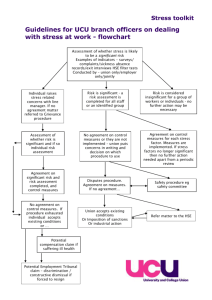

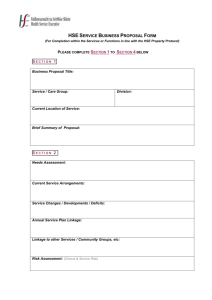

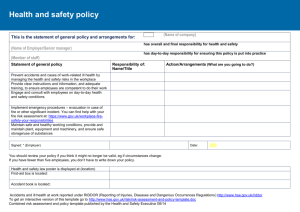

consultative document

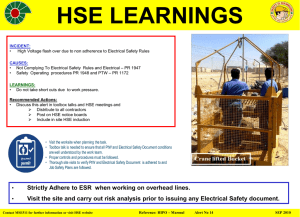

advertisement