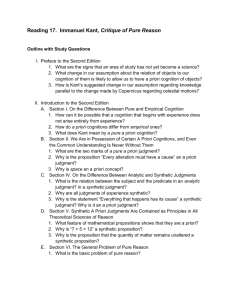

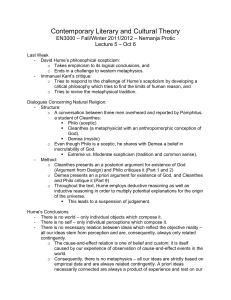

Critique of Pure Reason

Critique of Pure Reason

Immanuel Kant

What is Truth?

e: “When we say of what is that it is and of what is not that it is not.”

Aristotl

Thoma s Aquinas: “Conformity of intellect and thing.”

Both Aristotle and Aquinas were realists. Realism is the idea that the mind can think how things really are.

So what’s wrong with realism?

What is the reality that we know?

Is it the ‘stuff’ around us—what we can see, hear, touch & use? Or are general, universal principles most real?

Consider the problem with sense knowledge

Senses can be deceived. The oar in the water looks broken. And we can be wrong about very familiar things. Ancient people thought the sky to be a large inverted bowl. Finally, things can change: Africa and the Americas were once one land mass.

The case for general laws

Scientists want to know how things always or generally are. Not whether tornadoes struck last

October, but what weather patterns cause them.

General laws tell us what to expect and how to behave. Don’t eat undercooked chicken. Avoid high places during a thunderstorm.

Falling bodies: A case in point

Which falls faster – a heavy body or a light one? Ancient and medieval scientists couldn’t really tell.

Newton’s laws of motion show that both objects fall at the same rate.

Scientific knowledge is of universal laws. Scientific truths are true “always and everywhere.” This is why scientists don’t accept anything based on ‘anecdotal evidence.’

Science takes us out of the “Cave” of sense experience to the realm of true understanding.

1

Problems with universal, ideal knowledge

First, it has to make contact with particular sensible things.

Meteorology has to be about real storms. So it can’t be ‘pure’ thought, like mathematics.

This means that sense experience can somehow disprove universal laws.

The ancients believed that the sun was made of a kind of perfect, eternal matter. Galileo’s discovery of sunspots disproved this.

What exactly are these laws?

For Plato they are eternal ideas in a realm beyond sensation. Newton’s laws were expressed in mathematics.

And what makes them so inviolable?

Hume: There is nothing contradictory about the sun’s not rising tomorrow. What ‘sheriff’ enforces scientific laws?

In short, is knowledge about anything real?

Answers so far

Plato: True knowledge is of eternal Forms or Ideas.

Descartes: Senses are deceptive. Only “clear and distinct ideas” are trustworthy.

Hume: There is no necessity to any matter of fact. Our knowledge is based on sense experience and custom.

Emmanuel Kant

He admired Hume’s analysis, but also Newton’s scientific laws. He said that Hume “awakened [him] from his dogmatic slumbers.”

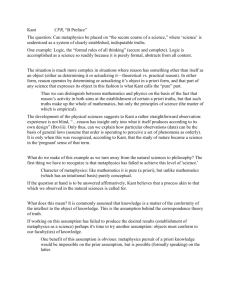

“It has hitherto been assumed that our cognition must conform to the objects.” (realism) But: “Before objects are given to me, that is, a prior, I must presuppose in myself laws of understanding which are expressed in conceptions a priori.”

Kant’s “Copernican Revolution”

Philosophers had always assumed that all our knowledge comes from things ‘out there’. But:

“If the intuition must conform to the nature of the objects, I do not see how we can know anything of them a priori.”

2

That is, we cannot apply scientific laws to new objects. Kant’s solution: Sensation comes from things, but the mind has its own conceptions. Necessary laws come from reason itself.

“Before objects are giving to me, that is, a priori, I must presuppose in myself laws of understanding which are expressed in conceptions a priori.”

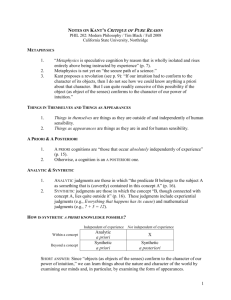

Pure vs. Empirical Knowledge

Kant makes an important distinction.

“But though all our knowledge begins with experience, it by no means follows that all knowledge arises from experience.”

A priori knowledge is absolutely independent of all experience. An important example is the proposition, “Every change has a cause.” (Recall the importance of this to Hume.)

A priori cognitions

The human mind needs some pure a priori cognitions, if it is to know anything. Some general ideas do come from experience. But others are a priori. We know from experience that all bodies are heavy. But this is not strictly universal (think, maybe, of helium balloons.)

“When, on the contrary, strict universality characterizes a judgment, it necessarily indicates… a faculty of a priori cognition. Necessity and strict universality, therefore, are infallible tests for distinguishing pure from empirical knowledge…”

The proposition “Every change must have a cause” is such a strictly universal proposition. And Kant rejects Hume’s analysis, because Hume denies the certainty necessary for science.

Concepts can also enjoy this kind of universality.

Analytic & Synthetic Judgments

Analytic: Predicate B belongs to predicate A.

“Unmarried” belongs to “bachelor”

Every body is extended.

Synthetic: Predicate A does not necessarily belong B.

“Green” does not necessarily belong to “surface”.

A ball doesn’t have to be perfectly round.

3

Judgments of experience are always synthetic.

Synthetic judgments a priori

Kant’s big question: “How are synthetic judgments a priori possible?” How is it possible to know a matter of fact prior to all experience? For instance, we think we know that every event has a cause, or that every quality (such as redness or hardness) has to be found in some substance.

1.

Mathematical judgments are always synthetic, e.g. 7+5=12.

2.

“The science of natural philosophy [physics] contains in itself synthetic a priori judgments, as principles.” Here Kant cites two of Newton’s laws.

3.

Metaphysics must contain synthetic a priori propositions, e.g. “The world must have a beginning.” (N.B. Kant denies that we can actually know anything of metaphysics.)

The Universal Problem of Pure Reason

“How are synthetic a priori judgments possible?”

Therefore we ask how are pure (and not applied) math and science possible? He questions seriously whether metaphysics is possible as a science.

Kant’s final answer

Synthetic a priori judgments are required by reason, not by things. So we can’t know things in themselves. All we know are appearances. Thus, in a way, Kant rejects realism.

What can we know?

Kant believes we can know

Mathematics

The sciences

Morality

But not metaphysics, that is, not about God, the soul, or the world as a whole.

4