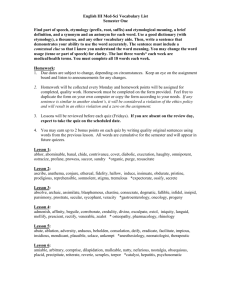

For the main part of your paper, include at least two

advertisement

CONNECTIONS IN EARLY LITERATURE: BRITISH LITERATURE BEFORE 1700 English 366 Dr Graham N Drake Fall 2014 MW 7-8.20PM; additional activities (see schedule) Welles 216 Office: Welles 217A, ext. 5266; office hours: M 9.15-9.45PM; TR 10-10.30AM; W 4-6PM; virtual office hour on phone and occasionally in the office (see below): F 9.30-10.30AM; email: drake@geneseo.edu and GrahamD960@aol.com; evening messages: office number; weekends: West Hartford, Connecticut (860) 231-9488 OBJECTIVES “English” literature starts with Caedmon. The earliest English poet was supposedly an illiterate cowherd taught by an angel to compose verse. From there literature in England continued through what historians call the Old English (or Anglo-Saxon) and Middle English periods and headed into the Early Modern Period (a/k/a the Renaissance). Our course stops about there, sometime in the mid-seventeenth century. But what is British literature? We could start with geography. British literature comes from the British Isles, which consist principally of two large islands: Great Britain (home of three countries: England, Scotland, and Wales) and Ireland. Some of this literature appears in Welsh, Scots Gaelic or Irish; some in standard London English; some in regional dialects; some in Latin or even a form of French known as Anglo-Norman. “British” is even more of a political word than a geographical one: it refers to the governmental, economic, and cultural structures emanating from London. Sometimes “British” is a synonym for “English” or even “London”; sometimes it’s decidedly nonEnglish indeed. Since this survey course will provide a foundation for further literary study, we will emphasize genre, tradition, history (of literature and its cultural context), and technical literary terms. We will look closely at earlier forms of the English language and its dialects by attempting prose translations of selections from our textbooks in class. We will also read poetry (and sometimes prose or drama) out loud during every class (sometimes more than once); everyone will recite a poetic or dramatic selection; and the final exam will be a presentation about the recitation. This course requires the amount of reading, writing, and participation appropriate for a challenging 300-level course, requiring you to reach just a little beyond what you have accomplished before. You get what you put into it; the more you read and study and ponder British Literature from different viewpoints, the more you will come to understand it in ways you might never have imagined. LEARNING OUTCOMES FOR ENGL 300-LEVEL COURSES: Students successfully completing this ENGL300-level course will develop an ability to read texts in relation to history. understanding of how texts are related to social and cultural categories (e.g., race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, class, ability), enterprises (e.g. philosophy, science, politics), and institutions (e.g., of religion, of education). understanding of how language as a system and linguistic change over time inform literature as aesthetic object, expressive medium, and social document. OUTCOMES Students successfully completing Connections in Early Literature: British Literature Before 1700 will accomplish the following: describe the history of British literature from its beginnings to the Restoration in specific detail understand political, social, and cultural contexts of British literature in this period apply a knowledge of basic poetic and literary terminology to modes, genres and sub-genres (such as epic, lyric, ballad, sonnet, or drama) work closely with the literal meanings of texts in earlier forms of the language gain additional experience in written research skills and in oral presentation. TEXTS (in order of reading) Abrams et al. The Norton Anthology of English Literature, Ninth Edition, Volume I. Tales of the Elders of Ireland. (Oxford) You may purchase these books through the College Bookstore, through Sundance Books, or online. Note: if ordering online, please make sure that you have precise, up-to-date editions of each text. REQUIREMENTS One five-page essay on a British literature topic (provided by instructor): 10% of semester grade Midterm exam: 15% of semester grade Six quizzes (15 minutes per quiz): 25% of semester grade (lowest grade will be dropped; thus, each remaining quiz will be worth 5% of the semester grade) RECITATION PROJECT (30% of semester grade) Breakdown of Recitation Project grade: o Recitation of memorized poem: 10 % of semester grade (completion is pre-requisite for giving final presentation and writing five-page accompanying paper) o Five-minute final presentation: 10% of semester grade o Five-page accompanying research paper: 10% of semester grade Class participation (including general preparedness, reading aloud, large group discussion, small group discussions and in-class tasks): 10% of semester grade On-line postings: postings to class wiki during certain specified periods (see class schedule): 10% of semester grade We will discuss the nature and format of these requirements as we proceed. AN A B C OF INFORMATION a's A semester grade of A is kind of like the Holy Grail: it's hard to achieve, but a few hardy members of the Round Table do find it. Such a grade means not merely goodness but excellence in every aspect of this course, especially in the quality of your writing (logic, development, use of evidence, persuasiveness, insight, audience appropriateness, organization, style, clarity, conciseness, diction, grammar, punctuation and spelling) and the enthusiasm of your class participation (brilliance, eloquence, judgment, graciousness, wit, evidence that you have been reading on schedule and possibly being trilingual). all i ever needed to know i learned in kindergarten In an age dominated by the discourse of the Fox News Channel, I worry that America is becoming a desert for courtesy. We don't treat each other as worthy of dignity when we discuss ideas and controversial topics; we don't listen. That's why I think we all need to listen to Robert Fulghum. The forgotten lessons of early childhood are the keys to grownup civil discussion. For this class, I think Fulghum would say, "Show up on time, listen politely while others speak, wait your turn, take an active interest, take your nap later, clean up after yourself, leave with a smile." Happy, well-ordered civilizations, British or otherwise, start with these tips. I don’t mind at all if you bring your dinner to class. If food or coffee doesn’t distract you but can keep you focused, then bring it along. (Note: I cannot be bribed with food, but it usually puts me in a happy mood.) A SPECIAL PLEA: I have to admit that I find it incredibly distracting when people leave during the middle of a discussion or lecture for a restroom break or other reason. Please do whatever you can to take care of personal needs before or after class (in my longer classes, during the mid-class break). If you have a real emergency, that’s fine, but otherwise, we all need you here, so do stick around. attendance Notice how much class participation counts for under REQUIREMENTS. Obviously, class attendance makes participation possible at all. Being here helps you get into the rhythm of the course, provides you with the most accurate, up to-date information, and gives you a chance to think, talk, react, and consider. So “getting the notes” from someone doesn’t quite match the experience of really attending class. I expect attendance as the default minimal commitment to this course. I do not see a real reason for casual absences, and I am notoriously unsympathetic to them. (Your future employer will be more than notoriously unsympathetic to casual absences: she will fire you.) On the other hand, I will always accept understandable excuses for absences—an illness or death of a relative or friend, or recognized religious observances (please do not make up your own religion for the occasion). I would prefer that you document such absences with a note from a doctor, parent, minister, etc. I will always accept a videotaped excuse from Anthony Edwards (formerly of ER) or Ben Affleck…or Jake Gyllenhaal. OK, I’ll stop. Note: under College guidelines, faculty are permitted to set an attendance policy for individual courses. In this class, you may take one unexcused absence. Each additional unexcused absence will mean a penalty of 25 points on class participation (for example, from 80% down to 55%. Another scenario: three unexcused absences subtracted from a class participation grade of 70% = -5%). Anyone not using the single unexcused absence will receive a bonus of 25 points on class participation. cell phones In order to reduce sudden distractions, please turn your mobile phone off during class (including vibrate mode). However, I will leave my own phone on for security reasons (in case New York State’s emergency alert system needs to contact us). If it's one of my zany relatives, I’ll roll my eyes and not pick up…. class participation means just that, participating, not just good attendance. Can you imagine saying that you participated in a triathlon just because you showed up and got the T-shirt? Of course not. Same thing goes for class. Much of your education comes from arguing and discussing and seeing if you can offer opinions worth more than marshmallow fluff. In a word, participation equals learning; and your participation teaches your fellow classmates. For suggestions on how to participate, see a's. Also, see speaking. Remember, you are the life of this party. You can also enhance your class participation grade through extra credit and even through doing well on the quizzes (see below). You will receive a midterm grade for class participation to get a sense of where you stand. disability accommodations If you have obtained a disability accommodation, I will be happy to discuss your needs confidentially. Also, if you think you should consider such accommodations, The Office of Disability Services can help. Here is their policy statement: SUNY Geneseo will make reasonable accommodations for persons with documented physical, emotional, or cognitive disabilities. Accommodations will also be made for medical conditions related to pregnancy or parenting. Students should contact Dean Buggie-Hunt in the Office of Disability Services (tbuggieh@geneseo.edu or 585-245-5112) and their faculty to discuss needed accommodations as early as possible in the semester. This statement can also be found, along with other important information about services, etc., at http://disability.geneseo.edu . email I encourage you to stay in touch with me by email. This is a good way to ask questions about procedure—or, I hope even more, to ask questions of intellectual curiosity. (This makes me smile. Do it!) In the spirit of individual empowerment, I may sometimes answer your question with a question—or suggest where you can find the answer on your own. My complete address is drake@geneseo.edu . Since I often use my America on Line address, I strongly suggest that you always send messages to both of my email addresses simultaneously, especially on the weekends. This other address is GrahamD960@aol.com . esl esl stands for “English for Speakers of Other Languages” or “English as a Second Language.” If you speak a language other than English, you may have issues about grammar, vocabulary, style, and composition that people who speak only English do not share. The ESL Lab in Milne can offer advice that goes beyond the expertise of tutors in the writing learning center. You can contact the Lab Supervisor and Coordinator, Irene BelyakovGoodman, at x.5328 or visit her in Erwin 217. essays You will write two essays for this class, each five pages long. First, I will hand out a set of possible paper topics on the day of our library visit. This five-page paper will be due on THURSDAY, 2 OCTOBER BY 11AM IN THE ENGLISH DEPARTMENT OFFICE. Your second paper (6-7 pages) will be due on BY 8PM ON THURSDAY, 11 DECEMBER VIA EMAIL. It will be graded and returned to you electronically. This paper will be based on your memorized poem, which you must recite in order to qualify to write the paper and participate in the final presentations. Here are some general instructions for this paper: Please start with a brief introductory paragraph with essential details about the author and his/her other works (if the author is known), leading to the thesis of your essay. Next, you should briefly summarize the poem’s content and identify any meter or rhyme scheme in a single paragraph; obviously this does not apply to prose, or to some translations of Old English poetry, but in those cases you should indicate this fact. For the main part of your paper, include at least two of the following considerations in some detail (make sure that your thesis reflects this): Allusions (references to earlier literature, mythology, the Bible, history, or ideas; sometimes your textbook will briefly identify an allusion. Your job here would be to move beyond identification by giving the context of the allusion—where does it originally appear, and what does it mean in that source—and how its presence in your passage helps construct its meaning) Argument/logic (i.e., does the passage present an assertion with some kind of proof or evidence, sometimes cast in an “if –then” structure) Characterization Imagery Metaphor/simile Metrical effects (what meter, rhyme or alliteration suggest for the meaning of the poem) Narrative structure Symbol Theme Word play (puns, metonymies, synecdoches, or other rhetorical figures) You should use at least one journal article for the paper as well; this means an article that appears in a scholarly peer-reviewed journal (not in a book of essays). For this requirement, the article must exist in a hard-copy form (even if it also exists online or is only available in a PDF format). But you may also have many more sources; a good rule of thumb for a short paper is to have as many sources as the number of pages. Be sure that you make clear and understandable transitions between paragraphs. Please also consult the geneseo online guide, especially the section entitled "Conventions on Writing Papers in the Humanities" and the writing guidelines. If you need advice about your essay, come see me, email me, phone me, or stop by the writing learning center. extra credit You may earn extra credit by memorizing a poem (I will distribute a list of possibilities) from the assigned readings and reciting it in front of the class. (Limit: two recitations per person.) You may also earn extra credit by attending selected all-college lectures and writing a 2-3 page critical review that includes about two-thirds summary and one-third analysis. Depending on the quality of your work, each report or memorization may earn you up to 30 percentage points applied to your class participation grade. Example: Your class participation grade stands at 70%. You write a critical review and recite a poem, one earning 15 points, and one earning 20. Your final class participation grade then stands at 105%, which will thus have additional weight in determining your semester grade. Remember, you can't lose points writing a review, and you'll expand your world besides. Another way to earn extra credit: write a response to one of your classmates’ posts on our myCourses page. The response should constitute one paragraph (at the most, two), and you can earn up to four extra credit points for your response, depending on its quality. final exam See final presentations. final presentations The final exam will actually be a series of presentations, taking place on MONDAY, 15 DECEMBER, BEGINNING AT 7PM. We will begin promptly at 7 PM; any late arrivals will distract your classmates as they try to give their presentations. Your presentation will be graded using a rubric which I will share with the class a few weeks ahead of time. This presentation forms part of the recitation project, along with the memorized poem and your second essay. To be eligible to give your final presentation, you must recite your memorized passage in class. Furthermore, absence from the final presentation will be graded as a zero plus a 50% penalty on class participation. During the final presentation period, you will make a five-minute oral presentation that summarizes the major points of your second paper. You may use notes (and, if you wish, an overhead transparency) to assist you. (Because of logistics in a large class, we will unfortunately not be able to use sophisticated multimedia software such as PowerPoint or even the white boards/blackboards; you may use up to two transparencies, however). Your grade will be based on the clarity and fluent expression of your oral presentation and its content. Our goal is to create a series of mini-presentations that will recap the major highlights of British literature and provide each other with another chronological sequence of British literary history. Note: we will observe timing strictly. Besides making sure that you arrive on time (why not even try to arrive a little early?) you should have practiced your presentation so that it takes no more than five minutes but no less than four. I will give you a 20-second warning towards the end of your presentation, but in order to be fair to your classmates, you will need to finish precisely at the end of your presentation. Also, to make things run smoothly, the person waiting to give the next presentation will take a seat near the front of the classroom at the 20-second warning and be ready to start immediately. Once we have completed final presentations, I will be available in my office for additional consultation until the end of the official final exam period at 10.20PM. g.r.e.a.t. day G.R.E.A.T. Day (Geneseo Recognizing Excellence, Achievement, and Talent) takes place on 21 April 2015. This day combines the former HUPS (Humanities Undergraduate Paper Symposium), the Undergraduate Research Symposium in the sciences and social sciences, and other creative and scholarly activities. No classes will meet on this day, but high-quality papers from our own class may be eligible for a G.R.E.A.T. Day session. In these student-run sessions, students whose papers have been accepted will read them aloud and engage in discussion with other session members and audience members. This experience is just like a regular academic conference where your professors deliver papers or chair sessions. Only the best papers are selected for G.R.E.A.T. Day, so it's quite an honor. If I write “G.R.E.A.T. DAY—see me” on your paper, it means I'd like to have you apply to read it at G.R.E.A.T. Day 2015. Even if your paper is not accepted, nomination alone indicates that you've written a pretty terrific essay, and you should still include this on a résumé or a graduate school application. home This section should be called my multilocational personal life. During the middle of the week, I'm in the Geneseo area. On other days (generally Thursday night through Monday morning) you can find me at home in West Hartford, Connecticut. Please check the proper phone numbers at the beginning of this syllabus, and feel free about telephoning me wherever I am. hovering If you are hovering between two possible semester grades, say, between an A- and a B+ — then I will assess your work on the whole to figure out which of the two grades to award. It's important for me to assess not only your numerical average but also how you've improved—and especially how you've contributed with your class participation. i still don't understand iambic pentameter So let's talk. Come see me during my office hours, schedule an extra appointment, see me after class, phone me, or email me. If you don't think you're “getting” a text or a concept, let's discuss it to see if we can come to a way to see things more clearly; I can also steer you towards books that give background information beyond the material you can find in the Norton. laptops Laptops have become part of the regular culture of Geneseo. They are terrific for taking and organizing notes, following along on a website in class, making a PowerPoint presentation, or looking up information that might be part of a specific class activity. Yet part of using laptops effectively means using them with courtesy; there is such a thing as "laptop etiquette." It is impolite to disengage yourself from class by surfing the web, instantmessaging, or looking at materials inappropriate for public places. These activities may distract your classmates and make it more difficult for them to attend to what they are trying to understand, learn, and contribute to. Improper use of your laptop is also self-defeating; you’re somewhere else; you miss being engaged in the present moment; you’re missing from the rest of us. So, if you want to surf, do it later. The Web is always available to you, but the time we spend here in class is more fleeting, and it will not come again. late papers Papers are due on scheduled dates at the beginning of class unless otherwise indicated. Generally I grade late papers down—2/3 of a letter grade for every day or portion of a day that the paper is late (e.g., from Adown to B). In rare circumstances, I will accept late papers or give extensions, but your reason has to be good— death and religion are two categories I can think of off the top of my head. memorized poem and recitation project During class on 3 September, we will hold a poem lottery. (A few people may have a prose passage or a dramatic monologue to recite.) You will need to memorize the poem you draw by 29 October; starting on that day, we will have several recitations per class meeting for the rest of the semester, and you will be writing your second essay on the poem as well. Memorizing a poem means more than getting the words right. Indeed, this is not an exercise in mere rote presentation. Let your poem sink in; spend time with it; discover its emotions and nuances. EMBODY ITS WORDS. Your recitation will count for 10% of your grade, so you will want to give it all the expression and vocal beauty that the poem deserves. Give yourself time to prepare as well by scheduling your work evenly over the weeks before your recitation; it does not help to cram at the last minute. Also, please ready yourself to recite on your scheduled date. The recitations are organized in chronological order to reinforce the linear history of British literature, a fundamental concept of this course. We also need to spread recitations across the semester so that we use class time efficiently. Thus, the only exceptions for rescheduling involve serious illness, family emergency, a religious observance, or a similar grave concern that you should discuss with me as soon as possible. Please note: you will need to recite the memorized poem in class in order to qualify to write the second essay and the final presentation. This series of three linked assignments constitutes a complete recitation project. You will soon receive a set of guidelines for an effective recitation and, later on, a grading rubric. In addition, a theater student will visit our class twice this semester for two in-class workshops. midterm exam The midterm exam for Fall 2014 only will be a take-home exam. The exam will require answering three out of four mini-essay topics in two paragraphs each. The questions will ask you to analyze the use of theme, symbols, poetic conventions, historical backgrounds, or other related literary analysis on readings and videos that we have encountered so far, including at least one question involving Tales of the Elders of Ireland. Make sure to review your primary readings, the introductory and background material in Norton, and all class lecture notes and handouts from the beginning of the semester through 8 October.. Questions for this exam will appear on email beginning the Friday before Fall Break; you must turn in the exam between 7 and 8.40PM via email, which I will monitor during that time. Paste your entire exam into the body of your message—no attachments, please. my courses On our myCourses page, I will post handouts for class and, eventually, the study questions. Please print out the handouts or download them to a laptop that you will be using for the semester. At any given time, I will ask you to refer to these handouts in class. office hours Note my office hours above. If those times are not very good, we can try to schedule an appointment. Since I'm not in Geneseo until the evening on Monday, and sometimes not at all on Fridays, I encourage you to talk to me on the telephone if you like. (See telephoning). On Fridays that I'm here, my on-campus schedule varies, but I will usually be in the office from 10-11AM. On Fridays that I'm not here, I'll be available at the Connecticut phone number from 9.30-10.30AM. (Check my email update for the current week's details.) If I'm going to be somewhere else, I'll let you know. I don't mind at all if you call me when I'm off campus—in fact, I encourage you to do so. peeves Mine, that is, not necessarily in order of importance, include: not using staples; confusing its and it's (read your writing guidelines thoroughly); the extremely common and, to me, utterly baffling misspelling of “definitely” as “definately” (we should require Latin from kindergarten to grad school so that people will know that “definitely” derives from the verb “finio, finire, fini, finitum,” “to finish”); writing “based off of” when the more logical term is “based on”; sitting silent as a frozen mushroom—ever tried to strike up a conversation with one?—and not jumping to answer a general discussion question (show you know lots more than a frozen mushroom, and see speaking); making me see the class as a refrigerator car full of frozen mushrooms; concluding essays with “In conclusion...”; using the phrase “today's society” (an entryway into anachronistic vagaries); trying to define something by using Webster's or any other dictionary, as if the dictionary were the last word on defining rich, complex concepts that you are smart enough to explicate on your own; using those giant-format blue books; forgetting to bring blue books to an exam; walking in late (see all i ever needed to know i learned in kindergarten; but walk in late rather than not walking in at all); having Jake Gyllenhaal up to your dorm lounge for Cheez Whiz and Doritos without inviting me. plagiarism When you use someone else's words or ideas without acknowledging your debt, you commit plagiarism. So please give credit to other people's words. Furthermore, if you are writing on the same topic as a friend, do not consult about the paper beforehand; you may find yourself guilty of a type of plagiarism (I'm serious; I've already seen students do this during my career). A plagiarism conviction can mean a zero on your paper. For more complete information, consult the current college catalogue under “Academic Dishonesty.” printer quality I actually don't care if your papers have a few typos or pen-and-ink corrections as long as everything is nice, dark, and legible. If you can possibly swing it, please use a letter-quality or laser printer—or even a good typewriter. postings to mycourses For each class that is not listed as “EXT” (see the schedule below), you must spend twenty minutes posting material to our myCourses page (where you will find a posting section under “Course Materials.” During the class period before a non-EXT class, I will announce a posting assignment that you will need to complete; you will need to spend a minimum of twenty minutes working on the posting, and you will also need to actually upload your post during one of three designated times: at the end of the final 20 minutes of the class period (i.e., between 8.20 and 8.40PM; to do this, I would suggest remaining in the classroom). at the end of the twenty-minute period following the official class period (i.e., between 8.40 and 9PM). on the following Friday morning during any twenty-minute period before 12 noon (for this posting, please document the twenty-minute period you chose at the end of your posting). Include your name at the end of the text you post as well. Postings may include a question I ask in class; a request to find an article on a particular subject on MLA, examine the text, and state the thesis; a chance to read a short literary excerpt from our Norton or other primary texts and answer a question connected with it; or, occasionally, an “open subject” (your choice of a response to any primary text not listed as one of our required readings; for example, Beowulf; Sir Gawain and the Green Knight; the selection from Margaret Cavendish’s The Blazing World; etc.) Note: you may receive a posting assignment that is slightly different from that of your classmates. To make proper use of your twenty minutes, spend about 12-15 minutes considering the question and the material, then spend 5-8 minutes writing a single, well-constructed paragraph that answers the assignment thoughtfully. This will constitute your post. You should give your post a title, and you should end the text of your post with your name (first and last—not just “Courtney” or “John.”). You can earn extra credit points by writing responses to any post. quizzes At six points during the semester you will have fifteen minutes for a quiz. The quiz will consist of four out of seven brief identification questions. The quizzes will not be cumulative but will cover all readings and discussions from the day of the previous quiz up through the readings for the actual day of the quiz. To do your best on the quizzes, keep up with your readings, think about the readings, study historical background and literary terms, pay attention to and learn specific details, and follow the study questions, and attend class, take notes, and participate. Please be sure to include as much essential information as possible within TWO SENTENCES ONLY. These quizzes will thus give you training in vital skills of abstraction (i.e., boiling down information to its most important elements—not just generic generalities but the most central and specific information) that you will need as part of communication in many professions, even ones that do not directly deal with British literature. Everyone must substitute one take-home quiz for an in-class quiz for any quiz except #1 and #6, which must be completed in class. Moreover, anyone may opt for up to two additional take-home quizzes (again, any except #1 and #6). Even if you are doing a take-home, please come to class at the same time as the regularly scheduled quiz. Please write “take-home option” on your paper. I will then send this take-home quiz the following day via the class email list; it will be based on study questions for the same days covered in the regular quiz and will be due exactly one week later at the beginning of class. Note: if you are diligent enough to receive at least 70% on all six of your quizzes, you will receive 20% of the points on the lowest quiz grade as extra credit points applied to your class participation grade. For example, suppose your lowest quiz score is 80%. 20% of this score is 16%. This will mean 16 extra percentage points on your class participation grade for the semester. Also, if you do not opt for any of the non-required take-home quizzes, regardless of any of your quiz grades, you will receive 10 extra credit points added to your class participation grade. reading In recent studies, most American university students report spending less than half the minimum recommended amount of time studying for classes. The recommended rule of thumb is a minimum of 2-3 hours for each semester hour of classes on one’s schedule. For example, a person taking fifteen semester hours should plan on 30-45 hours per week of reading, re-reading, note-taking, studying, review, and research—depending on the difficulty of the course and your own learning style. You may need to devote even more time when papers are due or exams are coming up. As part of your study plan, please keep up with reading assignments. Class discussion (not to mention your class participation grade) depends on such diligence. This is also the only way you can succeed on the quizzes. You are responsible for reading and having a basic familiarity with the material, regardless of whether we discuss all of it in class. Keep this in mind as you prepare for quizzes and for the midterm. For texts that we do not actually discuss in class, I may assign test questions that a first-time reader of those texts can reasonably answer. You may find this kind of reading takes more time than what you've been used to (especially Middle English texts). Some suggestions: don't wait until the night before class to finish reading. Start a week before if you can; make good use of the weekend; parcel out your reading evenly over a period of days to make it more manageable. Try to find places mentioned in the text on maps in your book. Don’t forget to read and study the material in the introductions, and look for ways that the primary literary texts connect with these introductions. Try to put the text into the context of historical and literary trends you read about in the introductions. Use the index. Look up any word you don't know in the dictionary. Keep a running list of archaic words that are new to you and review these from time to time. Think about what the main "message" of a sonnet or stanza or act of a play is about. Draw diagrams of the text's story or argument. Look for answers to the study questions; keep a running list of questions you would ask if the author were there right in front of you; keep notes in a notebook or in the margin of your text; talk to your roommate about dactylic tetrameter and the sonnet cycle over month-old peanut butter crackers from the snack machine at 2AM. Consider making your goal that of the main character in Rebecca Lee's short story, “The Banks of the Vistula”: Almost miraculously I had crossed that invisible line beyond which people turn into actual readers, when they start to hear the voice of the writer as clearly as in a conversation. Can you do this in an age of televised soundbytes, of super-short magazine articles and worm-brain attention spans? Can you take the challenge to listen to the voice of another age, another people, another way of looking at the world—one that might not even seem relevant to you? Can you move beyond your own circumstances, your own use of language, your own expectations of life, humanity, and the universe? I bet you can. No one else will do this for you; only you can do it. And I bet you can. slashed grades You may sometimes receive an “in-between” grade (e.g., B-/C+); this indicates that your paper was mostly of C+ quality but contains some extra merit that I wish to recognize. Obviously, you will not receive a slashed semester grade; see hovering. snailmail address If you need to mail anything to my home, please send it to 56 Ironwood Road, West Hartford, CT 06117. speaking You may have the easiest time in the world chatting with friends, your aunt, the supermarket stock clerk, your boyfriend's hamster, etc. Speaking in class can be more difficult. You know you're on the spot; there's an electrifying silence from your classmates as they all take in what you have to say, as they process and evaluate your remarks, and as I do the same. Yes, there's a lot at stake when you speak up; but it's very important. First of all, your arguments and opinions are very valuable; so don't let just a few actors command the stage, as happens in many classes. Second, the momentum of this class thrives on variety. If I were to stand up front and read you a semester's worth of notes, without asking you to respond or question or challenge what our texts give us, I might as well just videotape a bunch of lectures and go off to Red Jacket for an endless series of mediocre pizzas. All our voices provide the dialogue/multilogue that keeps us all eager and alive. Third, learning to speak up is as important a skill as writing—and in a world where written communication competes fiercely with oral, you need to practice both. Both skills will aid you as a student, an employee, a citizen, a group member, and a friend. Don't be afraid to say something stupid. If you got into Geneseo in the first place, you already have enough skills to avoid embarrassment. But it happens sometimes. If it does, pick yourself up and move on with dignity. Accept criticism as helpful guidance. Don't worry about losing face with me—I'd much rather that you try to articulate thoughts out loud than remain frozen all through the class, and I won't penalize you if you say something flawed. (If you hardly ever say anything, don't expect to get much more than a D for class participation.) Be humorous and cheerful, sarcastic if you must. But don't cultivate flippancy. Think about other people's points of view, and respect the other person as a person even if you have to show that his/her argument is dead wrong. Think about what the texts are really saying, too. Reading your assignments on time and reflecting on the study questions should give you plenty to say. A tip for analyzing a work of literature in class: start by figuring out the literal details. What does the text actually say? What images, events, characters, or abstract concepts appear, and in what sequence? Do this to establish a concrete background before moving on to interpret—to explicate the meaning of a passage. In general, prefer specific, concrete evidence to vague generalities. staples This is really anal-retentive of me, I know, but please use staples, not paper clips, to hold your papers together. study questions I will send study questions on the readings each week, along with some initial instructions about how to use them. Please hold on to these study questions (i.e., download them or keep them on your email, but do not delete them) since you can use these to review material for quizzes (both in-class and take-home) and the midterm. telephoning I believe it's my responsibility to be available whenever I'm off campus. So please feel absolutely free to call me (up to 10PM MTW; till 11PM RFSSu) whenever you have a question or concern, no matter how trivial. On Monday through Wednesday evenings, you can leave a message for me on my voice mail at the office; on other nights and most holidays, you'll find me in Connecticut. trivia and truth I used to say in my syllabi that I wasn’t so much concerned about whether people remembered exactly what year Edward II died or how many times the word “rose” appears in Shakespeare’s sonnets. I still say that, but with this qualification: a crucial part of any academic degree is mastering basic material in the beginning courses to have a working knowledge of major issues and ideas. This knowledge will assist you in more complex upper-level courses in the future. So you’ll need to spend time learning names and dates, narrative events and images, and definitions of literary devices and genres. You’ll also need to spend time reading archaic forms of the English language carefully to make sure that you get the meaning of every line of text; your Norton anthology assists you in this with its side-glosses and footnotes. Immersing yourself in this material will help you to engage in a higher-order activity: using the most specific and concrete evidence that you can to support an argument or to flesh out a reading of a text. In any event, improving your critical skills and interpretive sophistication is just as important in this class. Your ultimate goal should be to read and understand arguments and ideas—and ultimately to find them useful in some way for understanding the world. turnover time Normally, I return a set of papers 7-10 days after their due date. videos At times we'll be seeing videos on culture or art. We'll discuss these briefly or refer to them as we talk about our major texts. Please treat these videos as seriously as, say, your Norton, i.e., as supplementary texts that put our readings in context and that you'll need to know for exams. worldcat and mla You can access these book and article databases through the College Library’s homepage. WorldCat lists tens of millions of items in all subjects; MLA (Modern Language Association) is specialized for literature and language. There are other Arts and Humanities indexes that you may find useful, as well as Internet search engines such as Google or Yahoo. One helpful site specializing in medieval literature is the Labyrinth at www.georgetown.edu/labyrinth/index.html. The reference librarians can help you negotiate these search engines and give you suggestions for general research directions. writing guide and writing guidelines Read this helpful writing advice on the Geneseo website. The direct/ address is http://writingguide.geneseo.edu/. Study these guidelines and put them into practice to help you construct a good paper. In particular, see the page entitled “Conventions on Writing Papers in the Humanities. Since you will be writing a significant amount for this class, you should also read through my set of basic writing guidelines at https://wiki.geneseo.edu:8443/display/writing/English. Please follow these, and please ask me if you have any questions about them. writing learning center The WLC is a peer-tutoring program staffed by English majors. If you're having trouble with narrowing your thesis, organizing your material, or just getting started, go see the tutors on the main floor of Milne Library. The Center is open for appointments on weekdays and on certain weekend hours; you can make an appointment at http://go.geneseo.edu/wlcform . (The WLC will also take walk-in clients if no appointments are expected.) Find out more about the tutors and how they can help you achieve better writing at http://www.geneseo.edu/english/writing_center. CLASS SCHEDULE AND READING ASSIGNMENTS Important Note: Reading assignments [in italics] are indicated on the date by which you should have them read. We will most likely discuss these readings on that day, but occasionally we will allow for a little flexibility in the schedule. All page numbers refer to the Norton unless otherwise noted. The class will meet together MOST weeks on MW, 7-8.20PM. We will use the balance of required time for this class—40 minutes per week—for either a) Extended class meetings for special activities (never exceeding 8.40PM); marked with “EXT” b) Additional time for posting comments and assignments to myCourses (see the section entitled “postings to myCourses”) 25 August EXT: Introduction 27 August EXT: Video on the early history of the English language; memorized poem list presented to class today; Geographical Nomenclature, A31-32(A-pages refer to appendix); British Money, A33-34; The British Baronage, A38-43; The Universe According to Ptolemy, A48; Introduction to the Middle Ages, 3-19; Old and Middle English Prosody, 24-25 l a b o r d a y 3 September EXT: Memorized poem lottery today; Caedmon and Anglo-Saxon poetry; Introduction to Bede and Caedmon, 29-30; Bede selection, including Caedmon’s hymn, 30-32; Introduction to The Dream of the Rood, 32-33; Dream of the Rood, 33-36; Introduction to Beowulf, 36-41; Introduction to Judith, 109-10; Introduction to King Alfred and The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (on myCourses); Introduction to The Wanderer, 117-18; The Wanderer, 118-19; Introduction to The Wife’s Lament, 120-21; The Wife’s Lament, 121-22 8 September EXT: Theater mini-workshop/guest lecturer; Chaucer; Introduction to Geoffrey Chaucer and The Canterbury Tales, 238-43; General Prologue to The Canterbury Tales, 243-63; Introduction to The Knight’s Tale, 263-64; Introduction to The Miller’s Tale, 264; Introduction to The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale, 282 and 301; Introduction to The Pardoner’s Prologue and Tale, 31011; note: give yourself plenty of time to read Chaucer, and carefully review the guide to “Medieval English,” pp. 19-24 Note: The next several weeks have a relatively light reading schedule. As you're working on your paper, don't forget to start reading Tales of the Elders of Ireland now to avoid the rush. You will need to have read ALL of this book by 8 October. 10 September QUIZ #1: all readings, class lectures, videos, and discussions from 27 August through 8 September, plus today’s readings; Chaucer (cont’d); Introduction to The Nun’s Priest’s Tale, 326; The Nun’s Priest’s Tale, 326-40; Close of The Canterbury Tales, 340; Chaucer’s Retraction, 342-43; Introduction to Chaucer’s Lyrics and Occasional Verse, 343; Introduction to John Gower, 346-48; Introduction to Thomas Hoccleve, 359-60 15 September Langland; Introduction to William Langland, 370-73; Prologue to Piers Plowman, 373-76; “Piers Plowman Shows the Way to Saint Truth,” 380-83; “Christ’s Humanity,” 395-96; Langland (again), 397; “The Crucifixion and Harrowing of Hell,” 397-408; Footnote 6, p. 391, on the Tearing of the Pardon; Footnotes 6-8 on the autobiographical element in the C-Text, 392 (all four footnotes on 391-92 are considered part of your primary readings) 17 September Mysticism and the dawn of women’s writing in English; Introduction to The Ancrene Riwle, 13788;”Parable of the Christ-Knight,” (on myCourses); “The Sweetness and Pains of Enclosure,” 138-40 Introduction to Julian of Norwich, 412-13; Selection from A Book of Showings, 414-24; Introduction to Margery Kempe, 424-25 22 September EXT: LIBRARY VISIT (GO TO MILNE 104, BASEMENT LEVEL); TOPICS FOR ESSAY #1 HANDED OUT AT END OF LIBRARYCLASS 24 September EXT: Video: “The York Mystery Cycle”; medieval drama; Introduction to Mystery Plays, 44749; Introduction to the York Play of the Crucifixion, 439; York Play of the Crucifixion, 440-47; Introduction to Wakefield Second Shepherds’ Play, 449; Introduction to Everyman, 507-08 29 September QUIZ #2; all readings, class lectures, and discussions from 10 through 24 September, plus today’s readings; Introduction to Middle Scots literature; Henryson; myCourses readings: “Medieval Scots Poetic Tradition and a Sample of Modern Scots;” “Scotland: The Land and Its History”; Poems by Robert Henryson: “The Twa Mice” and “The Praise of Age”; Introduction/Notes to the Makars (Tasioulas) [read only the notes to Henryson]; also read in Norton: Introduction to Robert Henryson, pp. 500-01; "The Cock and the Fox," pp. 501-07 1 October Middle Scots literature (cont’d.); Dunbar; myCourses readings from Dunbar: "A Ballad of Our Lady (“Hail, sterne superne!); "Lament for the Makars"; "The Headache"; "To the Merchants of Edinburgh"; from Introduction/Notes to the Makars (Tasioulas): read introduction and notes to Dunbar and all materials on Douglas ESSAY #1 DUE BY 11AM ON THURSDAY, 2 OCTOBER IN THE ENGLISH DEPARTMENT OFFICE, WELLES 226 6 October Introduction to Medieval Irish literature; Introduction to Irish Literature, 122-23; Introduction to Cúchulainn’s Boyhood Deeds, 123; Introduction to “Exile of the Sons of Uisliu,” myCourses; Introduction to Early Irish Lyrics, 128; Early Irish Lyrics, 128-29; Tales of the Elders of Ireland (read first 100 pages, plus the introductory material on the pronunciation of Irish personal and place names) 7 October LOOK FOR EMAIL MESSAGE TODAY ON THEMES TO CONCENTRATE ON FOR THE MIDTERM EXAM FROM TALES OF THE ELDERS OF IRELAND 8 October EXT: Medieval Irish Literature (continued); Tales of the Elders of Ireland; NOTE: class attendance and participation are very crucial today; come prepared, and please do not miss this class without a very, very good reason f a l l b r e a k/ 15 October c a n a d i a n t h a n k s g i v i ng MIDTERM EXAM (see above) 20 October EXT: Theater mini-workshop/ guest lecturer; Medieval Lyrics; Introduction to Middle English Incarnation and Crucifixion Lyrics, 408-09; Incarnation and Crucifixion Lyrics, 409-11; Introduction to Middle English Lyrics, 477-78; “Middle English Lyrics,” 477-78 22 October Malory; “Legendary Histories of Britain,” on myCourses; Introduction to Geoffrey of Monmouth, on myCourses; Introduction to Wace, on myCourses; Introduction to Layamon, on myCourses; The Myth of Arthur’s Return, 130; Introduction to Thomas of England, 132-33; Introduction to Romance, 140-42; Introduction to Marie de France, 142-43; Introduction to Sir Orfeo, 169-70; Introduction to Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, 183-85; Introduction to Sir Thomas Malory, 480-82; Le Morte Darthur, 482-500 27 October Wyatt; Surrey; The Sixteenth Century”, 531-55, then 561-63; “ Literary Terminology”, A10-30 (READ CAREFULLY, REVIEW OFTEN); “Religions in England,” A44-47; Introduction to John Skelton, 564-65; Introduction to Sir Thomas More, 569-71; Introduction to Thomas Wyatt, 646-48; “The Long Love That in My Thought Doth Harbor,” 648; “Whoso List to Hunt,” 649; “My Galley,” 651; Introduction to Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, 661-62; “The Soote Season,” 662-63; “Love That Doth Reign,” 663;“Faith in Conflict,” 671-72 29 October QUIZ #3; all readings, class lectures, videos, and discussions from 20 through 27 October, plus today’s readings; Sidney; Introduction to Sir Philip Sidney, 1037-39; Introduction to The Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia, 1039;Introduction to Astrophil and Stella, 1084; read Sonnets 1, 5, 7, 9, 18, 20, 31, 39, 45, 49, 52, 69, 74, 87, 106-08 (Sonnets begin on 1084); Introduction to Defense of Poesy, 1044-45; Selection from Defense of Poesy, middle of 1048-83 3 November Spenser; Introduction to Edmund Spenser and to The Shepeardes Calendar, 766-69; Introduction to The Faerie Queene, 775-77; “A Letter of the Authors,” 777-80; The Faerie Queene, Book I (begins on 781), Cantos 1, 2, and 4; Introduction to Amoretti and Epithalamion, 985; Introduction to Richard Hooker, 695-96 5 November Recitations begin; Marlowe; Queen Elizabeth I; "The Elizabethan Theater," 555-61; "A London Playhouse of Shakespeare's Time," A49; Introduction to Christopher Marlowe, 1106-07; Introduction to Hero and Leander, 1107-08; "The Passionate Shepherd to His Love," 1126; Introduction to Doctor Faustus, 1127; Doctor Faustus, 1128-63; "Women in Power," 721; Introduction to Mary, Queen of Scots, 736-78; Introduction to Elizabeth I, 749-50; "The Doubt of Future Foes," 758; "On Monsieur's Departure," 758-59; "Speech to the Troops at Tilbury," 76263; Introduction to Roger Ascham, 699-70 10 November Recitations; Shakespeare, Daniel; Drayton; Introduction to the English Bible, 673; Examples from Bible translations, , 674-76; Introduction to the Book of Common Prayer, 689;Excerpts from The Book of Common Prayer, 690-92; Introduction to William Shakespeare, 1166-70; Introduction to Sonnets, 1170; Sonnets 1, 18, 20, 29, 30, 73, 130, 147 (beginning on 1171); Introduction to Twelfth Night, 1187-89; Introduction to King Lear, 1251-54; Renaissance Love and Desire, 100005; Samuel Daniel, Sonnets 32-33, 1014-1; Michael Drayton, Sonnet 61, 1016-17 Richard Barnfield, Sonnets 9 and 11, 1022-23///// 12 November QUIZ #4; all readings, class lectures, and discussions from 29 October through 10 November, plus today’s readings; recitations; Ralegh; Lanyer; Introduction to Robert Southwell, 698;”The Burning Babe,” 699; Introduction to Sir Walter Ralegh, 1023-24; "The Nymph's Reply to the Shepherd," 1024-25; (optional: "What Is Our Life?" 1025); Introduction to John Lyly, 1034; Introduction to Mary Herbert, Countess of Pembroke, 1102; Introduction to Thomas Nashe on myCourses; Introduction to Aemelia Lanyer, 1430-31; "Description of Cookham," 1436-40 17 November Recitations; Donne; “The Early Seventeenth Century," 1341-67; Introduction to John Donne, 1370-72; "Song," 1374-75; "The Canonization," 1377-78; "Elegy 19. To His Mistress Going to Bed," 1393-94; Holy Sonnets, 1410-15; "Meditation 17, 1420-21; Introduction to Izaak Walton, 1424-26; "Gender Relations: Conflict and Counsel," 1648-49; "Inquiry and Experience," 1661; Introduction to Sir Francis Bacon, 1662-63; "Of Marriage and Single Life," 1664-65 19 November Recitations; Jonson; Introduction to Ben Jonson, 1441-43; Introduction to the Masque of Blackness, myCourses; Introduction to Volpone, 1443-44; "To Penshurst," 1546-48; "Song: To Celia," 1548-49; Introduction to “The Ode on Cary and Morison," 1551-52; Introduction to John Webster, 1571-72; Introduction to Elizabeth Cary on myCourses; Introduction to “The Tragedy of Mariam, the Fair Queen of Jewry on myCourses; Introduction to Robert Burton, 1689; Introduction to Sir Thomas Browne, 1696-97 24 November QUIZ #5; all readings, class lectures, and discussions from 12 through 19 November, plus today’s readings; recitations; Herbert; Herrick; Introduction to George Herbert, 1705-07; "The Altar," 1707; "Easter and Song," 1708-09; "Easter Wings," 1709; "Prayer," 1711-12; "Denial," 1713-14; "Love (3)," 1725-26;Introduction to Robert Herrick, 1756; "Corinna's Going A-Maying," 1760-62; "To the Virgins to Make Much of Time," 1762; "Upon Julia's Clothes," 1767 a m e r i c a n t h a n k s g i v i n g Please note: Thanksgiving vacation begins Wednesday, 26 November. Please plan to attend class on the 24th. 1 December Recitations; Wroth; Crashaw; Introduction to Lady Mary Wroth, 1560-61; Selection from Pamphilia to Amphilanthus, 1566-71; Introduction to Richard Crashaw, 1740-41; “To the Countess of Denbigh,” engraving on bottom of 1749-51; Introduction to ‘The Flaming Heart,” 1752; “The Flaming Heart,” 1753-55; Introduction to Henry Vaughan, 1726-27; Political Writing, 1842-43 3 December Recitations; Marvell; Traherne; Introduction to Thomas Carew (pronounced “Carey”), 1768-69; Introduction to Sir John Suckling, on myCourses; Introduction to Richard Lovelace (pronounced “Loveless”), myCourses; Introduction to Edmund Waller, myCourses; Introduction to Abraham Cowley (pronounced “Cooley”), on myCourses ; Introduction to Katherine Philips, 1783-84; Introduction to Marvell, 1789-90; “To His Coy Mistress,” 1796-97; “The Mower Against Gardens,” 1800-01; “The Garden,” 1804-06; Footnote One to “Upon Appleton House,” 1811; “Crisis of Authority/Reporting the News,” 1834-35; Writing the Self, 1867-68; Introduction to Thomas Traherne, 1880; “On Leaping Over the Moon,” 1883-84 8 December EXT: QUIZ #6; all readings, class lectures, and discussions from 24 November through 3 December, plus today’s readings; recitations; Milton; Introduction to Dorothy Waugh, 1878-79; Introduction to Margaret Cavendish, 188485; Introduction to The Blazing World, 1891; Introduction to John Milton, 1897-91; “On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity,” 1901-09; “On Shakespeare,” 1909; Footnotes to “L’Allegro,” 1909-13; Footnotes 1 and 2 to “Il Penseroso,” 1913; Introduction to Lycidas, 1917-18; Introduction to Areopagitica, 1929; Introduction to Milton’s Sonnets, 1939; Sonnet: “When I Consider How My Light Is Spent,” 1942; Introduction to Paradise Lost, 1943-45; “The Verse” and “The Argument,” 1945-46; “Paradise Lost, Book 1, lines 1-127, 1946-49 FINAL PAPER DUE VIA EMAIL BY 8PM ON THURSDAY, 11 DECEMBER 2014 FINAL PRESENTATIONS BEGIN ON MONDAY, 15 DECEMBER 2014 AT 7PM On a final note…why learn about all of this? BECAUSE acquiring this knowledge is difficult. Because you will feel triumphant when it no longer confuses you. Because you will enjoy what you can do with it. Because in learning it you may discover new perspectives on life, new ways of thinking. Because its possession will make you more alive than its alternative, which is ignorance. J. M. Banner and H.C. Cannon DO NOT PRINT THIS PAGE: APPENDIX for future Early Literature / British Literature Before 1700 syllabi (does not apply to Fall 2014): midterm exam Half of this exam will consist of identifications (major characters, authors, literary styles, important historical facts or literary movements); half will consist of two medium-answer (two paragraphs) questions about our readings so far. One of these two questions will be based on Tales of the Elders of Ireland; I will send you an email message on 8 October with some specific themes to concentrate on for the exam. You will have a choice of ten identifications; two choices on the first medium-answer question and two choices on the Tales of the Elders of Ireland question. Make sure to review your primary readings, the introductory and background material in Norton, and all class lecture notes and handouts from the beginning of the semester through 9 October.