Vernon Smith: An Experimental Study of Competitive Market Behavior

advertisement

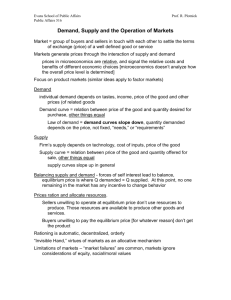

Vernon Smith: An Experimental Study of Competitive Market Behavior Economics 328 Spring 2005 How to Win a Nobel Prize in 3 Easy Steps . . . Some papers are important as much for what they started as for what they are. Smith’s 1962 paper on markets is an archetypical example of this. It wasn’t the first paper ever written in experimental economics. Thurstone had written an influential experimental paper on indifference curves in 1933 and Chamberlin, Smith’s advisor, wrote an important experimental paper on markets in 1948. However, these papers were largely isolated events. After Smith’s work, experimental economics became an ongoing line of research within economics. “Columbus is viewed as the discoverer of America, even though every school child knows that the Americas were inhabited when he arrived, and that he was not even the first to have made a round trip, having been preceded by Vikings and perhaps others. What is important about Columbus’ discovery of America is not that it was the first, but that it was the last. After Columbus, America was never lost again.” – Al Roth Christopher Columbus Research Question Smith’s experiments were designed to study the neo-classical theory of competitive markets. This is the simple model of supply and demand curves that every economics student learns in the first few lecture of principles. In spite of the importance of the competitive model to economics, there was little direct evidence prior to Smith’s work that the theory actually would work. • Field data is too dynamic to see if equilibrium is being achieved. • Chamberlin’s (1948) earlier work using a decentralized market mechanism found that generally the prices were too low and the volumes too high as compared to competitive equilibrium predictions. • Smith’s experiments were designed to give the theory its best chance to work – this reflects a desire to establish if there were any cases were the market would equilibrate as predicted by the theory. Smith was interested in studying what configurations of supply and demand were most (or least) likely to lead to equilibrium, and was also interested in the dynamics that led to equilibrium Experimental Design and Procedures Sessions were run in classrooms for hypothetical payoffs. • The results were later replicated using monetary payoffs. • In one session the subjects were graduate students in a class on economic theory. • In evaluating Smith’s work, it is important to remember that he was first. Subjects were divided into two groups, buyers and sellers. • To induce demand and supply curves, each buyer was given a card with his/her maximum willingness to pay and each seller was given a card with his/her minimum reservation price. • Each subject was allowed to buy/sell one unit of the good per trading period. • Trading takes place through a double oral auction. Unlike Chamberlin’s earlier work, this is a highly centralized market. Buyers and sellers are aware of all bid, asks, and transaction prices. Summary of Sessions The sessions focus primarily on the effect of vary the shape of the supply and demand curves. Some attention is also paid to the effect of changing market institutions and making traders more experienced.. • Test 1: Basic supply and demand • Tests 2 and 3: Varies steepness of supply and demand curves without changing equilibrium price. This allows Smith to study the process that leads to equilibrium. • Test 4: Flat supply curve. This leaves no surplus for the sellers. It is interesting to think of this in light of much later experiments on equity in market games. • Test 5: Studies the effect of an increase in demand. Given that subjects don’t know how demand has changed, you might expect this to disrupt convergence. • Test 6: Equilibrium gives a very large surplus to the sellers by using a supply curve that goes vertical. Once again, this is interesting in light of the later experiments on market games. • Test 7: Very steep supply curve relative to the demand curve. • Test 8: Buyers were not allowed to make bids in early periods. This was supposed to simulate retail markets. The question is whether this prevents convergence to equilibrium. • Test 9 and 10: Each individual is allowed to make two transactions, doubling the amount of experience received. This is expected to speed convergence. Initial Hypotheses Markets are expected to converge to the competitive equilibrium. • According to the “Walrasian” hypothesis, this convergence should be faster when there is larger excess demand (or supply). So, for example, convergence should be faster in Test 2 than in Test 3. • The “excess rent” hypothesis focuses on unrealizable profits at a price – the higher these are, the faster prices should adjust. [Historically, this has not been an important hypothesis.] • Allowing more experience should speed up convergence, while changing market institutions should slow convergence. Results – Convergence to Equilibrium The double oral auctions tend to converge strongly towards equilibrium and achieve high levels of efficiency. For example, the results for Test 1 are shown top right. This is true even when either demand or supply shifts over time. See Test 5 results, bottom right. This is a very basic result, but is the most important result in the paper. Competitive market equilibrium is a central concept in economic theory, but generally can’t be observed in the field. These results prove that competitive equilibrium can work (but not that it must work). Results – Uneven Splits of Surplus Test 4 and Test 7 both feature uneven (predicted) splits of the total surplus between buyers and sellers. These sessions are among the worst in terms of convergence to equilibrium. • Test 4 prices were consistently above equilibrium, giving some surplus to the sellers. • Test 7, which isn’t quite as extreme as Test 4, only converges very slowly to equilibrium. Prices are consistently too low (compared to competitive equilibrium) giving some surplus to buyers. These results can be viewed as a precursor to the sorts of results on fairness that we have studied extensively. Results – Speed of Convergence Comparing Tests 2 and 3, the supply and demand curves are flatter in Test 2 than in Test 3. This means that a small change in prices from the equilibrium leads to larger excess demand (amount demanded – amount supplied) in Test 2 then in Test 3. If the speed of adjustment is related to the size of excess demand, we should see faster adjustment in Test 2. This is exactly what is observed in the data. Smith finds more support for the excess rent hypothesis than for the Walrasian hypothesis. This result is largely of historical interest – the convergence results above are the important results. Results – Inceasing Subjects’ Experience Tests 9A and 10 replicate Test 7, but allow traders to use their values/costs twice in each period. • By doubling subjects’ experience, the speed of convergence will be increased. • This appears to be true, especially if you look at Test 10. This probably isn’t the right way to test this hypothesis though – what you really want is subjects who have already been in one market experiment to participate in a second experiment with different demand and supply curves. Conclusions While Smith draws many conclusions from the data, the most important conclusion is the most basic one: “The most striking general characteristic of tests 1 – 3 5 – 7 9, and 10 is the remarkably strong tendency for exchange prices to approach the predicted equilibrium for each of these markets.” It must be remembered that Smith designed his experiments to give the theory its best chance. These experiments don’t establish that in general the theory of competitive equilibrium will have much predictive power. On a more general level, this paper played an important role in illustrating how controlled laboratory experiments let economists understand phenomena and theories that were hard to observe in the field. In the field, one never knows what the underlying supply and demand curves are, so you can never truly know that the competitive equilibrium has been achieved. In the lab, you can directly observe the emergence of equilibrium. Further Research on Markets Smith’s general results on convergence have been replicated many times. DOA markets are remarkably good at converging to equilibrium under a wide variety of circumstances. This remains true even if supply and demand curves are shifting (although random shifts do worsen convergence). Convergence can be quite sensitive to market institutions. Seemingly small changes in the rules for queuing can substantially affect the speed of convergence. Larger changes in the institutions such as using a posted price market can greatly slow convergence, even leading to non-convergence in some cases. Market power has mixed effects on convergence to equilibrium. Holt, Langan, and Villamil (1986) find prices that are significantly above equilibrium when sellers have market power, but others have found little effect in DOA markets. More generally, the impact of market power is going to depend on the game being played. When a single individual can easily manipulate market prices or when institutions reduce competition among sellers, departures from equilibrium are more likely. Game theory does a fairly good job of predicting when departures from equilibrium are likely, although it does a poor job of predicting the size of these departures. Nobel Prize Winners of the Future?