Fiction Crash Course

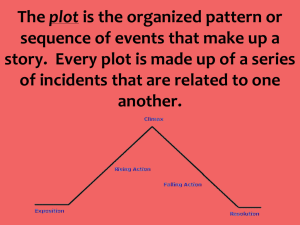

advertisement

Andy S: how did you load/post your flash fiction? Can’t open it. I want an end to these Bb glitches! Next Week All semester cyber work to date must be ready for a check by class time. If you want to revise anything, or post a late assignment, you have until March 4th. After that we begin a new check period. I’ll do two or three checks over the semester. Remember each week to check the Weekly Cyber Class Instructions forum, as well as the online schedule and any new and/or updated Power Point presentations. Also for Next Week • Read Sebold stories: Alice Fulton, “A Shadow Table” and Alex Rose, “Ostracon.” • Workshop. • Project #2 due March 11 (I’ll get some draft feedback to you within a few days) Interested in Writing Fiction? A Crash Course in Creating Characters, Plot and Setting First, a quick review of a couple important points… What is the difference between an essay or a work of expository prose and a story? Essays generally have a thesis, are primarily factual and reflective (not dramatic), are “narrated” by the actual author, and are usually structured as traditional, a-temporal arguments. Stories don’t have a thesis, are primarily dramatic and fictional, are narrated by an invented character, and have temporal structures. Don’t confuse a firstperson narrator of a story with the author of the story! They are not (necessarily) the same person! Note that experimenting with plot is one of your options for Fiction Project #2 Ok. Plot What is it? How do you make one? How do you make a GOOD one? Plotting a Story What's a plot? o When this question linked is to CHARACTER, you have a stronger, richer story! The sequence or pattern of events in a story. “First this happens, then that happens, then this…” What sets a story in motion? o o A QUESTION is posed, explicitly or implicitly. So why do you continue reading? What keeps you turning pages? You want to know the answer! Thinking about “The Narrative Question” A guy is climbing a mountain. What’s the narrative question? Right: will he make it to the top? What are the possible answers? Yes or No Nothing wrong with a story like that; it can be quite good. But you can do a lot more with plot. Suspense and interest can get REALLY intense when ADDITIONAL questions are introduced in the course of the plot. Two guys are climbing a mountain. One is having an affair with the other guy’s wife. More questions What’s the narrative question(s)? • Will they make it to the top? • Will one make it and the other fail? • Will one find out that the other is having the affair? • What will happen when he finds out? and/or more possible answers = more suspense! There are other ways of thinking about what sets a plot in motion and keeps it moving. A balanced situation becomes… unbalanced! Some sort of equilibrium is disturbed. An obstacle is presented. The more obstacles, the more potential suspense. Usually :) Another way to think of PACE, in fact, is the RATE OF REVELATION. What else is important to plot? PACE What speeds thepace? slows the Exposition. pace? Interior monologue. • ACTION! Description. • Revelation of Dialogue. Sub-plots or parallel plot ANSWERS to(more the on this is just a sec) narrative False clues, misdirection, or otherwise questions withholding answers to the narrative question. See class notes (material on board) for details Helpful Plot Devices Framing (we’ll talk about this more in a sec) Flashbacks Foreshadowing Parallel or intersecting plots or sub-plots (more in a sec) False clues “Hooks” (these are not so much “devices” but integral elements; sometimes they’re referred to as complicating actions, triggers, or twists) Delay (withholding answers to the narrative questions) Plot Structure What’s the shape of your plot? How do its parts fit together? Hook = “triggering action” or “complicating action” or “narrative question” or “twist.” Different sources will call these by different names. False clue Increasing tension X Partial answer X Introduction of minor parallel plot X X X Flashback TRADITIONAL PLOT STRUCTURE: standard rising and falling action What SLOWS Pace? X X X X X X What SPEEDS pace? ACTION! ANSWERS! Scene-setting (exposition) Dialogue. Internal monologue. Description. Resolution Nothing wrong with a traditional plot structure. And did you know: each carries with it its own ideological assumptions about the nature of time, desire, purpose, even human existence itself? Authors and titles mentioned here are class assignments or material you can easily look up. Alternate Plot Structures Different plots Framed narrative. (Or this is actually a plot device.) Have you seen can express Titanic? alternative Montage or collage. O’Brien story? ways of experiencing Multiple and intersecting plots. Continental Drift. TIME and Chronologically backwards plot. (Yes—backwards. See Lorrie Moore’s REALITY! See “How to Talk to Your Mother.”) Gabriel Garcia StaticMarquez’s plots. (See experimental stories by Robbe Grille.) One Hundred Years All flashbacks, or footnotes, or exposition. Nicholson Baker’s, The of Solitude. Mezzanine. Tim O’Brien’s, “How to Tell a True War Story” What do you make of PLOT in this story? Plot Thingys to Avoid The “it was all a dream” ending. (Besides the fact that it already happened to Dorothy, it’s just a cheap solution to the difficulties raised in the story.) Suicide endings. (Sorry—your characters will have to find some other way out of their problems. Avoid this kind of ending at least for now.) O’Henry twist endings. (Clever, but get old fast. The twist becomes the whole point of the story, and ultimately has limited interest.) Tidy, comprehensive endings in which everything comes out well, all loose ends are neatly tied up, and the universe is pretty much explained to one and all. Let your stories end inconclusively now and then. Let them end with questions rather than answers. Something to Think About Does a story have to be plot-centered? NO! A piece can be character-driven, image-driven, idea-driven, even setting-driven. (Look at selected scenes from Robert Altman’s, The Player.) So, a little sum-up: Plot—Don’t Plod! o Be aware of your narrative question. Introduce additional narrative questions. Create multiple obstacles, physical or emotional. o Control the rate of revelation. Slow pace = interior monologue, description, dialogue, exposition. Fast pace = action, jump cuts, answers to narrative question. o Provide false clues, misdirection. o Develop sub- or parallel-plots which delay revelation in the main plot, add interest and complexity. o Consider creating your backstory gradually. Don't give main character’s full story immediately. Let it evolve. o Provide powerful IMAGERY which heightens tensions. Students almost NEVER use imagery with feeling. Note: many students are not aware of where their scenes stop and start, and their transitional passages are consequently “muddy”: overelaborated, bogging the whole story down. What else is important to plot? Scene Development o A unit of time and place in which (usually) important action takes place. o Can be like mini-stories within the larger story. Scene transitions o o o Provide a simple extra space on the page. This is common these days. Transitional phrases. “Jump cuts.” Leaping from one scene to another abruptly. Done well, reader intuits the transition. Student stories often have needless exposition and crud between scenes. How long should a scene be? Depends on length of story. Depends on pacing: do you want to speed things up or slow things down? Short scenes obviously go faster than longer ones. Student scenes are often neglected. Too long, too short, non-existent… What do you make of the dinner scene in “Cathedral”? Characters How do you make them? How do you make them INTERESTING? Types Flat (or Simple, Secondary, Static) Round (or Complex, Primary, Dynamic) Need to Be Try starting with a CHARACTER idea, not a plot idea! Believable, Real Consistent Distinctive Worst beginner faults: characters who are all alike (can’t tell one from the other), or are generic. Starting with a Character Imagine-up a distinct, rounded, believable person. What is that person’s main faults? Greatest fears? Worst neuroses? What makes this person nervous, edgy, confused, repulsed? What do they NOT KNOW about themselves? NOW: put that character in a setting and situation which will MAXIMAZE his/her fears, faults, neuroses; a situation which may force them to confront their what they do not know about themselves or what they don’t want to know. EXAMPLE: “CATHEDRAL” Well… • He’s not a genius. • He’s not very worldly. Limited experience. • He’s put off by what is different. Narrowminded. Kind of a xenophobe. • He’s not especially ambitious. • He’s a bigot. • He’s left-brain oriented. • He’s not really a bad guy, just a dope? How does Carver handle those questions, and what is the outcome? applied to CHACTERIZATION Let only the tip of the iceberg show—the right details will evoke the great complex mass of what lies beneath. In other words: show—don’t tell. Provide fewer, but better, details. (Less is more.) Don’t explain your protagonist’s feelings or issues away; reveal their character dramatically: o o o Have the person do something which reveals interesting nuances of their personality. Have your character react to what someone else does or says. Show other characters reacting to, or speaking about, your protagonist. Silences aren’t silent. Silences aren’t nothing. Being good with words means knowing when to shut up. Sometimes it helps to LITERALLY sketch or draw the character! Try a verbal “character sketch”… I.e., invent someone… My character’s name is X and she is an X. She’s from X and first Xed when she Xed… a person who will be with you the rest of the semester. You can explain many things, but try to describe more than explain. At least 3 paragraphs. Can be notational. Now look again at your character sketch. What were you doing? Your character is FLAT! BORING! GENERIC! 2-dimensional! Look at questions in Harmonious Confusion and TRY AGAIN bonehead! www.ndsu.nodak.edu/instruct/cinichol/CreativeWriting/323/HarmoniousWhole.htm Don’t feel you have to know everything there is to know about your protagonist! In fact, if your protagonist is any good, you WON’T know everything there is to know about the person. SETTING and IMAGERY What do SPECIFIC ITEMS in the setting say about the main character? – – – What is in your invented character’s bedroom? What is in YOUR bedroom? What is in the jungle in “How to Tell a True War Story”? What is in the home of the protagonist of “The Cures for Love”? What mood is created by the setting and by the story’s imagery? How do the setting and the imagery contribute to theme? In what ways might a story actually be ABOUT setting? (setting that is almost a character) Settings which tell us very GENERAL kinds of things about the characters (socio-economic class, general historical time and location), though some are at least evocative) These tell us more about the specific individuals living in them And now… Fiction: Again, Some #1 Things to Look Out For Before handing in workshop material, ask yourself at least a few of these questions: 1. Does the story rely entirely on plot? Are other story elements—character, setting, perspective, language, image—ignored? 2. Does the plot in turn rely entirely on an "O'Henry twist" or trick ending? This is fun maybe once or twice, but it gets old really fast. You should only be doing this sparingly. The outcome is a foregone conclusion for the writer and so no discoveries have been made. One of the central pleasures in writing—for the writer—has been missed. 3. A related problem is the plot based heavily on a clever, "ooh-aah" or "oh wow" premise. Such a premise or basic concept is fine if the story is otherwise fully developed, but too often the premise becomes the only point, a gimmick of interest for about 3 seconds. Try founding your story on some interesting and unresolved, possibly unresolvable problem of character rather than plot. The premise may seem less snappy or clever at first, but ultimately the story will be richer and take the reader (and you, the writer) into more interesting territory. 4. Is the plot "front-heavy"? That is, does it have page after page of initial scene-setting and exposition, followed by screaming slide to a conclusion? 5. Is there a suicide ending? Come on. 6. Are there plenty of specific, concrete, sensory DETAILS so that the reader can really see and feel the setting and characters? Or is most of the language general and abstract? 7. Are the characters in the story distinctive? Can you tell one apart from the other, or are they all basically the same person? 8. Are the characters developed? Do you really know the central people in the story—their desires, physical quirks, beliefs, contradictions? Does the main character leave an impression? Do you know everything there is to know about the main character? (you shouldn't!). 9. Are scenes* in the story distinctive and delineated? If they all kind of run together, chances are there's a lot of inconsequential action which is diluting the best stuff so we can't see it or experience it vividly. Go through and mark where scenes in the story begin and end, and consider cleaner transitions from one scene to another. 10. Look at the scenes you've marked. Is each one sufficiently developed? Notice where some good scene opportunities are being brushed over. These are places where you probably SUMMARIZED or used EXPOSITION rather than developed the moment with sensory detail. 11. Are the scenes well-modulated? You want to alternate action, reflection, dialogue, and exposition—not action scene followed by action scene followed by action scene. If there's no modulation, the high points just run together with the low points and the story will feel monotonous. 12. Is the point of view modulated? You want "distant shots" as well as detailed "close-ups." 13. Is there real engagement with language? Or, oops, is the prose style pretty much a soggy paper towel? 14. Look out for dull, hackneyed language; cliché words and expressions: a. b. c. d. e. f. g. h. "sly smile" "evil smirk" "deep into his eyes" "heart leaped to his throat" "face etched with concern" "blacker than night" "bitter tears" majestic sunset," etc. 15. Try some interesting figurative language! Look at Lorrie Moore and Annie Proulx for evocative, surprising, moving, vivid, juicy metaphors and similes. 16. Watch out for monotonous sentence length and style; no rhythmic, modulated, or otherwise engaging sentences. 17. Listen for voice—does your narrator, whether she's wholly omniscient, limited omniscient, or first-person—have a distinctive way of talking? * Scene = an unbroken stretch of time and action, usually in one place. Unlike a summary or exposition, which may overview a broad period of time, a scene generally covers a brief, detailed, circumscribed period. Scenes are almost like small stories in themselves. Copyright A VERY Brief Look at a TINY Number of Issues Idea-Expression Dichotomy You can’t own an idea… but you can own the original expression of an idea. “[T]he ‘ideas’ that are the fruit of an author's labors go into the public domain, while only the author's particular expression remains the author's to control” (http://www.edwardsamuels.com/copyright/beyond/articles/ideapt1-20.htm). “Given the difficulty of defining the terms of the doctrine, some courts and commentators have developed an ‘abstractions’ test[FN6] or a ‘patterns’ analysis,[FN7] which purports to place a given work along a continuum between idea and expression. Although it is impossible to state precisely when a particular work has crossed the threshold from one end to the other, the courts are nonetheless supposed to struggle to apply the terms.” Ibid. Other Considerations “Substantial Use” “Fair Use” “Sufficient originality” Commercial Screenwriting Movies vs. Plays vs. Novels Novel: author has control of nearly all of the main product Plays: playwright has total control of script Movies: screenwriter usually has little control of anything Novel: can get directly into characters’ thoughts and also provide exposition easily Movies: primarily visual Plays: primarily verbal (dialogue) Novels: a solitary art Plays and especially movies: highly collaborative arts Basics BASICS Shooting BASICS or Production Script: Formatted for actual use on set. And there’s the: Pitch Outline Spec or Writer’s Script: Treatment Synopsis For shopping your script around. 100-120 pages. Period. In MANY commercial films, CONCEPT is key. A successful concept: Can be understood by an 8th grader Can be summed up in one or two sentences Is provocative Provides a compelling mental picture Has a main character who experiences a conflict which leads to an initial HOOK Has sequel potential Has “legs” (could work even without big stars) Will nonetheless attract a big star Stands out Is original but also has familiar elements (Being John Malkovich) You can see the whole movie in it Has broad appeal Is marketable; the exec knows immediately that the idea has potential Formulating the concept (the “one-line” or “logline”): Pose as question: What if Dorothy had a sister? What if Titanic were a spaceship instead of a boat? What if one of the ghostbusters were himself a ghost? Pose as a logline: TV Guide or newspaper movie section one-sentence summary Pose as a hook: The Graduate: Part II Out of Africa meets Pretty Lady Braveheart comes to America (The Patriot) Night of the Living Dead meets Star Wars (The Imposter) Night of the Living Dead meets Outbreak (The Invasion) Animal House meets The Good Girl (The Tao of Steve) Logline should have an implied structure—on hearing the concept, an exec would sense a beginning, middle, and end, or the “beats”: 1. Opening Image Every handbook you consult will 2. Theme Statement break these parts down a little 3. Set-up differently or with different headers 4. Catalyst 5. Debate 6. B Story (usually the love story, page 30) 7. Fun and Games 8. Midpoint 9. Bad Guys Close In 10.All is Lost 11.Dark Night of the Soul 12.Finale 13.Final Image The killer TITLE + the CONCEPT = a one-two Know Your Genres Thriller Love Story Action/Adventure Sci-Fi Horror Detective mystery Comedy …including ones not mentioned in your local video store: The Fish Out of Water Dances with Wolves, Dangerous Minds, Miss Congeniality, Legally Blonde, Benjamin Button, The Reader The Pet Who Heals Winn-Dixie, Seabiscuit, As Good as It Gets (sub-theme), Marley and Me The Buddy Story (Sensitive Male Bonding Flick) Ill-Fated Lovers (Casablanca, Romeo and Juliet, Plain Jane Transformed The Devil Wears Prada, Pretty Lady, My Fair Lady, Cinderella (of course)… Beloved Mentor Dead Poets Society, Dangerous Minds, Good Will Hunting Rites of Passage (A Few Good Men, Rocky, Titanic, The Reader) The Quest (Titanic, Troy, Indiana Jones, My Best Friend’s Wedding Monster in the House (The Exorcist, Tremors, Panic Room, Alien) The Brilliant Dope (Forrest Gump, Dave, I Am Sam) There is much, much, much, much, much, much, much, much, much, much, much, much, much more to this discipline. I’ve given you a wee taste, a feel for the commercial foundations. Finding resources is EASY To read actual film scripts, try out: www.isriptdb.com (Internet Movie Script Database) www.dailyscript.com www.newmarketpress.com/category.asp?id=10www.scriptcrawler.com (New Market Press’s film and television scripts for sale) www.script-o-rama.com www.simplyscripts.com TV and movie script writing site: www.cybercollege.com/index.htm Quicky on film script format: www.cybercollege.com/dram_flm.htm Longer thingy on script writing format: http://www.screenwriting.info/ These sites haven’t been thoroughly examined; they are suggested starting places only. BTW, how do you know when a website is junk? No contact info or verifiable background No affiliations, stated or linked Claims made without supporting evidence The site is problematically “.com” or other “.orgs” are getting easier to fudge, apparently No documentation of sources No documentation of little-known or debatable info Conspicuous ill-will, bias, disregard for opposing views Unedited and unproofread Links take you to advertisements or porn Comes from Wikipedia :) Wickedpedia There’s a whole world of non-formula filmmaking and screenwriting out there; you just might have to look a little further than franchise theaters or screaming TV trailers. E.g., visit the Fargo Theater! But, man, do you really want to write formula stuff? The Snow-Munching Exercise: What’s the Story? Where to? • • • • • • Possible pts. of view: – You – Teacher – Onlookers – Classmates Point of entry – Instructor giving assignment – You on your way – Teacher waiting – Snow in the mouth – Someone reflecting back (frame) Narrative question: – What will it feel like? (action story about people in conflict, danger) – What will happen to me when I do this weird thing? Can I make myself do it? (character-based story about personal growth; tiny coming-of-age piece) – Why is instructor doing this? (story about education; maybe mentor-piece; battle-ofwills piece) – What will students think of this assignment? (the burned-out teacher; the evil teacher; the heroic teacher) Triggers, hooks, complicating actions, mounting tension – Dialogue with other students on the way – New thoughts on the way – Diversions; delays; false leads – Setting: how do things LOOK when one is stepping directly into the unknown? Climax Dangers of this story – Pat theme More on Fiction Coming Soon! Screenwriting info freely cribbed from Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat, Linda Seger’s From Script to Screen, David Trottier’s Screenwriter’s Bible, and Skip Press’s The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Screenwriting and Rob Tobin’s The Screenwriting Formula.