Project Management Document

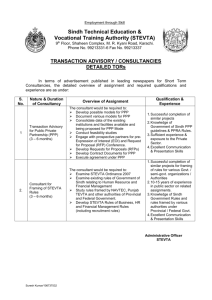

advertisement