Hand Out - Why We Have Feelings about Debits and Credits

[Type text]

NAEP Tier II Professional Academy Burr Millsap

Why We Have Feelings about Debits and Credits

Many of us have incorrect feelings and/or notions about the words Debit and Credit. Let’s find out why.

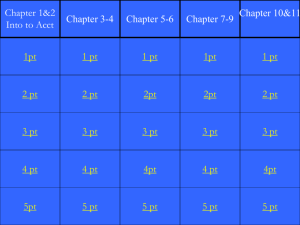

We have seen from above that Debit and Credit are directional words, and that their effects on the balances of the different types of accounts are as shown in the table below.

Account Debit Credit

Type Dr Cr

Assets

Liabilities

Contributed Capital

Retained Earnings

++

- -

- -

- -

- -

++

++

++

Revenues

Expenses

- -

++

++

- -

Now, we know that Cash is an asset and if we set an account up for it we call it an asset account.

And we know from the above table that a Debit entry to an asset account increases its balance.

And yet, too many of us find it impossible to believe that a Debit entry can ever add to the balance of our Cash account. So, one of two things must be false. Either a Debit entry to the

Cash account truly does NOT add to its balance; or the belief that many of us hold is wrong. Of course, the truth is that the belief that many of us hold is wrong.

Let’s see how we got ourselves to this miserable state…and, by the way, it really isn’t our fault that we’re in it. We’re going to look at two examples of how we’ve been led to believe the Debit is

“bad” and Credit is “good.”

In the first example, let’s assume that we’re going to go to our favorite department store and buy some jeans. Let’s assume that the retail price of the jeans is $35.00. Further, let’s assume that instead of paying cash for the jeans, we’re going to get an account with the store and pay next month. To record this transaction on its books, the store will make the following journal entry:

Debit Credit

Accounts receivable

Sales

$35

$35

(to record a sale to customer Green on account)

Looking at our table above, we can see that when the store posts the two lines of this entry it will increase the balance of the Accounts Receivable account, and increase the balance of the Sales account.

Now, we need to understand that the Accounts Receivable (A/R) accoun t is a “control” account.

That is, it is made up of the individual A/R accounts representing each customer. So, let’s suppose that our department store has three customers who have accounts and owe it money at the time we make our purchase:

Smith ......................................................... $100

Brown ............................................................ 45

Jones ............................................................ 70

Total ....................................................... $215

We would represent the fourth A/R to the store and its total A/R balance after our purchase would be $250 ($215 + $35). The main point of this illustration is to show that the account statement we will receive from the store at the end of the month comes from its A/R control account. And when we receive our statement, our purchase will show up under which column, the Debit or the

[Type text]

NAEP Tier II Professional Academy Burr Millsap

Credit? Of course, the answer is it will show up under the Debit column because that is the entry that i s reflected on the store’s books.

So, how did we feel when we read our statement and saw our purchase entry under the Debit column? We felt bad because the entry reinforced what we already knew: that we owed money to the store. And when we owe, we typically do not feel good about it. Therefore, our reading of the word Debit and our feelings associated with it trigger negative impressions of it.

Next month, when we pay off the balance in our account, the store will record the following journal entry:

Debit Credit

Cash $35

Accounts receivable $35

(to record customer Green’s payment on account)

Looking at our table again, we can see that when the store posts the two lines of this entry it will increase the balance of the Cash account, and decrease the balance of the A/R account.

Once again, our account statement will come from the store’s A/R control account. When we receive our statement, our payment will show up under which column, the Debit or the Credit?

And the answer is it will show up under the Credit column because that is the entry that is reflected on the store’s books.

So, how did we feel when we read our statement and saw our payment entry under the Credit column? We felt good because the entry reinforced what we already knew: that we did not owe the store any more. And when we do not owe, we typically feel good about it. Therefore, our reading of the word Credit and our feelings associated with it trigger positive impressions of it.

We must realize that our feelings about Debit and Credit are triggered by information reported to us and about us from the records of people who are NOT us! We can clearly see that the store’s journal entries comply with our Debit and Credit table above, and we can clearly see that when the store debited its asset accounts of A/R and Cash, it increased those account balances. So, we must start to work on our own feelings about Debit and Credit and understand that it is the feelings that are wrong, not the rules.

OK. Let’s take another example. In our first example, we represented an A/R to the department store. What if we represented something on the other side of the Balance Sheet such as an

Account Payable? Would we still wind up with our same incorrect feelings about Debit and

Credit? The answer is yes, and he re’s why.

When you deposit your paycheck with your bank, you become an Account Payable (A/P) to it. In the banking business you are a special type of A/P known as a Demand Deposit Account, or

DDA. Your bank will make the following journal entry when you deposit your check:

Debit Credit

Cash $1,000

Accounts payable - DDA

(to record Green’s deposit on account)

$1,000

When your bank posts the two lines of this entry to its books, it will increase the balance of its

Cash account and increase the balance of the DDA it has set up for you. This is accurate because your deposit increases the amount of cash that the bank has available to it to lend. In fact, that is the essence of banking: to take in money and pay a low interest rate and then lend that money out and charge a higher interest rate. The Credit to your DDA account merely reflects your claim on that cash.

[Type text]

NAEP Tier II Professional Academy Burr Millsap

Now, as with the department store example, the bank’s A/P DDA account is a “control” account. It is made up of the individual DDA accounts of each depositor. So, let’s suppose that our bank has three depositors:

Gray ....................................................... $2,050

Black ........................................................... 550

Smith ........................................................ 1,100

Total .................................................... $3,700

We would represent the fourth DDA to the bank and its total A/P balance after our deposit would be $4,700 ($3,700 + $1,000). The main point of this illustration is to show that the account statement we will receive from the bank at the end of the month comes from its A/P control account. And when we receive our statement, our deposit will show up under which column, the

Debit or the Credit? Of course, the answer is it will show up under the Credit column because that is the entry that is reflected on the ba nk’s books.

So, how did we feel when we read our statement and saw our deposit entry under the Credit column? We felt good because the entry reinforced what we already knew: that we had money on deposit with the bank. . . or more accurately, that we had a claim on the cash on hand at the bank. So, in that type of situation, we typically feel good about it. Therefore, our reading of the word Credit and our feelings associated with it trigger positive impressions of it.

Next month, when we write a check to the grocery store and the bank honors it, the bank will record the following journal entry:

Debit Credit

Accounts payable - DDA $125

Cash $125

(to record honoring Green’s check for groceries)

When the bank posts the two lines of this entry it will decrease the balance of the A/P DDA account, and decrease the balance of the Cash account. The entry reflects that the bank has transferred cash to the grocery store and a decrease in your claim on the cash still remaining in the bank.

Once again, our acc ount statement will come from the bank’s A/P control account. When we receive our statement, our check will show up under which column, the Debit or the Credit? And the answer is it will show up under the Debit column because that is the entry that is reflected on the bank’s books.

So, how did we feel when we read our statement and saw our check entry under the Debit column? We felt bad because the entry reinforced what we already knew: that we have less of a claim on the cash at the bank. Notice that we di d not say, “because there is less cash in our account,” because that is not the most accurate way to state the situation. The bank’s DDA in our name is NOT cash; it is our claim against the cash that is under the bank’s custody and control. In any case, the Debit entry triggers in us a bad feeling.

So one more time, we must realize that our feelings about Debit and Credit are triggered by information reported to us and about us from the records of people who are NOT us! We can clearly see that the bank’s journal entries comply with our Debit and Credit table.

The previous two examples demonstrate to us very clearly how and why we have been tricked into having irrational feelings about the words Debit and Credit. It is not really our fault because we have not had enough experience with Debits and Credits as we would use them in reference to ourselves. Instead, our only knowledge of them is when we see them on other people’s records about us. For that very reason, we must trust our Debit and Credit table, even memorize it, and then understand that it our feelings that are wrong, not the Debit/Credit rules.