Department of Philosophy

advertisement

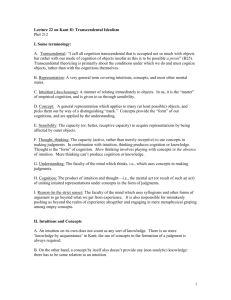

Department of Philosophy Seminar in Eighteenth-Century Philosophy/561A-2009 The Transcendental Deduction in Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason Alison Laywine: Leacock 918, 398-6058, a.laywine@mcgill.ca The focus of this seminar will be a crucial argument in the Critique of Pure Reason – the so-called “Transcendental Deduction”. The backdrop to this argument is Kant’s claim that we have two distinct faculties: sensibility and understanding. Sensibility is the faculty of being affected by objects under the conditions of space and time: we are affected by objects when they act on our senses; and, when they do so we have direct representations or ‘intuitions’ of them. But understanding is the faculty of thinking. We can, in principle, think, even if nothing acts on our senses. Thinking, as such, does not involve intuitions, but it always involves the use of concepts. Concepts are not direct, immediate representations of individual things, but rather representations that convey to us what we take to be interesting about classes or groups of things. We use these concepts to form judgements. If you encounter a friendly dog who knocks you off your feet with canine greetings, you will have a host of intuitions of that dog, which might include impressions of boisterous tail-wagging, celebratory barking, and warm sticky tongue lolling – all of which will be deliverances of sensibility. But the thought that ‘Dogs are undignified’, is a judgement formed in part by a concept that you take to capture whatever it is that identifies the apparition now assailing you – and others like it – as a dog, and not a cat. Kant claims furthermore that all use of concepts in judgements depends ultimately on the use of twelve special concepts of the understanding. He calls these concepts ‘pure’ to indicate that they cannot be derived in any way from experience – unlike the concept ‘Dog’, which you will have formed at least in part by past experience with dogs. These special concepts are the object of the ‘Transcendental Deduction’. For they seem to present us with a problem we do not encounter with concepts like that of Dog or Cat. It seems straightforwardly obvious that concepts derived from experience relate to objects, if for no other reason than it seems that we can successfully communicate with each other when we use them. You know what I mean when I say that dogs are undignified, even if you happen to disagree with me. But the special concepts at issue in the Transcendental Deduction are not derived from experience. They include concepts like that of cause and effect. One may well wonder whether anything we encounter in experience answers to this concept, because nothing prevents us from imagining that the world, as it appears to us anyway, exhibits no causal relations whatsoever. If we can wonder whether the concept of cause and effect applies to possible objects of experience, with all the more reason we can wonder whether it applies to anythng supersensible, i.e., to anything beyond the realm of experience. Such doubts make it seem all the more likely that the pure concepts of the understanding are – to use Kant’s expression – without any ‘sense and meaning’. The task of the Transcendental Deduction is to put these doubts to rest. It succeeds, according to Kant, insofar as it shows that the pure concepts of the understanding relate a priori only to possible objects of experience. (This has as an implication that when we try to apply the pure concepts of the understanding to the objects of metaphysics, as traditionally conceived, the result will be empty talk.) Our task this term will be to study this argument and evaluate it critically. Kant thoroughly revised it for the second edition of the Critique (1787). We will concentrate on this version of the argument, but we will take note of the version that appeared in the first edition (1781) when that can help shed light on things. I am not presupposing that students in the seminar have already read through the first Critique before. But I am presupposing a willingness to undertake a patient, careful, critical, independent reading of the parts of the Critique that are relevant for the seminar. If you do not already own a copy of the book, copies of the Guyer and Wood translation (Cambridge University Press) are available for purchase at the Word Bookstore on Milton Street.