Radical Revision PowerPoint Presentation

advertisement

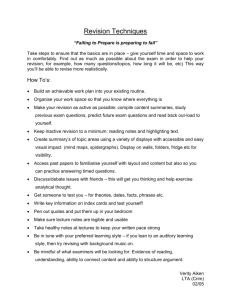

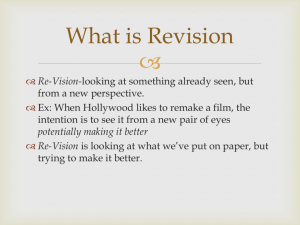

Radical Revision Teaching Revision Techniques Revision: What does it mean to revise? What is your revision process? How has your revision process changed over the past few years? How did you learn about revision? What are your general feelings about revision? What about those of your classmates? Revision: The word revision comes from the word revise, which means “to see again.” Re (again) Vise (to see) How can we teach other writers, and ourselves, to see again? How can we become confident and enthusiastic about the revision process so that we can, in turn, excite others by the process? What do our students consider revision to be? Some students may not meet our expectations for revision because they understand the term very differently than we do. When Nancy Sommers, a researcher at Harvard, asked student writers and professional authors what "revision" meant to them, they gave her wildly divergent answers: "…just using better words and eliminating words that are not needed. I go over and change words around." "…cleaning up the paper and crossing out. It is looking at something and saying, no that has to go, or no, that is not right." "…on one level, finding the argument, and on another level, language changes to make the argument more effective." "…a matter of looking at the kernel of what I have written, the content, and then thinking about it, responding to it, making decisions, and actually restructuring it." Whereas the students described revision as a process of making adjustments at a more superficial level ("just using better words" and "cleaning up"), the professional authors described revision as a process of making fundamental changes to a paper ("finding the argument" and "actually restructuring"). Instructors of Comm-B and WI courses, no doubt, have the latter definitions in mind. But when students and instructors understand the term revision so differently, it is no surprise that students don't undertake the kinds of revisions instructors have in mind. Yet other students may be willing to revise and may comprehend the kinds of revision that their instructors have in mind, but still make only superficial corrections to their drafts because they lack specific strategies to help them successfully undertake more fundamental revisions. How much do students revise? For the novice writer, however, revision appears to be synonymous with editing or proofreading. An NAEP (1977) study found that students' efforts at revision in grades 4, 8, and 11 were devoted to changing spelling, punctuation, and grammar. Students seldom made more global changes, such as starting over, rewriting most of a paper, adding or deleting parts of the paper, or adding or deleting ideas (Applebee, et al., 1986). Resistance to Revision from Acts of Revision Revision is trivial, the nitpicky correcting of superficial niceties. Revision is unnecessary. Revision makes things worse. Revision is wasted time. Revision is drudgery; only the first draft is creative. Revision is a sign of failure, and criticism a personal affront. You don’t have time to revise. You don’t know how to revise. Modeling the Revision Process Show your students examples of revision Particularly your own revisions. Show an essay you wrote and the many versions that you wrote before coming to the final draft. Present the story “A Good, Small Thing” or “The Bath” by Raymond Carver, both of which have two published versions which are each wildly different. If you have time, you might also show clips from the film “Short Cuts” in order to show how the stories were revised by the director and producer of the film and talk about what makes the film version of the story different from the two versions they have read. Revision Exercises Try a descriptive outline. Read your writing out loud. Draft generously and cut down later. Highlight the Center-of-Gravity sentence in each paragraph of your draft. This is similar to but not the same as composing a descriptive outline, which asks that you create a new summarizing sentence for each paragraph. Peter Elbow suggests that the center-of-gravity sentence in freewriting is that sentence which calls attention to itself, seems core, crucial, provocative, evocative, and so on. At the end of each day of drafting a text, write down what you’d do to this draft if you had one more hour, one more day, one more week, and one more month to revise. As you begin the next drafting session, start by reading these notes to help you reenter the draft. More exercises… Instead of a fat draft, which entails a bit of freewriting and sometimes unmindful expansion, expand more mindfully. Add a paragraph (or a stanza) between each paragraph (or stanza) that already exists. If you have only one paragraph, add a new sentence between each old sentence and see what that expanded paragraph tells you to write next. Write a contrasting paragraph to each assertion you made in your draft. Still more… Insert a list into your text and then explore the items in the list. Instead of using the list to compress an idea, use it to open up ideas. Two days after finishing your first full-breath, shareable, draft, copy your conclusion to a new file and write two pages, using this conclusion to begin your new draft. When working with a research paper, resist including any quotes. Now that you’re more learned and expert about your subject, try to detail your points in your own words (you can include and attribute sources later). If you can’t do this, you have a clue that the sources in your full-breath draft may be shoring up a discussion that you don’t really understand. Yes, more… Play transition cop. Highlight your transition. Footnote each with an explanation of how each transition (word, phrase, or even paragraph) functions in the text. Look for predictable patterns and try to alter them in conventional and unconventional ways. Review the highlighting to identify overtransitioned sections and undertransitioned sections. Give your text (physical) voice. Add dialogue to your text, no matter what the genre. Let the addition of quoted, spoken words complicate and open up your text. Grammar B English 101 Grammar B Grammar is essentially a set of conventions that everyone agrees to follow. Grammar A is the set of conventions that produces formal, standard English, the set you’ve been learning and required to reproduce in all your papers for school. Grammar B is another set of rules that only certain professional writers get away with, but which produces meaning much more accurately and expressively for certain occasions. Winston Weathers’ article “Grammars of Style” (in Rhetoric and Composition, Ed. R. Graves, 1984. Porstmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook Heinemann, 1984) is my source for this handout. Below are some ways that you can use Grammar B in the next version of your paper: Crots. A crot is a “chunk” of sentences or text that all goes together in some way. It looks like a “note” without the text that it’s notating. You could write a series of crots as “snapshots” separated by space or asterisks. Labryinthine Sentences. A long, winding, endless sentence which usually follows Grammar A within phrases but not necessarily in the sentences as a whole, which may use parentheses, series set off by semicolons, embedded phrases, explanations within explanations (such as why this particular sentence is not really a very labyrinthine sentence because it is too short and too straightforward.) Sentence Fragments. Use them. Often. To give a sense of uncertainty. Or separation. Lists. Generally A minimum of five Usually Independent of a sentence Possibly Written horizontally or vertically or otherwise Sometimes Looks like a poem Double-Voice: Two or more competing or complementing perspectives can be written in the same text “breath” using parentheses, italics, spacing, questions, or just much different styles. Yeah, right, I’m sure they understand double-voice with that incredibly hopeless sentence. Double-voicing is a dialogue without Grammar A dialogue punctuation and without the framing devices for dialogue. Geez, maybe I should write this in columns as a better example and don’t I need to warn them not to overuse the computer-font/styles? Changing fonts or print styles is not double-voicing, though, so don’t use the computer tricks instead of thinking out your meaning. No, this belongs below with the guidelines. Synchronicity. If the writer scrambles verb tenses and time markers, the reader got the sense that the point will be less about had a point that about becoming a point. Collage/Montage. Crots, lists, fragments, and labyrinthine sentences, poems, descriptions, maxims, schedules, stories can be combined into a collage, a loosely organized group of different kinds of text. Grammar B, continued… Guidelines for Producing a Grammar B draft: Don’t change topics/it’s too late now. If you conceive of a Grammar B-like device that fits what you want to say (that is, breaks one rule of Grammar A to good effect). Do it. Don’t change font styles every other word or add obscure symbols and call it Grammar B. It won’t B. Have fun. Play. Take a Chance. If it Fails because you tried something that didn’t work, it didn’t Fail. If it fails because you didn’t try, it failed. Do as the handout describes, not as it does. This handout uses too many different Grammar B techniques because it’s trying to illustrate possibilities rather than make sense. The POINT of this assignment, which I place at the end of the handout instead of the Grammar A position at the beginning of the handout, is to understand better what Grammar A is all about by using Grammar B, to explore what Grammar A (and Grammar B, perhaps) fails to express, to be politically aware (instead of politically correct) of who gets to make rules like Grammar A and who doesn’t, who gets to use Grammar B and why, what the rules of Grammar A accomplish in terms of communication, expression, meaning-making, to explore further the concept of revision, by writing a radically different version of a paper (or, in your case, a post) and to imagine more possibilities and power in language than Grammar A (or our assumptions and ignorances about Grammar A) allow us. Reading and Sources Bishop, Wendy. (1997). Elements of Alternative Style: Essays on Writing and Revision. Portsmouth: Boynton Cook. Bishop, Wendy. (2004). Acts of Revision: A Guide for Writers. Portsmouth: Boynton Cook. Hoaning, Alice S. (2002).