Immanuel Kant (1724

advertisement

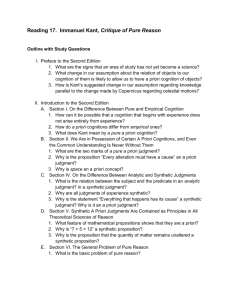

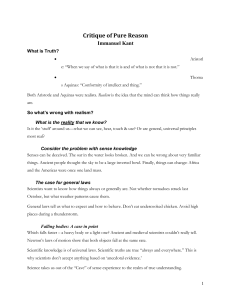

11/27/06 Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) The Critique of Pure Reason (1781, 1787) (Text, pp. 341-363) 1 Anthem 2 Topics covered in the reading 1 The nature, scope, & limits of human knowledge a priori & a posteriori knowledge analytic & synthetic judgments synthetic a priori judgments & how they are possible phenomena, noumena, & the "transcendental ideas of pure reason" 2 The transcendental ideas of pure reason: self, cosmos, & God 3 Morality & metaphysics: freedom, immortality, & God 3 Introductory Note What is knowledge? Answer: Knowledge is verified ("justified") true belief. To know is to believe; the belief must be true (rather than false); and the belief must be verified ("justified"), i.e., proved true. 4 The Rationalist-Empiricist Dispute According to Kant, all knowledge begins with sense experience, but not all knowledge arises out of sense experience. 5 There are two basic types of human knowledge: a posteriori knowledge, which arises from & depends on sense experience; and a priori knowledge, which arises from the operations of the mind & is independent of sense experience 6 The distinguishing characteristics of pure a priori knowledge: Necessity and Strict universality (no possibility of an exception) 7 A priori judgments are necessarily & universally true (or false), whereas a posteriori (empirical) judgments are never necessarily or universally true (or false).* *They are contingently true (or false). 8 A further Kantian distinction Analytic Judgments vs. Synthetic Judgments 9 It's all about subjects & predicates 10 In an analytic judgment or proposition, the predicate makes explicit (explicates) meanings that are already implicit in the subject (e.g., "a triangle is three-sided"). 11 In a synthetic judgment or proposition, the predicate adds to our knowledge of the subject in a way that logical analysis, by itself, cannot (e.g., "some houses are white"). The predicate of a synthetic proposition augments & amplifies our knowledge of the subject. 12 The relationships between analytic, synthetic, a priori, & a posteriori judgments 13 Analytic judgments express a priori knowledge, i.e., they are necessarily & universally true (or false), & they can be verified or falsified independently of sense experience, i.e., by logical analysis alone. (There is no need to test them a posteriori.) 14 "Material objects are extended in space." This proposition is both analytic & a priori. 15 A posteriori judgments (which must be verified or falsified on the basis of sense experience, not through logical analysis) are always synthetic (e.g., "material objects have weight"). 16 So . . . . 17 there are (uncontroversially) analytic a priori judgments, synthetic a posteriori judgments, and analytic a posteriori judgments (which are a waste of time, since analytic judgments can be verified or falsified by logical analysis alone). In addition to these, Kant claims . . . . 18 that there are synthetic a priori judgments (This is controversial!) 19 A synthetic a priori judgment is one that is necessarily & universally true (& thus not derived from sense experience, i.e., it is a priori) and in which the predicate adds something to our knowledge of the subject that could not be known merely by logical analysis of the subject. 20 Examples of synthetic a priori judgments (according to Kant) "Everything that happens has a cause." "7 + 5 = 12" "A straight line is the shortest distance between two points [in space]." "In all changes of the material world, the quantity of matter remains unchanged." "In all communication of motion, action and reaction must always be equal." "The world must have a beginning." 21 This leads to what Kant calls "the general problem of pure reason" 22 23 To this general question, Kant adds several subsidiary questions: "How is pure mathematical science possible?" "How is pure natural science [physics] possible?" "How is metaphysics as a natural disposition possible?" "How is metaphysics as a science possible?" (We will not at this time pursue answers to these questions.) 24 Kant's solution of How are synthetic a priori judgments possible? 25 Kant's "Copernican Revolution in Philosophy" ? Objects Mind 26 According to Kant, the mind does not conform to its objects. On the contrary, the objects of consciousness conform to the structure & operations of the mind itself. 27 The structure of the mind Pure Reason (Vernunft) Understanding (Verstand) Categories Categories of the Understanding Sensibility (Sinnlichkeit) Forms of space & time Forms of Sensibility 28 Kant's overall view Transcendental Ideas & Moral Postulates (Rational Belief) Noumena Reason (Vernunft) Understanding (Verstand) Categories Mind Sensibility (Sinnlichkeit) Objects of Consciousness Phenomena Forms of space & time (Knowledge) 29 Categories of the Understanding 1 Of Quantity Unity (Singularity) Plurality (Particularity) Totality (Universality) 3 Of Relation Substance-Attribute Cause-&-Effect Community (Interaction) 2 Of Quality Affirmation Negation Limitation 4 Of Modality Possibility-Impossibility Existence-Nonexistence Necessity-Contingency 30 The categories of the understanding are applicable only to phenomena that appear to us under the forms of sensibility (space & time); they have no legitimate application to noumena, i.e., realities or alleged realities that transcend the realm of space & time. 31 However, in an effort to construct a totally unified, coherent, & systematic worldview, human reason (Vernunft) thinks beyond the phenomenal realm and formulates ideas of realities (i.e., possible realities) that transcend the world of experience. 32 This takes us 33 from knowledge to rational belief The transcendental metaphysics of Pure Reason 34 The Transcendental Ideas of Pure Reason Self, Cosmos, & God 35 The content of the transcendental ideas 36 The Transcendental Idea of the Self a thinking substance (soul) simple & unchangeable has a personal identity that persists through time exists in relation to other real things outside it experiencer & thinker 37 The Transcendental Idea of the Cosmos (or world-in-general) a unified and infinitely long series of events the totality of all causal series 38 The Transcendental Idea of God The primordial, single, selfsubsistent, allsufficient, supreme ground of being Supreme creative & purposive reason as the cause of the universe 39 The Justification of the Transcendental Ideas They are the foundations for reason's construction & account of the systematic unity of experience. 40 The Idea of the Self enables reason to construe all of "my" subjective experiences as existing in a single subject (my "self"), all of "my" powers of perception & thought as derived from a single source (my "self"), all changes within "me" as belonging to the states of one & the same permanent being (my "self"), and all phenomena in space as entirely different from the activity of thought (i.e., as other than my "self"). 41 In other words, the idea of the Self provides me with a metaphysical foundation for the unity of my experience. 42 The Idea of the Cosmos enables reason to think of the world as if it were a unified collection or totality of infinitely long causal series that can be endlessly investigated by science. In other words, the idea of the cosmos-as-awhole is a stimulus to scientific inquiry. 43 The Idea of God enables reason to see nature as a system grounded in reason and pervaded with purpose since God is Supreme Reason aiming at the ultimate good of all things. 44 In other words, the idea that God (a supremely rational & purposive being) is the cause (creator) of the universe enables us to see the world as a teleological unity in which everything (absolutely everything) serves some purpose. 45 Kant seems to be saying that, unless we assume the existence of the Self (transcendental ego), the Cosmosas-a-whole, & God, the world & our experience of the world will lack systematic unity & coherence. In other words, the world & our experience of the world cannot be completely intelligible (or meaningful) without the transcendental ideas of pure reason. 46 However . . . , 47 the transcendental ideas are "regulative," not "constitutive." That is, they guide or "regulate" our study of the world by leading us to proceed AS IF the Self, the Cosmos-as-a-whole, & God are real. However, the objects of the transcendental ideas (Self, Cosmos, & God) do not "constitute" actual objects of experience; they are "merely" ideal objects, which, if real, add systematic unity & coherence to our experience of the phenomenal world. 48 But we cannot KNOW whether or not the Self, the Cosmos, & God are real because they are "transcendental" (noumenal) objects, i.e., they are not phenomena that appear in space & time & to which the categories of the understanding can be applied. 49 Morality, Happiness, & Metaphysics Freedom, Immortality, & God (The Postulates of Practical Reason) 50 Kant's distinction between theoretical reason (reasoning about the universe, the world of nature) and practical reason (reasoning about human existence & action) 51 As we have seen, pure reason (i.e., pure theoretical reason), in seeking to understand the universe as a whole, formulates certain "transcendental ideas" (of Self, Cosmos, & God). Similarly . . . , 52 pure practical reason, in an effort to see human existence & human moral effort as meaningful, postulates the reality of moral freedom, the immortality of the soul, & the existence of God. (In the Critique of Practical Reason (1788), Kant calls freedom, immortality, & God "the postulates of practical reason.") 53 Freedom of the Will According to Kant, morality (the moral law) tells us what we OUGHT to do. Thus, morality presupposes freedom of the will because, logically speaking, "ought" implies "can." 54 The existence & nature of the moral law In the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant assumes the existence of pure a priori moral laws that determine what we ought and ought not do. In his later works on ethical theory (see footnote on p. 358 in text), he seeks to deduce the moral law from the concept of moral duty (or obligation). 55 According to Kant, reason discerns a relationship between morality & happiness. What is the nature of that relationship? 56 On this subject, there is a difference between the pragmatic law & the moral law. The pragmatic law answers the question, "What must I do in order to become happy?" The moral law answers the question, "What must I do in order to deserve (be worthy of) happiness?" 57 Moral laws are categorical imperatives, i.e., absolute & unconditional moral commands (e.g., "Be honest"); hypothetical imperatives (e.g., "If you wish to have a good reputation, be honest"). they are NOT 58 In general, the moral law says, "Do that through which you become worthy of happiness." 59 Reason is not satisfied with morality all by itself, nor with happiness all by itself. In a completely good world, "a system in which happiness is tied and proportioned to morality [which makes one worthy of happiness] would be necessary." 60 "What . . . is the supreme good of the moral world that a pure but practical reason commands us to occupy?" "It is happiness in exact proportion to the moral worth of the rational beings who populate that world." 61 For such an ideal world to exist, two things are necessary: the existence of God; and the immortality of the soul. Only God can guarantee the ideal proportionality of morality & happiness. If happiness & unhappiness are to be necessary consequences of our conduct in the empirical world, then there must be a future world in which the soul lives on. 62 That’s all, folks! 63