The Ordained Outcome

advertisement

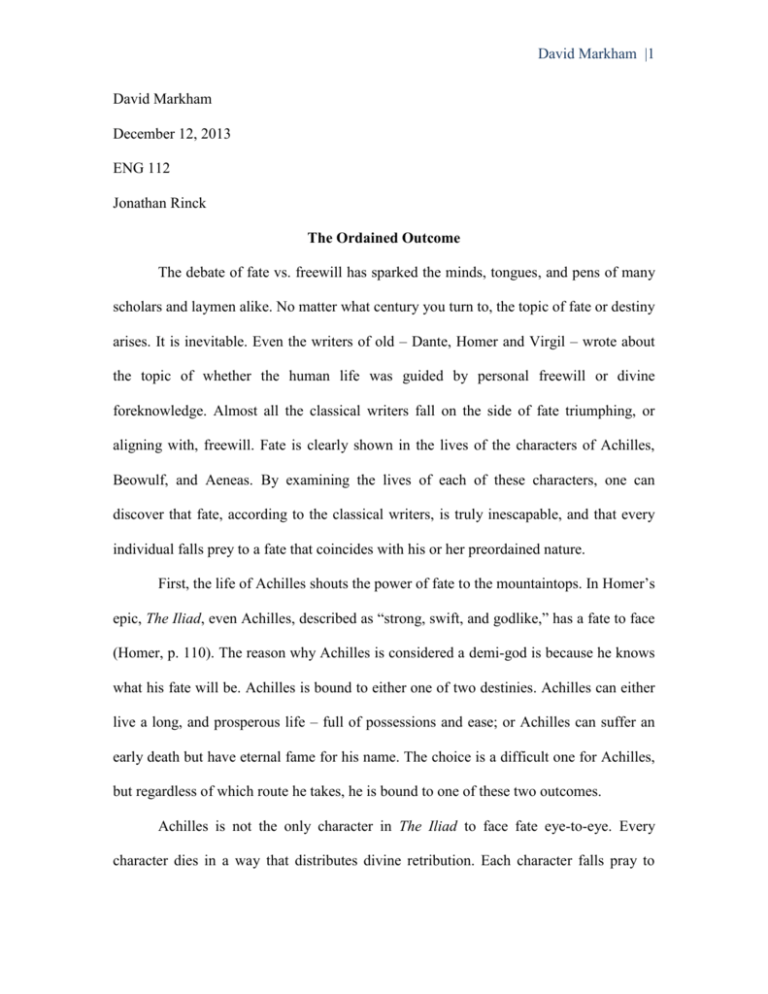

David Markham |1 David Markham December 12, 2013 ENG 112 Jonathan Rinck The Ordained Outcome The debate of fate vs. freewill has sparked the minds, tongues, and pens of many scholars and laymen alike. No matter what century you turn to, the topic of fate or destiny arises. It is inevitable. Even the writers of old – Dante, Homer and Virgil – wrote about the topic of whether the human life was guided by personal freewill or divine foreknowledge. Almost all the classical writers fall on the side of fate triumphing, or aligning with, freewill. Fate is clearly shown in the lives of the characters of Achilles, Beowulf, and Aeneas. By examining the lives of each of these characters, one can discover that fate, according to the classical writers, is truly inescapable, and that every individual falls prey to a fate that coincides with his or her preordained nature. First, the life of Achilles shouts the power of fate to the mountaintops. In Homer’s epic, The Iliad, even Achilles, described as “strong, swift, and godlike,” has a fate to face (Homer, p. 110). The reason why Achilles is considered a demi-god is because he knows what his fate will be. Achilles is bound to either one of two destinies. Achilles can either live a long, and prosperous life – full of possessions and ease; or Achilles can suffer an early death but have eternal fame for his name. The choice is a difficult one for Achilles, but regardless of which route he takes, he is bound to one of these two outcomes. Achilles is not the only character in The Iliad to face fate eye-to-eye. Every character dies in a way that distributes divine retribution. Each character falls pray to David Markham |2 something called hubris. Hubris is a deathly pride which a character develops when he tries to out-do, or escape fate. In the end, although it is not recorded in The Iliad, Achilles falls prey to his own pride and perishes young. He dies from a wound in his heel, ultimately succumbing to fate, not freewill. Not only is fate clearly displayed in the life of Achilles, but also in the life of another classical character form a different side of the world – Beowulf. Not unlike Achilles and the other Greeks and Romans of the past, Beowulf also ascribes to a higher power. When Beowulf first visits the Danish shores to engage the monster, Grendel, he is fully aware that his fate is not his own. Beowulf’s battle cry is thus: “And may the Divine Lord in His wisdom grant the glory of victory to whichever side He sees fit,” (Anonymous p. 1194). Beowulf completely embraces that his fate, and the outcome of this battle is not a result of his own exertion but that of divine decree. Furthermore, after Beowulf defeats Grendel and his mother, he is given a warning by Hrothgar concerning future kingship. Hrothgar tells Beowulf the tale of how terror stuck his kingdom after fifty years of prosperity, just as it will happen to Beowulf fifty years into his kingship. Just as it happened to Hrothgar, darkness falls upon Beowulf’s prospering kingdom after fifty years – but this time it did not take the form of a shunned Grendel or a indignant mother, but instead, the form a dragon. The wyrm that Beowulf must face is not just a giant reptile, but also a wyrd. A wyrd, simply put, is one’s fate. The dragon itself is an embodiment of Beowulf’s demise. Every other enemy that Beowulf has faced and conquered had motive; but this dragon has none. Its intent is malicious. This wyrm embodies everything that Beowulf cannot conquer. Beowulf is a strong, capable warrior, but even he cannot best something of such David Markham |3 magnitude without paying the ultimate price. The dragon is the fate of Beowulf, not just an enemy, because there is nothing Beowulf can do to escape it; it had always been there, dormant, waiting to one day unleash its terror and administer Beowulf’s untimely demise. Finally, fate is clearly shown in the life of Aeneas as recorded in Virgil’s Aeneid. The entire journey of Aeneas from the gates of fallen Troy to the land that would later be called Rome is entirely a tale of fate, and not of choice. The tale of Aeneas really starts when he flees the besieged city of Troy with his family. Aeneas is prompted to flee, not by his own human notions, but rather a divine calling. The ghost of Hector, a fallen hero, visits sleeping Aeneas to warn him that Troy has fallen. “Give up and go, child of the goddess,” Hector prompts. He goes on to say that it is the fate of Aeneas for him to find “great walls that one day you’ll dedicate” (Virgil, p. 960-961). This is Aeneas’ call: to find and found Rome. Throughout the journey of Aeneas, fate is the deciding factor in all his major decisions. For a while, Aeneas stays with a queen by the name of Dido, because both Juno and Venus willed it. After the allotted time was over, Aeneas was prompted to leave, again not by his own will, but the will of the gods. Aneas tells Dido that he would stay “If fate permitted me,” (Virgil, p.984). And he goes on even to say, “I sail for Italy not of my own free will” (Virgil, p. 985). One of the striking differences between Aeneas and other Greek and Roman figures is that he completely accepts his fate and denounces his freewill. At the end of his journey, his fate is accomplished and Rome is founded in the land promised. Through the lives of these characters, one can clearly see how classical writers had a proper grip on whether or not our lives are governed by freewill or fate. Christians David Markham |4 must know and believe that God is sovereign, even if we do not understand it. The writers of old provide a good perspective for how we view our lives. If mythical gods have grand plans, then it should be given that the true God of the Bible has an even more splendid, perfect plan that will come to pass. Works Cited Anonymous. "Beowulf." The Norton Anthology of Western Literature. Ed. Sarah Lawall. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2006. Print. Homer. "Beowulf." The Norton Anthology of Western Literature. Ed. Sarah Lawall. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2006. Print. Virgil. "The Aeneid." The Norton Anthology of Western Literature. Ed. Sarah Lawall. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2006. Print.