Intersectoral Resource Flows in China Revisited--

advertisement

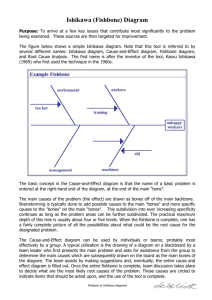

Intersectoral Resource Flows in China Revisited---in memory of the late professor Shigeru Ishikawa Katsuji Nakagane (中兼和津次) Professor Emeritus at the University of Tokyo Email: knakagane@gmail.com Shigeru Ishikawa (1920-2014) Ishikawa’s contributions to the Chinese economic studies • Statistical analysis of China’s national income and capital formation (Ishikawa1960) • Macroeconomic analysis of China’s economic growth and structural imbalances based on Fel’dman=Domar model • Studies on intersectoral resource flows in China • Constructing an analytical framework for studies on economies with market underdevelopment Development of ISRF issue • The roles of agriculture in economic development and intersectoral resource flows (ISRF) • Lewis(1954)→Fei=Ranis(1964) →Ishikawa(1967) • Lee(1971), Mundle(1981), Ohkawa et al.(1978), Teranishi(1982) • Ishikawa(1990), Karshenas (1993) Agro-industrial relationship • Conventional wisdom: agriculture must provide industry with financial resources at the initial stage of economic development • Historical experiences: e.g. Japan after the Meiji restoration • Preobrazhensky’s proposition on socialist industrialization strategy---rural sector as a domestic ‘colony’ to provide the primitive accumulation for the national economy • Moreover, agriculture’s resource should be transferred to the state through skewed price mechanisms Ishikawa’s hypothesis • Ishikawa’s hypothesis: industry must aid agriculture in contemporary developing economies • Ricardian trap: underdeveloped agriculture→poor production of grains →rising grain price → increasing industrial wage → decreasing industrial profit → declining investment rate →declining growth → underdeveloped agriculture • Agriculture in today’s developing countries needs more infrastructural investment by the state or the industrial sector to escape from the trap ISRF and Ishikawa’s formula • ISRF between agricultural and industrial sectors (agricultural surplus): Xa-Xi where Xa is agricultural exports, Xi its imports • Real ISRF: S=Xa/Pa-Xi/Pi=(Xa-Xi)/Pa +(1/Pa1/Pi)Xi=(Xa-Xi)/Pa +(1-Pa/Pi)Xi/Pa where Pa is price index of agricultural exports, Pi price index of its imports, thus Pa/Pi is terms of trade for agricultural sector ・ Conventional wisdom: Xa-Xi>0, S>0 ・ Ishikawa’s hypothesis: : Xa-Xi<0, S<0 Estimates of ISRF in China • Several estimates of China’s ISRF have been made • Two types of estimates • Type A: Ishikawa(1967), Ishikawa(1990); Nakagane(1989) basically support Ishikawa’s hypothesis • Type B: Sheng(1993), Knight and Song(1999), Huang et al.(2006), Yuan(2010) deny the hypothesis Different approaches between the two types of estimates • Type A: based on official (planned) prices • Preobrazhensky’s proposition: Pa/Pi<1 • Type B: based on non-official, “appropriate” prices, which seem to reflect more correctly the real supply and demand relations than the official prices Type A estimates of China’s ISRF Example:Ishikawa(1967) Type A estimates of China’s ISRF Example:Nakagane(1989) Type B estimates of China’s ISRF Example: Knight and Song’s simulation • Their methodology: R*=pi*xi -pa*xa, where p* represents certain “appropriate price” • Preobrazhensky’s proposition: pi*<pi, pa*>pa • Procurement prices of agricultural products were highly underpriced, while prices of industrial products for the agricultural sector were intentionally overpriced Terms of trade between rice and selected industrial goods in Guangzhou and Hong Kong, mid-1970’s Ratio of free market prices to state procurement prices of grains, 1977-89 Simulation analysis: intersectoral resource transfers, assuming market price to exceed procurement price by 50,100, or 150% (Knight and Song 1999, p.239) Appropriate prices p* • What are the appropriate prices p*, then? • Market prices? • There are no sufficient data of market prices during the Maoist era, when any markets were squeezed and often shut down • Prices reflecting “labor values” inherent in the products ? (e.g. Li 1985) • But such prices are based on ambiguous assumptions about labor values Transactions under p* • If the intersectoral transactions had been made under the appropriate price system, the balance must have been as follows • R*=pi*xi -pa*xa • Hidden resource flows: R-R*, where R shows actual resource flows under the official (planned) price system, i.e. R=pixi - paxa • R-R*>0, since pi >pi* , pa*>pa as implied by Preobrazhensky’s proposition Question 1 • Agricultural products consist of many items. • Proportions of “price-skewedness ” of the agricultural products must be different by item • Thus, it must be wrong to obtain “appropriate prices” by multiplying a single correction parameter to the official planned prices • Furthermore, their approach does not consider “overpriced” industrial goods If world prices p* were available for major items of agricultural and industrial products • If no domestic market price data were available for the Maoist era, apply the world price to the calculation of ISRF for the same period. • Collecting both domestic and world prices of agricultural and industrial products for 19522000, Yuan (2010) concludes that China’s agriculture has long been taxed indirectly through the skewed planned price system Question 2 • If market prices were applied in simulation analysis, transaction volumes, too, must have been changed under these prices • Assume that every transaction were made by free market with p* • R^, or resource flow under the truly free market system, = pi*x*i -pa*x*a • Truly hidden intersectoral resource transfer, then, might be R-R^=0?, because x*i could be more than xi and x*a could be less than xa Ambiguous ISRF calculation • How much has agriculture provided China with its industrialization fund? • In what way did it provide the fund? • Through scissors' prices, or underpricing agricultural products as well as overpricing industrial products? • There seems to be no definite and exact way of ISRF calculation Undeniable facts and history • However, it is undeniable that Chinese peasants have contributed to the national capital formation, by sacrificing themselves with low income in collectivized agriculture, forced procurement, and hukou (household registration) system • Industrial workers, too, sacrificed their life under the “rational low wage” system during the Maoist era, but their sacrifice was much lighter than their counterparts in the countryside. See no starvation in the cities after the Great Leap Forward Significance of ISRF issue for today’s Chinese economy • Market economy has been expanding in rural China since 1978, as the procurement system was abolished in 1992 • Agricultural tax was abolished in 2006 • Hukou system has become relaxed • Last, but not the least, the share of agriculture in national income has been declining in China • However, as long as rural-urban divide exists, the ISRF issue still remains, though to a lesser extent • It must be a permanent issue until China’s economy is fully marketized, and the divided two sectors are unified in the true sense Acknowledgements • Thank you for giving me an opportunity to present my view today • Comments are welcome! Reference • • • • • • • Ishikawa, Shigeru (1965), National Income and Capital Formation in Mainland China---An Examination of Official Statistics, Institute of Asian Economic Affairs Ishikawa, Shigeru (1967), Economic Development in Asian Perspective, Kinokuniya Ishikawa, Shigeru(1967), “Net Resource Flow between Agriculture and Industry : The Chinese Experience”, The Developing Economies, Vol.5 No.1, pp. Karshenas, Massoud (1993), “Intersectoral Resource Flows and Development: Lessons of Past Experience”, in A Singh and H. Tabatabai (eds.), Economic Crisis in Third World Agriculture, Cambridge University Press Knight, John and Lina Song(1999), The Rural-Urban Divide: Economic Disparities and Interactions in China, Oxford University Press Lee, Teng-hui (1971), Intersectoral Capital Flows in the Economic Development of Taiwan, 1895-1960, Cornell University Press Li, Bingkun (1985), “Guanyu Jiandaocha dingliangfenxide jigewenti (Several problems concerning quantitative analysis of scissors prices) Continued-• • • • Mundle, Sudipto (1981), Surplus Flows and Growth Imbalances: The Inter-Sectoral Flow of Real Resources in India 1951-1971, Allied Publishers Private Ltd Nakagane, Katsuji. (1989), “Intersectoral Resource Flows in China Revisited: Who Provided Industrialization Funds?”, The Developing Economies Vol.7, No. 2, pp.146–173 Sheng,Yuming(1993), Intersectoral Resource Flows and China's Economic Development. Basingstoke: Macmillan Press; New York: St. Martin's Press Yuan, Tangjun (2010), China’s Economic Development and Resource Allocation 1860-2004 (袁堂軍『中国の経済発展と資源配分1860-2004』東京大学出版会)