so that operations are financed throughout the budget cycle. It is critical to define an accurate sales picture and align it with the appropriate workflow to produce efficient, overall profitable operations. Financed by Supported by Implemented in cooperation with OPERATING BUDGET All operating budgets for a commercial companies follow this structure: Sale / Turnover - Variable costs / used goods = Gross profit - Fixed costs - Depreciation - Interests = Profit Below you can find different types of expenses. Maybe your company does not have all the expenses. Then just delete the expense (the account) in your budget. Maybe you have another expense. Then just put it in the budget. The budget must reflect your company. Sale / Turnover Sale of product / service no. 1 Sale of product / service no. 2 Sale of product /service no. … Estimate sale for each major product /service Interest Write-off/depreciation Interest on bank loan Plant/buildings Interest on overdraft facility Machinery Other interest Other things ... Financed by Supported by Implemented in cooperation with OPERATING BUDGET ...Variable costs Materials - raw materials and finished products which you use for production or sale Salary - only for workers in production Transport costs - and any costs related to transport of the raw materials and finished products Fixed costs Wages - for staff in shops and offices Rent - for buildings Electricity, heat, water Renovation and maintenance of buildings Cleaning Car service/mileage allowance Travel costs Stationary telephone Postage and charges Mobile phone Internet-connection Website subscription/hosting and upgrading Financed by Supported by Marketing/advertisement/advertising Meeting expenses Insurances Computer equipment Computer network Leasing-expenses Minor purchases Maintenance Accountant Lawyer Other consultancy Unexpected costs (5% of costs) Implemented in cooperation with SALES BUDGET • • The sales budget is the most important component of the operating budget. It has to be produced first since other budgets depend on the output. If the sales budget is not as accurate as possible, it will lead to larger discrepancies in the remainder of the operating budgets. usually presented in either a monthly or quarterly format; presenting only annual sales information is too aggregated, and so provides little actionable information. Factors that has to be taken into consideration while preparing: Organizational Environmental factors Past sales figures and trends Salesmen’s estimates Plant capacity Orders on hand Proposed expansion or discontinuation of products Availability of material or supplies Financial aspect Cost of distribution of goods Financed by Supported by General trade prospects Seasonal fluctuations Degree of competition Government controls and rules Sales = Units × Unit selling price Implemented in cooperation with SALES BUDGET - Example ABC Company plans to produce an array of plastic pails during the upcoming budget year, all of which fall into a single product category. Its sales forecast is outlined as follows: Sales Budget - For the Year Ended December 31, 20XX Forecasted unit sales x Price per unit Total gross sales - Sales discounts & allowances = Total net sales Quarter 1 Quarter 2 Quarter 3 Quarter 4 5,500 6,000 7,000 8,000 $10 $10 $11 $11 $55,000 $60,000 $77,000 $88,000 $1,100 $1,200 $1,540 $1,760 $53,900 $58,800 $75,460 $86,240 ABC's sales manager expects that increased demand in the second half of the year will allow it to increase its unit price from $10 to $11. Also, the sales manager expects that the company's historical sales discounts and allowances percentage of two percent of gross sales will continue through the budget period. Financed by Supported by Implemented in cooperation with PRODUCTION BUDGET The production budget takes the output from the sales budget, unit sales, and adds desired ending inventory and then subtracts beginning inventory to obtain the number of units to be produced for each period. Special attention should be paid to planning desired ending inventory, whether a particular number of units are given or decided, or if an inventory rule is to be followed. Lost sales or work stoppages in production can occur if there is not enough ending inventory and excess ending inventory utilizes finances that may be needed elsewhere in the organization. Units to be produced = Ending inventory units + Units sales – Beginning inventory units basic calculation used by the production budget is: + Forecasted unit sales + Planned finished goods ending inventory balance = Total production required - Beginning finished goods inventory = Products to be manufactured Financed by Supported by Implemented in cooperation with PRODUCTION BUDGET - Example Production Budget For the Year Ended December 31, 2009 Budgeted sales 1 Quarter 2 Quarter 3 Quarter 4 Quarter Year 10,000 30,000 40,000 20,000 100,000 8,000 -----------38,000 6,000 -----------32,000 4,000 -----------44,000 8,000 -----------36,000 3,000 ----------23,000 4,000 -----------19,000 3,000 ----------103,000 2,000 -----------101,000 Add desired ending inventory of finished goods* 6,000 -----------Total needs 16,000 Less Beginning inventory of finished goods 2,000 -----------Required production 14,000 *Twenty percent of the next quarters sales. The ending inventory of 3,000 cases is assumed The beginning inventory in each quarter is the same as the prior quarter's ending inventory Mmanagement believes that an ending inventory equal to 20% of the next quarter's sales strikes the appropriate balance. The total needs for the first quarter are determined by adding together the budgeted sales of 10,000 cases for the quarter and the desired ending inventory of 6,000 cases. The ending inventory is intended to provide some cushion in case problems develop in production or sales increase unexpectedly. Since the budgeted sales for the second quarter are 30,000 cases and management would like the ending inventory in each quarter to 20% of the following quarter's sales, the desired ending inventory is 6,000 cases (20% of 30,000 cases). Consequently, the total needs for the first quarter are 16,000 cases. However, since the company already has 2,000 cases in beginning inventory, only 14,000 cases need to be produced in first quarter. Financed by Supported by Implemented in cooperation with DIRECT MATERIALS BUDGET The direct materials purchases budget can be developed once the production budget is complete. The direct materials purchases budget converts the raw materials per unit to a total amount of materials for unit production. Similar to the production budget, desired ending inventory is added to this total amount of materials and beginning inventory is subtracted. This calculation give the total units to be produced for the period and multiplying the cost per unit of material (lbs, gram, ounces, etc) produces the total purchase cost for the period Expected DM usage = DM units needed per unit of output × Units of output Budgeted DM purchases in units = Desired ending DM units + Expected DM usage – Beginning DM units DM purchase costs = Budgeted DM purchases in units × Unit price Financed by Supported by Implemented in cooperation with DIRECT MATERIALS BUDGET - Example Hampton Freeze, Inc. Direct Materials Budget For the Year Ended December 31, 2009 1 Quarter 2 Quarter 3 Quarter 4 Quarter Year Required production in cases 14,000 32,000 36,000 19,000 101,000 Raw materials needed per case (pounds) 15 15 15 15 15 Total needs ----------210,000 48,000 -----------258,000 ----------480,000 54,000 -----------534,000 ----------540,00 28,500 -----------568,500 ----------285,000 22,500 -----------307,500 ----------1,515,000 22,500 -----------1,537,500 Less beginning inventory of raw materials 21,000 48,000 54,000 28,500 21,000 Raw materials to be purchased Cost of raw materials per pound -----------237,000 $0.20 ------------ -----------486,000 $0.20 ------------ -----------514,000 $0.20 ------------ -----------279,000 $0.20 ------------ -----------1,516,500 $0.20 ------------ Cost of raw materials to be purchased $47,400 $97,200 $102,900 55,800 $303,300 Production needs (pounds) Add desired ending inventory of raw material 1 % of purchases paid for in the period of the purchase % of purchase paid for in the period after purchase 50% 50% 50% 50% 1 Ten percent of the next quarter's needs. For example, the second-quarter production needs are 480,000 pounds. Therefore, the desired ending inventory for the first quarter would be 10% 480,000 pounds = 48,000 pounds. The ending inventory of 22,500 pounds for the quarter is assumed Financed by Supported by Implemented in cooperation with DIRECT MATERIALS BUDGET - Example cont. Cont. Hampton Freeze, Inc. Direct Materials Budget For the Year Ended December 31, 2009 Schedule of Expected Cash Disbursement for Materials Accounts payable, beginning balance2 $25,800 First-quarter purchase3 Second-quarter purchases4 23,700 $25,800 $23,700 48,600 Third-quarter purchase5 $48,600 51,450 $51,450 102,900 27,900 ---------$301,200 Fourth-quarter purchase6 Total cash disbursement ---------- --------- ---------- 27,900 ---------- $49,500 $72,300 $100,050 $79,350 2Cash payments for the last year's fourth-quarter materials purchases. × 50%; $47,500 × 50%. × 50%; $97,200 × 50%. 5$102,900 × 50%; $102,900 × 50%. 6$55,800 × 50%. Unpaid fourth quarter's purchases appear as accounts payable on the company's end of year balance sheet 3$47,500 4$97,200 Financed by Supported by 47,400 97,200 Direct materials budget is usually accompanied by a schedule of expected cash disbursements for raw materials. This schedule is needed to prepare the overall cash budget. Disbursement of raw materials consist of payments for purchases on account in prior periods plus any payments for purchases in the current budget period. Implemented in cooperation with DIRECT MATERIALS BUDGET – Example cont. Explanation of the Direct Materials Budget for Hampton Freeze Inc. In this case, management would like to maintain ending inventories of raw materials equal to 10% of the following quarter's production needs. The first line in the direct materials budget contains the required production for each quarter, which is taken directly from the production budget. Looking at the first quarter, since the schedule of production budget calls for the production of 14,000 cases of popsicles (finished goods of Hampton Freeze Inc.) and each case requires 15 pounds of sugar, the total production needs are for 210,000 pounds of sugar (14,000 cases × 15 pounds per case). In addition, management wants to have ending inventories of 48,000 pounds of sugar, which is 10% of the following quarter's needs of 480,000 pounds. Consequently the total needs are for 258,000 pounds (210,000 pounds for the current quarter's production plus 48,000 pounds for the desired ending inventory). However, since the company already has 21,000 pounds in beginning inventory, only 237,000 pounds of sugar (258,000 pounds – 21,000 pounds) will need to be purchased. Finally, the cost of the materials purchases is determined by multiplying the amount of raw materials to be purchased by the cost per unit of the raw materials. In this case, since 237,000 pounds of sugar will have to be purchased during the first quarter and sugar costs $0.20 per pound, the total cost will be $47,400 (237,000 pounds × $0.20 per pound). As with the production budget, the amounts listed under the year column are not always just the sum of the quarterly amounts. The desired ending inventory of raw materials for the year is the same as the desired ending inventory of raw materials for the fourth quarter. Likewise the beginning inventory of the raw materials for the year is the same as the beginning inventory of raw materials for the first quarter. Financed by Supported by Implemented in cooperation with DIRECT LABOR BUDGET The direct labor budget is similar to the direct materials budget as it depends on production output. Multiplying the direct labor cost per unit times the units produced each period produces the direct labor hours needed. Multiplying the total times the direct labor cost per hour provides the total direct labor cost for the period. Expected DL hours = DL hours needed per unit of output × Units of output DL costs = Expected DL hours × Wage rate Example of Direct Labor Budget Hampton Freeze, Inc. Direct Labor Budget For the Year Ended December 31, 2003 Required production in cases Direct labor hours per case Total direct labor hours needed Direct labor cost per hour Total direct labor cost* 1 Quarter 2 Quarter 3 Quarter 4 Quarter Year 14,000 0.40 -------5,600 $15.00 -------- 32,000 0.40 --------12,800 $15.00 -------- 36,000 0.40 -------14,400 $15.00 -------- 19,000 0.40 -------7,600 $15.00 -------- 101,000 0.40 -------40,400 $15.00 -------- $84,000 $192,000 $216,000 $114,000 $606,000 * This schedule assumes that the direct labor work force will be fully adjusted to the total direct labor hours needed each quarter. Financed by Supported by Implemented in cooperation with OVERHEAD BUDGET The overhead budget provides the cost of all non-labor and non-material items used during the production process for each defined period. Total overhead cost is calculated by adding variable and fixed overhead costs. Variable overhead is calculated by multiplying the variable overhead rate times the direct labor hours. Total overhead = (Variable overhead rate × Activity level per chosen cost driver) + Budgeted total fixed overhead Financed by Supported by Implemented in cooperation with OVERHEAD BUDGET – Example Hampton Freeze Inc. Manufacturing Overhead Budget For the Year Ended December 31, 2003 Budgeted direct labor hours Variable overhead rate Variable manufacturing overhead Fixed manufacturing overhead Total manufacturing overhead Less depreciation Cash disbursement for manufacturing overhead Total manufacturing overhead (a) Budgeted direct labor-hours (b) Predetermined overhead rate for the year (a) / (b) 1 Quarter 5,600 $4.00 --------$22,400 60,600 83,000 15,000 $68,000 ======= 2 Quarter 12,800 $4.00 --------$51,200 60,600 111,800 15,000 $96,800 ======= 3 Quarter 14,400 $4.00 --------$57,600 60,600 118,200 15,000 $103,200 ======= 4 Quarter 7,600 $4.00 --------$30,400 60,600 91,000 15,000 $76,000 ======= Year 40,400 $4.00 --------$161,600 242,400 404,000 60,000 $344,000 ======= $404,000 40,400 $10.00 Because the variable component of the manufacturing overhead depends on direct labor, the first line in the manufacturing overhead budget consists of the budgeted direct labor hours from the direct labor budget . The budgeted direct labor hours in each quarter are multiplied by the variable rate to determine the variable component of the manufacturing overhead. For example, the variable manufacturing overhead for the first quarter is $22,400 (5,600 direct labor hours × $4.00 per direct labor-hour). This is added to the fixed manufacturing overhead for the quarter to determine the total manufacturing overhead for the quarter. The total manufacturing overhead for the first quarter is $83,000 ($22,400 + $60,600). Financed by Supported by Implemented in cooperation with ENDING FINISHED GOODS INVENTORY BUDGET Calculating ending finished goods inventory is needed for input for the cost of goods sold budget. Total ending inventory cost is calculated by multiplying the unit cost (direct materials cost per unit, direct labor cost per unit, overhead cost per unit) x the number of units in ending inventory. Financed by It provides information for the unit cost of a finished product and the cost of the expected inventories. Supported by Implemented in cooperation with ENDING FINISHED GOODS INVENTORY BUDGET – Example Freeze Inc. Ending Finished Goods Inventory Budget Absorption Costing Bases For the Year Ended December 31, 2009 Production Cost Per Case: Direct materials Direct labor Manufacturing overhead Unit product cost Budgeted finished goods inventory: Ending finished goods inventory Unit production cost (see above) Ending finished goods inventory in dollars Quantity Cost Total 15 Pounds 0.40 hours 0.40 hours $0.20 per pound 15.00 per hour 10.00 per hour $3.00 6.00 4.00 --------$13.00 3,000 $13.00 ----------$39.00 For Hampton Freeze Inc. the absorption costing unit product cost is $13 per case of popsicles (finished goods of Hampton Freeze Inc.)--costing of $3 of direct materials, $6 of direct labor, and $4 of manufacturing overhead. The manufacturing overhead is applied to units of product on the basis of direct labor-hours at the rate of $10 per direct labor-hour. The budgeted carrying cost of the expected inventory is $39,000. Financed by Supported by Implemented in cooperation with MARKETING EXPENSE BUDGET The marketing expense budget is used to define all costs associated with sales/distribution of an organization’s products. Expenditures can be fixed or variable. Variable marketing expense is calculated by multiplying the unit variable marketing expense times the unit sales. Total marketing expense = (Variable marketing rate × Sales activity level) + Budgeted total fixed marketing expenses Typical general marketing expenses: • Advertising agency commissions • Salaries for marketing managers • Salaries for marketing support e.g. marketing assistants. • Office space • Fixtures and fittings • Travel costs • Other direct and indirect marketing costs, including marketing communications costs Financed by Supported by Typical marketing communications costs: • Personal Selling • Public Relations • Printing & Mailing • Website Development & Hosting • Brochure Design & Advertising • Television Advertising & Radio Advertising • Direct Marketing • Newspaper Advertising • Proposal Development/bid submittal • Networking • Event Attendance • Sales Promotion • Many other marketing communications tools. Implemented in cooperation with ADMINISTRATIVE EXPENSE BUDGET Administrative expenses are not production related and are mostly fixed in nature. Examples include: salaries, legal fees, accounting fees, equipment depreciation, building depreciation, office supplies, travel expenses, insurance, rent, etc. Financed by Supported by Implemented in cooperation with ADMINISTRATIVE EXPENSE BUDGET - Example Freeze Inc. Selling and Administrative Expense Budget For the Year Ended December 31, 2009 Budgeted sales in cases Variable selling and administrative expenses per case Budgeted variable expense Budgeted fixed selling and administrative expenses: Advertising Executive salaries Insurance Property taxes Depreciation Total budgeted fixed selling and administrative exp. Total budgeted selling and administrative expenses Less depreciation Cash disbursements for selling and administrative exp. 1 Quarter 10,000 $1.80 $ 18,000 2 Quarter 30,000 $1.80 $54,000 3 Quarter 40,000 $1.80 $72,000 4 Quarter 20,000 1.80 $36,000 Year 100,000 $1.80 $180,000 20,000 55,000 20,000 55,000 1,900 20,000 55,000 37,750 20,000 55,000 80,000 220,000 39,650 18,150 40,000 397,800 -----------577,800 40,000 $537,800 10,000 85,000 -----------103,000 10,000 $93,000 10,000 86,900 -----------140,900 10,000 $130,900 10,000 122,750 -----------194,750 10,000 $184,750 18,150 10,000 103,150 -----------139,150 10,000 $129,150 In the above example the variable selling and administrative expense is $1.80 per case. Consequently, budgeted sales in cases for each quarter are entered at the top of the schedule. These data are taken from the sales budget. The budgeted variable selling and administrative expenses are determined by multiplying the budgeted sales in cases by the variable selling and administrative expense per case. For example, the budgeted variable selling and administrative expense for the first quarter is $18,000 (10,000 cases × $1.80 per case). The fixed selling and administrative expenses (all given data) are then added to the variable selling and administrative expenses to arrive at the total budgeted selling and administrative expenses. Finally, to determine the cash disbursement for selling and administrative items, total budgeted and administrative expense is adjusted Implemented by adding back non-cash Financed by Supportedselling by in cooperation with selling and administrative expenses (in this case, just depreciation). BUDGETED INCOME STATEMENT Completing the operating budgets above produces the budged income statement. It gives an accurate picture of the profitability of organizational operations and a tool for maximizing operational strengths and reducing deficiencies. Freeze Inc. Budgeted Income Statement For the Year Ended December 31, 2009 Other Budgets References Sales Sales budget $2,000,000 Less cost of goods sold* Sales budget, Ending finished goods inventory budget 1,300,000 -------------- Gross margin 700,000 Less selling and administrative expenses Selling and administrative expense budget 577,800 -------------- Net operating income 122,200 Less interest expense Cash budget 14,000 -------------- Net income Financed by $108,200 Supported by Implemented in cooperation with CASH BUDGET – Financial Budget contains an itemization of the projected sources and uses of cash in a future period. allows the financial manager to identify short-term financial needs and whether company operations and other activities will provide a sufficient amount of cash to meet projected cash requirements. The idea of the cash budget is simple: it records estimates of cash receipts (cash in) and disbursements (cash out). The result is an estimate of the cash surplus or deficit. Cash Inflows: Cash collections = Beginning accounts receivable + Sales Cash Outflows: Total cash disbursements= Payment of accounts + Wages,taxes, and other expenses + Capital Expenditures + Interest and Dividends The Cash Balance: Net cash inflow = Total cash collections - Total cash disbursements Financed by Supported by Implemented in cooperation with CASH BUDGET - Example Everson Manufacturing Week 4 Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 $25,000 $55,000 -$24,000 -$63,000 +10,000 +12,000 +15,000 +18,000 +180,000 +185,000 +180,000 +192,000 +30,000 0 +10,000 +25,000 $245,000 $252,000 $181,000 $172,000 -$87,000 -$91,000 -$99,000 -$107,000 - Direct labor -19,000 -20,000 -23,000 -25,000 - Manufacturing overhead -29,000 -30,000 -34,000 -37,000 - Selling & administrative -35,000 -35,000 -38,000 -38,000 - Asset purchases -20,000 0 -50,000 0 - Dividend payments 0 -100,000 0 0 = Total uses of cash -$190,000 -$276,000 -$244,000 -$207,000 $55,000 -$24,000 -$63,000 -$35,000 Beginning cash Cash Inflow + Cash sales + Accounts receivable collected + Asset sales = Total cash available Cash Outflow - Direct materials Net Cash Position Financed by Supported by Implemented in cooperation with LONG-TERM BUDGETING helpful in business forecasting and forward planning. cover a period of more than one year on a quarterly basis, or even an annual basis. should be updated when the short-term plan is prepared Capital budgeting Research and development budget Financed by Supported by outlines the estimated expenditures of research and development activities for the coming year Implemented in cooperation with CAPITAL BUDGET The process of planning and managing a firm’s long-term investments Preparation of capital budget plans includes forecasting profits of many years in advance so as to judge the profitability of projects. Capital expenditure plans rivet a huge investment in fixed assets. Capital expenditure once approved signifies long-term investment which cannot be withdrawn or reserved without sustaining a loss. The criteria used to evaluate proposed investments: 1. Payback period 2. Net present value (NPV) 3. Internal rate of return (IRR) What services will we offer or what will we sell? In what markets will we compete? What new products will we introduce? The answer to any of these questions will require that the firm commit its scarce and valuable capital to certain types of assets. Financed by Supported by Implemented in cooperation with CAPITAL BUDGET Payback period: represents the amount of time that it takes for a project to recover its initial cost. The use of the Payback Period as a Capital Budgeting decision rule specifies that all independent projects with a Payback Period less than a specified number of years should be accepted. Paypack = Period Last year with a negative NCF + (Absolute Value of NCF in that year) (total cash flow in the following year) Example: Financed by Year Cash Flow Net Cash Flow 0 -1000 -1000 1 500 -500 2 400 -100 3 200 100 4 200 300 5 100 400 Supported by Payback Period = 2 + (100)/(200) = 2.5 years Implemented in cooperation with CAPITAL BUDGET The Net Present Value (NPV): indicates the expected impact of the project on the value of the firm. The NPV decision rule specifies that all independent projects with a positive NPV should be accepted. where CFt = the cash flow at time t and r = the cost of capital Project Example: The cost of capital for the project is 10%. Financed by Supported by Year Cash Flow 0 $-1000 1 500 2 400 3 200 4 200 5 100 Implemented in cooperation with CAPITAL BUDGET The Internal Rate of Return (IRR) is the discount rate at which the NPV of a project equals zero. The IRR decision rule specifies that all independent projects with an IRR greater than the cost of capital should be accepted. where CFt = the cash flow at time t and Example: From the equation, we find IRR= 16.82% Financed by Supported by Project Year Cash Flow 0 $-1000 1 500 2 400 3 200 4 200 5 100 Implemented in cooperation with CAPITAL BUDGETING PROCEDURE The preparation of capital budgeting can be done in the following procedure: 1. Organization of Investment Proposal - The primary step in capital budgeting is conception of a profit making idea. 2. Screening the Proposals- In big organizations, a capital expenditure planning committee is instituted for the purpose of screening the various proposals received. 3. Evaluation of projects - The next step involves evaluating the various proposals in terms of cost of capital, expected returns from alternative investment opportunities, and the assets’ life through different techniques. 4. Establishing priorities - Unprofitable or uneconomic projects are dropped off after the screening of projects has been done. 5. Final approval - The proposals which are finally recommended are passed on to the top management accompanied by the detailed report about the capital expenditure as well as the sources of funds to congregate them. 6. Evaluation - As a final step, an evaluation of the program, after being implemented completely, is carried out to assess the profitability. Financed by Supported by Implemented in cooperation with KEY STEPS IN DRAWING UP A BUDGET Make time for budgeting Use last year's figures - but only as a guide - Collect historical information on sales and costs if they are available - these could give you a good indication of likely sales and costs. But it's also essential to consider what your sales plans are, how your sales resources will be used and any changes in the competitive environment. Create realistic budgets - Use historical information, your business plan and any changes in operations or priorities to budget for overheads and other fixed costs. Make sure your budgets contain enough information for you to easily monitor the key drivers of your business such as sales, costs and working capital. Accounting software can help you manage your accounts. Involve the right people - It's best to ask staff with financial responsibilities to provide you with estimates of figures for your budget Financed by Supported by Implemented in cooperation with REVIEW YOUR BUDGET REGULARLY Two main areas to consider: Your actual income - each month compare your actual income with your sales budget, by: analyzing the reasons for any shortfall - for example lower sales volumes, flat markets, underperforming products considering the reasons for a particularly high turnover - for example whether your targets were too low comparing the timing of your income with your projections and checking that they fit Your actual expenditure - regularly review your actual expenditure against your budget. This will help you to predict future costs with better reliability. You should: look at how your fixed costs differed from your budget check that your variable costs were in line with your budget - normally variable costs adjust in line with your sales volume analyze any reasons for changes in the relationship between costs and turnover analyze any differences in the timing of your expenditure, for example by checking suppliers' payment terms Financed by Supported by Implemented in cooperation with CONTROL RATIOS To compare actual performance with the budgeted performance Activity Ratio: a measure of the level of activity attained over a period of time. Activity Ratio = Standard hours for actual production Budgeted hours x 100 Capacity Ratio = indicates whether and to what extent budgeted hours of activity are actually utilized. Capacity Ratio = Actual hours worked x 100 Budgeted hours Efficiency Ratio = indicates the degree of efficiency attained in production. Efficiency Ratio = Financed by Standard hours for actual production Actual hours worked Supported by x 100 Implemented in cooperation with