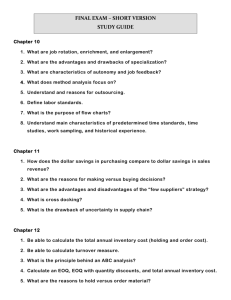

Production Quality

advertisement

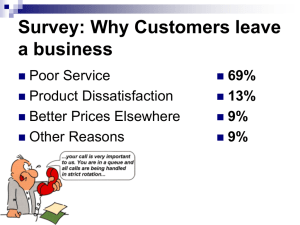

Unit Twelve Production and Quality Management Objectives Get the students to be familiar with the concept of production and quality management. Cultivate the students’ ability of problem-solving. Help the students to grasp the techniques for fast reading. Section A Introduction Production and quality are the most important issues in any business. Efficient and effective production and best quality always increase productivity and thus make the business more profitable. Production is the process of transforming inputs such as raw materials into outputs such as goods and services. As markets have become much more competitive, quality has become widely regarded as a key ingredient for success in business. Pre-reading Before reading the following passage, answer these questions: 1. Do you know about production? 2. What role does quality play in business? Text Production Management Production management refers to the management of a firm’s production activities. Production management is crucial to both manufacturing and service organizations. As an organization grows, it can capitalize on a number of factors that accompany their larger size. Each of these factors is associated with the experience curve, the reduction in per-unit costs that occurs as an organization gains experience producing a product or service. Whenever a company’s output doubles, production costs typically decline by a specific percentage, depending on industry. For instance, with a sales volume of 2 million units, per-unit costs may be $100 in a particular industry. With a doubling of volume to 4 million units, per-unit costs may decline by 15 percent. Another doubling of volume to 8 million units may lower per-unit costs another 15 percent. The experience curve has been observed in a wide range of manufacturing and service industries, including automobiles, personal computers, and airlines. Although the precise percentages are not always known, the principle of the curve can be accurately applied to most production environments. The experience curve is based on the notion that unit costs in most industries decline with experience and is based on three underlying concepts: learning, economies of scale, and capital-labor substitution possibilities. Learning refers to the idea that employees become more efficient when they perform the same task many times. An increase in volume fuels this process, also increasing expertise. This reasoning can be approved in all jobs—line and staff, managerial and non-managerial—at all levels in the organization. Economies of scale—the reductions in perunit costs as volume increases—can be great for business such as automobile manufacturers or Internet service providers. Capital-labor substitution refers to an organization’s ability to substitute labor for capital, or vice versa as volume increases, depending upon which combination minimizes costs and/or maximizes effectiveness. A number of American manufacturers, for example, have shifted their assembly operations across the Mexican border where labor costs are much lower. Firms in other countries have taken similar measures. Recent developments in production technology have modified the traditional capital versus labor dichotomy. A number of facilities have advanced to the point that products are manufactured while no workers are present, often during the night. The role of the workers in such facilities is not to produce the products, but to prepare them for delivery. Seeking to exploit the experience curve can be risky. Increases in volume often involve substantial investments in plant and equipment and a commitment to the prevailing technology. However, as technology changes and renders the plant’s production processes obsolete, outdated capital equipment may have to be discarded. Balancing current investments in plant and equipment with the risk that technology will change, prompting a number of firms to invest in flexible manufacturing systems that can be retooled quickly to respond to market changes. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, popularity increased in the United States and parts of Europe for a concept called business process reengineering—the application technology and creativity in an effort to eliminate unnecessary operations or drastically improve those that are not performing well. As such, companies sought to “eliminate any process that did not add value” to the organization’s goods and services. For example, a number of consumer goods manufacturers during this period began to rethink their packaging operations and many of them eliminated large, cumbersome boxes in favor of less costly shrink-wrapping. Some analysts have noted a reemergence of this trend in the early 2000s. Speed in developing, making, and distributing products and services can be the source of a significant competitive advantage. In fact, an application of speed known as “timebased strategy” is a top priority in many organizations. Companies that can deliver quality products in a timely fashion become problem-solvers for their customers and are more likely to prosper. Motorola, for instance, cut the time it takes to produce a cellular telephone, from fourteen hours to less than two, while retail prices have fallen dramatically. Speed is equally important in customer service. Production Quality In the late 1970s and early 1980s, strategic managers became interested in a concept borrowed from the Japanese known as quality circles, whereby managers and workers would meet to discuss and implement production changes that improved quality and efficiency. This interest evolved in the late 1980s and early 1990s into a heightening of interest in quality broadly known as total quality management (TQM). Developed by W. Edwards Deming, TQM refers to the totality of features and characteristics of a product or service that bear on its ability to satisfy customer needs. Historically, quality has been viewed largely as a controlling activity that takes place at or near the end of the production process, an after-the fact measurement of production success (i.e., the “quality control” department). However, the notion that quality is measured after an output is produced has eroded, and quality is now seen as an essential ingredient of the product or service being provided and a concern of all members of the organization. Hence, from a production standpoint, producing a quality product lowers defects and minimizes rework time, thereby increasing productivity. In addition, making the operative employees responsible for quality eliminates the need for inspection. As an extension of the TQM philosophy, Six Sigma seeks to increase profits by eliminating variability in production, defects and waste that undermine customer loyalty. Six Sigma is a systematic process that utilizes information and sophisticated statistical tools to improve production efficiency and quality. Practitioners receive training and advance to various levels of certification in Six Sigma concepts. A number of companies began adopting the approach in the late 1990s and early 2000s and have reported substantial savings. Even in the best-managed businesses, problems can arise that result in poor product or service quality. Companies must guarantee an acceptable level of quality to install confidence among buyers and avoid loss of business when such problems occur. The concept of the guarantee is both a quality and a marketing concern. Some companies even offer unlimited money-back guarantees. In an effort to minimize short-term costs, however, many companies ignore this competitive advantage. Often, guarantees lapse after a very-short period or time or contain too many exceptional conditions to be effective competitive weapons. Managers must balance the costs associated with a superior guarantee with its benefits and tailor the package to the organization’s strategy. Changes in the competitive environment can even spark quality decisions from competitors within a given industry. For example, following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, many airlines engaged in vigorous cost-cutting to help stop losses that were to follow. Although a number of airlines eliminated meals on domestic flights, Continental actually took steps to improve cabin comfort and retain quality meals on its flights. Hence, while most airlines moved to address critical short-term financial concerns, Continental perceived an opportunity to emphasize quality and seek to develop long-term competitive advantage. Research and Development Another function closely related to production is research and development (R&D). Product/service R&D refers to efforts directed towards improvements or innovations in the quality or uniqueness of a company’s outputs. Process R&D seeks to reduce operational costs and make them more efficient. R&D is most important in rapidly changing industries where production modifications are most often required to remain competitive. Process innovations may need to be technologically sophisticated to be implemented effectively, or they may not even be used at all. For this reason, a number of ideas for process innovations are never fully implemented. Product/service innovations also involve risks. Once introduced, new products or services may not generate a level of demand sufficient to justify the R&D investment. RJR Nabisco, for example, has spent millions of dollars to develop and produce a smokeless cigarette. Although the new brands such as Premier and Eclipse were introduced with considerable fanfare, demand never materialized and the product was canceled after a short time. Interestingly, Japanese companies often abandon their new products as soon as they are introduced in order to force themselves to develop new replacement products immediately. U.S. companies have responded by increasingly forming direct research links with their domestic competitors, asking their suppliers to participate in new-product design programs, and taking ownership positions in small start-up companies that have promising technologies. Purchasing All organizations have a purchasing function. The relationship between purchasing and production is critical. In many respects, the quality of a firm’s outputs cannot readily exceed the quality of its raw materials. In manufacturing firms, the purchasing department procures raw materials and parts so that the production department may process them into finished products. At the retail level, company buyers purchase items from manufacturers for resale to the consumer. Buyers must identify potential suppliers, evaluate them, solicit bids and price quotes, negotiate prices and terms of payment, place orders, manage the order process, inspect incoming shipments, and pay suppliers. It is critical to note that low costs are not the only consideration in purchasing activities. A low price is useless if the item breaks down in the production process or fails to meet customer demands. On the other hand, excessive quality unnecessarily raises costs and prices. Purchasing is the first step in the materials management process. Indeed, purchasing also includes the operation of storage and warehouse facilities and the control of inventory. Consequently, these related tasks can only be efficiently and effectively conducted if they are viewed as parts of a single operation. The just-in-time inventory system (JIT) demonstrates the interrelationships. JIT was popularized by Japanese manufacturers to reduce materials management costs. Using this technique, the purchasing manager asks suppliers to ship parts at the precise time they are needed in production in order to hold inventory, storage, and warehousing costs to a minimum. As such, JIT has reduced costs for a number of large firms. Although American manufacturers have moved in the direction of JIT, this approach works particularly well in Japan where large manufacturers wield considerable bargaining power over their much smaller suppliers. Because it places great delivery demands on suppliers, JIT does not tend to work well when manufacturers do not possess great bargaining power, as is often the case in the United States. In addition, an occasional late supplier can cripple a firm’s production process. A JIT system also makes a company highly vulnerable to labor strike. Recently, for example, one of the plants that supplies parts to GM’s Saturn, which uses the JIT system, suddenly found itself unable to produce any cars because it had no inventory of the more than three hundred metal parts that it purchased exclusively from the supplier whose plant was struck. Many large manufacturers in the United States seek a middle ground between traditional inventory systems and JIT. Most have reduced their number of suppliers from a dozen or more to two or three to control delivery times and quality. Companies are also strengthening their relationships with their suppliers and providing them with detailed knowledge of their requirements and specifications. By working together, buyers and suppliers can improve the quality and lower the costs of the purchased items. Post-reading Answer the questions on the text: 1. Does production management refer to only manufacturing organizations? Why? 2. What does “experience curve” mean? Can you give some examples? 3. What is the role of the workers in a factory with advanced facilities? 4. What does “BPR” mean? 5. How can changes spark quality decisions? 6. Why do Japanese companies often abandon their new products as soon as they are introduced? 7. Why is “JIT” important? 8. Why do many large manufacturers in the United States seek a middle ground between traditional inventory systems and JIT? Section B Reading skills Identifying the Author’s Purpose People write for a purpose: to inform, to persuade, to entertain. Some clues that effective readers can watch for to help them identify what kind of writing they’re dealing with: 1) Informational writing features facts and evidence, not opinions or value judgment; 2) Persuasive writing features emotional appeals: opinions and arguments; rhetorical questions; evaluating language and/or judgmental language Speed Reading Task When you read Section B, scan it for clues that help you identify the author’s purpose. Is the text informational, persuasive or meant mainly to entertain? Or does the author have more than one purpose? True or False 1. __ Total quality management is a business philosophy of organization-wide commitment to continuous improvement, with the focus on teamwork, increasing customer satisfaction, and lowering costs. 2. The objective of TQM programs is to build an organization that only produces products that are considered first-in-class by its customers. 3. “Getting things right first time” means better not produce at all than produce something defective. 4. Quality circle members are free to collect data and take surveys and often focus on personal complaints and problems. 5. Benchmarking is defined as the continuous process of measuring products, services, and practices against the toughest competitors or those companies recognized as industry leaders. 6. Continuous improvement ignores small innovations and changes. KEY: T F T F T F Section C Case Study Task Study the case and discuss the questions in groups. Selling a Bright Idea—Along with the Kilowatts By the time Florida Power & Light (FPL) Co. became the first U.S. company to capture Japan’s prestigious W. E. Deming Prize in 1989, the Miami-based utility had become a kind of mecca for corporate America’s quality mavens. Visitors marveled at FPL’s quality department, numbering 80 staffers. And they were awestruck by the utility’s 1,800 quality-improvement teams. “We had checkers checking checkers in everything we did.” Says J. Thomas Petillo, then an executive in the quality office. In the end, however, FPL kept better tabs on quality than it did on its basic business. The utility’s managers, preoccupied with such quality issues as timely billing and preventing downed power lines, woke up too late to the population explosion in southern Florida and the sudden surge in demand for power. FPL had to buy electricity from nearby utilities. It even had to initiate rolling brownouts to conserve power. The year it won the Deming, FPL’s profits fell 8%, to $412 million, even though its revenues climbed 13% to $5.3 billion. With results like that, many companies would have turned out the lights on quality programs. Not FPL. Instead, the utility revamped its entire quality approach—this time with an emphasis on cost reduction. Nowadays, FPL’s bottom line is much brighter. Its profits rose 23% last year, to $572.4 million. And building on its reputation as a Deming winner, FPL has launched a thriving return-on-quality consulting business. FPL’s Qualtec Quality Services Inc. unit has 52 consultants, annual billings of more than $13 million, and a list of 199 clients worldwide, from US West Inc. to Britain’s Nuclear Electric PLC. Qualtec’s approach is straightforward. First, it tries to persuade managers to throw out their old views of quality. The consultants break up management—from top executives through middle managers—into groups to talk about quality and how it should be used only as a means to produce healthier results. The message is spread through teams made up of managers and blue-collar workers. Then, with everyone in agreement on how to define quality, Qualtec does a top-to-bottom review of the way a company operates, identifying potential quality improvements that could yield financial benefits. At American President Co., a shipping company based in Oakland, Calif., Qualtec consultant Joe L. Webb made three transpacific voyages before singling out 45 processes that were key to keeping American President’s ships running smoothly. Of those, Webb figured that 25, including loading cargo and meeting schedules, were critical to customers—and therefore likely candidates for quality improvements. Since then, Webb hs recommended a number of measures, such as streamlining paperwork to reduce the time it takes customs officials to clear cargo. Not all of Qualtec’s consultants have time for cruises. As more companies look for tangible payoffs from quality, they are also demanding speedier results. “Twelve to 18 months? Surely you can do better than that?” is the common refrain from clients, says Petillo, now Qualtec’s president. In response, Qualtec has formed “turbo teams” of consultants and managers to develop quality programs in a matter of weeks, not months. Gauging the financial impact of quality improvements is still a challenge. To help its clients, Qualtec is developing new computer software to measure the cost of quality against projected financial results, such as sales and return on capital. As for the old Deming process that FPL once championed, Petillo thinks it still has merits. But even the Japanese quality devotees he sees these days are no longer blind to cost. Japan’s weakened economy has seen to that. “Before, the Japanese wouldn’t talk about cost,” says Petillo. “Now they understand.” It’s a revelation that Qualtec is helping to spread. Questions for discussion: 1. What were the positive outcomes of Florida Power & Light’s obsession with total quality management? What were the negative outcomes? 2. The Florida Power & Light case highlights a potential flaw in the TQM philosophy. What is this flaw? 3. Given the information in this case, how do you think the TQM philosophy needs to be modified in order to improve its effectiveness as a management tool? NOTES 1. the experience curve 经验曲线(又称波士顿经验曲线)。1960年,波士顿咨询 公司(Boston Consulting Group)的布鲁斯•亨得森( Bruce D. Henderson)发现生产成本和总累计产量之间 存有一致相关性,首先提出了经验曲线效应( Experience Curve Effect)。它是一种表示生产单位时 间与连续生产单位之间的关系曲线。简而言之,就是如 果一项生产任务被多次反复执行,它的生产成本将会随 之降低。每一次当产量倍增的时候,代价值(包括管理 、营销、分销和制造费用等)将以一个恒定的、可测的 比率下降。 2. Six Sigma 六希格玛管理理论。希格玛是用来衡量流程品质的变 异或分配状况的, 也就是说, 控制流程的产出, 将产出 的变异控制在一定界限之内, "流程每百万次的操作机 会, 只允许出现3~4个失误". 这种理论是许多一流国际 企业如摩托罗拉、德州仪器、花旗银行、福特汽车、 柯达等对抗景气变化、确保市场领先地位的经营新手 法. 3. the just-in-time inventory system (JIT) 一种库存管理的方法,旨在降低库存水准,将需求与供 应达成至当需求产生时供应就能及时到达去满足需求 的库存管理方法。