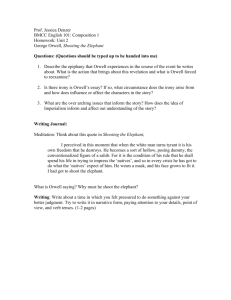

File - English Assist Satire

advertisement