The Resident Schools - Amazon Web Services

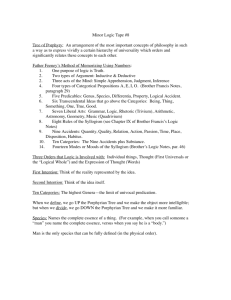

advertisement