Teaching Children to Read - Lake Stevens School District

advertisement

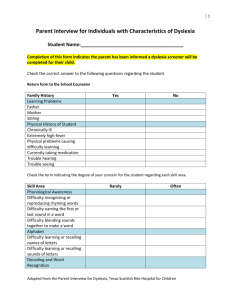

Dyslexia Teaching students with receptive and expressive language impairments in the oral and written language modalities Contents 1. What is Dyslexia? 2. Identification, diagnoses and treatment considerations? 3. What are some ways to approach treatment? 4. Answering questions… Definition… Dyslexia is defined by the National Institution of Health (NIH) as “a brain-based type of learning disability that specifically impairs a person's ability to read.” In general, most individuals with dyslexia: Typically read at levels significantly lower than expected despite having normal intelligence. Dyslexia is often referred to as a language based learning disability. Individuals with dyslexia usually have difficulty with either receptive oral language skills, expressive oral language skills, reading, spelling, or written expression. Research Based Facts Dyslexia is the most researched of all learning disabilities. Dyslexia affects at least 1 out of every 5 children in the United States. Dyslexia affects as many boys as girls. Dyslexia is the leading cause of reading failure and school dropouts in our nation. Reading failure is the most commonly shared characteristic of juvenile justice offenders. Characteristics It is characterized by difficulties with accurate and/or fluent word recognition, and by poor spelling and decoding abilities. These difficulties typically result from a deficit in the phonological component of language that is often unexpected in relation to other cognitive abilities and the provision of effective classroom instruction. Secondary consequences may include problems in reading comprehension and reduced reading experience that can impede growth of vocabulary and background knowledge. Question 1: “Can you be a little or a lot dyslexic?” Dyslexia varies in degrees of severity. The prognosis depends on the severity specific patterns of strengths and weaknesses appropriateness of the intervention It is not a result of lack of motivation, sensory impairment, inadequate instruction, environmental opportunities, low intelligence, or other limiting conditions. It is a condition which is neurologically based and often appears in families. Occasionally, dyslexia can be misdiagnosed when vision deficits are involved. Question 2: “Is it spectrumish?” This question leads to the discussion of emotional/behavioral consequences of reading deficits…. Other disorders that may co-occur include: Attention deficit disorders Autism spectrum disorders Auditory processing deficits Seizure disorder Children with Language Learning Differences (multilingual backgrounds) may also have dyslexia Others Question 3: “Is dyslexia hereditary?” Answer: Some forms of dyslexia are highly heritable. (Excerpt of an article in the American Journal of Psychiatry published in December 2008 on www.ajp.psychiatryonline.org) Dyslexia Susceptibility Gene The results of this study both support the role of K1AA0319 in the development of dyslexia and suggest that this gene influence reading ability in the general population. Moreover, the data implicate the three-SNP haplotype and its tagging SNP rs2143340 as genetic risk factors for poor reading performance.“ 2005-2008 Research Highlights… “Dyslexic children use nearly five times the brain area as normal children while performing a simple language task” (2005) (e.g., Detour to MP) Dyslexia “…may be caused by disorganized, meandering tracts of nerve fibers in the brain” “making it difficult to integrate the information needed for rapid, ‘automatic’ reading.” (2007) “Key areas for language and working memory involved in reading are connected differently in dyslexics” (2007) Intensive “…remedial instruction resulted in an increase in brain activity in several cortical regions associated with reading, and that gains became further solidified during the year following instruction” (2008) “…Once the children with dyslexia received an intense and specialized instructional program, their patterns of functional brain connectivity normalized.” (2008) 2008-2010 Research Highlights… Preschool predictors of reading and writing difficulties were identified in two contexts: a delayed ability to detect and process voices, and slow naming of familiar, visually presented objects (2008) A moderate and stable relationship was found in phenotypes between 4-year speech and language scores and reading at 7, 9, and 10 years (2009) Results support the notion that letter-speech sound integration is an emergent reading skill that develops inadequately in dyslexic readers, “presumably as a result of a deviant interactive specialization of neural systems for processing auditory and visual linguistic inputs.” (2010) Conclusions 1. Dyslexia is a brain-based disorder. 2. Timing of connections have a significant affect on processing language. 3. White matter in the brain can be altered. The earlier this happens the better. 4. "Focused instruction can help underperforming brain areas to increase their brain proficiency." 5. Both genetic and environmental factors contribute to the relationship between early language skills and reading, whereas genetic factors play a dominant role in the relationship between early speech and reading. Early Intervention Begins in Preschool Individuals with dyslexia respond successfully to timely and appropriate intervention. Children as young as 4 1/2 can be diagnosed with dyslexia. Dyslexia is identifiable, with 92% accuracy, at ages 5 1/2 to 6 1/2. Red Flags Begins with: Poor expressive & receptive language skills Poor listening, processing & organizational skills Lack of print knowledge Poor phonological awareness skills But, often, it is spelling that separates kids with dyslexia from kids who struggle with reading for some other reason. (See a list of additional red flags in the addendum) Directionality Most dyslexic children and adults have significant directionality confusion. Left-Right confusion: Even adults have to use whatever tricks their mother or teacher taught them to tell left from right. It never becomes rapid and automatic. A common saying in household with dyslexic people is, "It's on the left. The other left." That's why they are b-d confused. One points to the left and one points to the right. They will often start math problems on the wrong side, or want to carry a number the wrong way. (e.g., Hannah) Up-Down confusion: Some children with dyslexia are also up-down confused. They confuse b-p or d-q, n-u, and m-w. “My kid reverses…. Is he dyslexic?” Confusion about directionality words: First-last, before-after, next-previous, over-under Yesterday-tomorrow (directionality in time) North, South, East, West confusion: Adults with dyslexia get lost a lot when driving around, even in cities where they've lived for many years Often have difficulty reading or understanding maps. Who can identify and diagnose? Anyone can identify a child with dyslexia Knowledgeable Informed Who can provide a diagnosis? Washington State DOH indicates only licensed and trained: Physicians Psychologists Speech-language pathologists Why test for dyslexia? Why is an evaluation important? better understand the problem determine eligibility for special education services in various states also determine eligibility for programs in colleges and universities provide a basis for making educational recommendations determine the baseline from which remediation programs will be evaluated The Numbers… Very few children with dyslexia are in the special education system. Only 1 in 10 will be eligible for an IEP (when tested in second or third grade) under the category of Learning Disability (LD). That means 9 out of 10 may "fall through the cracks." Although the parents and the teacher know there's something different about the child, the child does not qualify for special education services, and most will no longer get help from the reading specialist after first or second grade. Dyslexia is not rare. It is the most common reason a child will struggle first with spelling, then with written expression, and eventually "hit the wall" in reading development by third grade. Testing Individuals may be tested for dyslexia at any age. Tests which are selected will vary according to the age of the individual. Young children may be tested for phonological processing, receptive and expressive language abilities, and the ability to make sound/symbol associations. When problems are found in these areas remediation can begin immediately. A diagnosis of dyslexia need not be made in order to offer early intervention in reading instruction. Treatment Considerations Acquisition of letters and their sounds for reading and writing typically mirrors developmental norms for speech sound acquisition When you’re choosing materials and what to focus on with an individual, keep this at the forefront (See normative data chart in addendum) Phonological Awareness Broader Narrower (top down) 1. Identify… 2. Use… oral rhymes syllables in spoken words cup, sup, tup cupcake = cup + cake onsets & rimes in spoken syllables individual phonemes in words spoken cup = c + up cup = c+u+p Phonemic Awareness Increases word reading increases reading comprehension Increases reading fluency -through blending Increases strategies for accurate spelling -via segmenting -predictable relationships Sound Segmentation Sentence segmentation – nursery rhymes, famous songs, etc. (only if they can interpret information at this level) Word segmentation Syllable segmentation Phoneme segmentation 1. 2. 3. 4. “Count how many sounds you hear in the word “boat”. Remember to sound them out!”; not, “How many sounds are there?” b-o-t = boat What sound does letter B say? Or B says /b/… but help them distinguish between the name of the letter and the actual sound it makes. The answer is not “bee”, it is /b/. How many sounds do you hear in B? (2?, 1?) vs. How many sounds does letter be make/say? (1? 2?) Help the students identify and catalog how many sounds certain letters make and in what combinations (e.g., “What letters spell /i/ or /ai/?”) Continue teaching letter names vs. sounds letters make for CV, CVC, CVCV, CCVC, and CVCC words SLPs building strong phonemic awareness skills Identifying sounds Start with counting the number they hear in a CVC word, then contrast with CV or VC If they aren’t getting it, I often go to: “How many sounds do you hear in the letter…M?” /m/ or “e-m” ; /k/ or “k-ay” Do for first, middle and last sounds within words (e.g., Tell me the first sound you hear in “cat”) = /k/ Isolating sounds (e.g., Say “cat” without saying “at”) = /k/ Try manipulables (pompoms, colored squares, etc.) for support; take away to increase the demand SLPs building strong phonemic awareness skills Categorization of sounds Choppers (“ch”, “j”), poppers (t, d, k, g), air sounds (s, f, v, “sh”, “zh”), lip sounds (m, p, b, w), tongue sounds (l, r)… Blending sounds “I’m going to tell you some sounds that make a word. What word can you make with these?” /a/-/t/ = at Onsets/rimes CV, CVC, CVCe, CVCV, CCVC, CVCC, CVCVC and so on… Deletion & Addition Sentence level: (when they are reading sentences) Try working with adjectives and adverbs (e.g., “He ran softly and quickly.”) Phrase level: (when they are reading phrases) Name Game; Mad Libs, fill in the blank (e.g., auditory closure tasks), wacky words (combine 2 juxtaposed words in a silly phrase) Word level – TYPICALLY, I START HERE Syllables: Compound words (cowboy, cupcake, pigpen) Try using affixes (-er, pre-, re-) Deletion & Addition Phoneme deletion (initial, medial, final positions and consonant clusters) “Say cup with out saying /k/.” “Say tired without saying /d/.” Phoneme addition Incorporate morphology instruction (-s, -es, -ing, -ed) Add /s/ to the beginning of top it becomes…” “Add /t/ to the end of goes, it becomes…” Substitutions 1. Word substitution (the name game) 2. 3. Syllable substitution (the other Name Game) Phoneme substitution 4. Alicen Lea Burke Change “Lea” to “Fizzle” Now change Burke to “Pop” “Say ‘hat’. Now, change the /h/ in hat to a /s/.” Sentence and Phrases can be addressed later Building Strong Skills Work on only one or two targets with individuals at a time. Work through a hierarchy for each target. When they’ve mastered all the domains, you should be able to have them mix 2 domains, 3, and then all in any order. They will not achieve independence until they effectively master multiple targets at once. Language use/presentation is key to helping them understand! Setting Them Up for Success Through Specific Language Use The obscurity of the letter name and the sounds letters make… “What sound does B make?” vs. “What sound does letter ‘B’ say?” Bee or /b/? Letter B says, “/b/.” “How many sounds are there in the word ‘bush’?” “How many sounds do you hear in the word ‘bush’?” b-u-sh; bu-sh; b-u-s-h Common Errors When confusion of letter name vs. phonemes heard is not corrected at the sound level, it will continue to confound the young reader and writer at higher linguistic levels. (e.g., fractions) Compensatory strategies adopted by the student: Using knowledge about the context of the content to guess Using reasoning skills to guess more accurately Searching their environment for clues Guessing (random or methodical) Consequence: Students often start off behind in spelling and later in reading comprehension and fluency. Teach Awareness Strategies Start out teaching rhyming with long, familiar words instead of short ones (e.g., peanutbutter) Vowel pacing board with explicit teaching Provide tactile cues if needed when segmenting Consonants vs. vowels identification Chart sound families (use like a dictionary) Chart word families as they progress through levels Chart common letter sequences within words, affixes in English (e.g., ng, str) Hierarchical Support Systems (e.g., Words Their Way) Use a hierarchy of support to ensure success. Explicit teaching Identification Matching Sorting Sequencing Fill in the blank Independent Give consistent, intermittent positive feedback! More… Student to identify and chart “hard” words; are there trends? Visualizing; Does it look funny? Choral reading (let students lead?) Keep a vocabulary list of new words; define them on 3X5s for early study habits and games (e.g., Arrange by letter/sound Arrange by category Parts-of-a-whole Sound segmentation Include gross motor movement during reading and spelling Involve the cerebellum! Use jump rope, Chinese jump rope, Mother May I, Simon Says, word pop-ups, sound pop-ups, four square, hopscotch, Hullaballoo) Management and Accommodations Richelle to add Procedures for Referral at Sunnycrest… If it’s speech only… refer to the SLP If it’s language in any form, refer to the team If it’s highly likely the child will not qualify and you don’t think it’s “worth it” to refer to the team, use your resources and talk to the parents about self-referral for literacy assessments. Questions you asked Is it hereditary? Is it spectrumish? Can you be a little or a lot dyslexic? What are the red flags that we should be looking for? "My kid reverses b/d or some other letters and numbers. Does that mean they are dyslexic?"; "My kid will be reading words like "was" and say "saw" instead. Do they have dyslexia?" When are children typically diagnosed with dyslexia? Is there a window of opportunity for intervention, or can it be addressed at any age? Can it be confused with other disabilities or can a professional confidently diagnose it? Where can they be tested? What can teachers do to help a student with dyslexia that is not succeeding in the regular ed. classroom, but does not qualify for special ed. services? Are there research based interventions that work for everyone? What resources are available from the Lake Stevens School District for the classroom teacher to aid in the teaching of a dyslexic child? What can we do in the classroom to provide help? Are there good resources out there that we can let parents know about? Resources Seattle/King County Hearing Speech and Deafness Center (HSDC), Seattle Branch (Noreen Bucknum, MA, CCC-SLP) UW and possibly WSU run summer literacy camps Commercial programs Snohomish SLPs, SPED teachers in LSSD Local research based programs: Language to Literacy Program, provided at HSDC (BSHC) Julie Sewald’s early intervention Tutorial Program References and Citations Keller & Just (2009). Altering cortical connectivity: Remediation-induced changes in the white matter of poor readers. Accessed from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20005820 Bright Solutions for Dyslexia, Inc. http://www.dys-add.com/symptoms.html. Accessed April, 2010. Marshall & Messaoud-Galusi (2010). Disorders of language and literacy: Special issue. Accessed from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20306622 Blau, V., Reithler, J., van Atteveldt, N. & Seitz, J., et al. (2010) Deviant processing of letters and speech sounds as proximate cause of reading failure: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study of dyslexic children Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research Vol.53 311-332 April 2010. doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2009/07-0145) Accessed from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20061325 Mayo Clinic dyslexia information page. Mayo Clinic. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/dyslexia/ds00224/dsection=symptoms. Accessed April, 2010. NINDS dyslexia information page. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/dyslexia/dyslexia.htm. Accessed April, 2010. What are the signs of dyslexia? International Dyslexia Association. http://www.interdys.org/SignsofDyslexiaCombined.htm. Accessed April, 2010. Catts & Kamhi (2005). Language and Reading Disabilities. (Ed. 2). Boston, MA: Pearson, Inc.