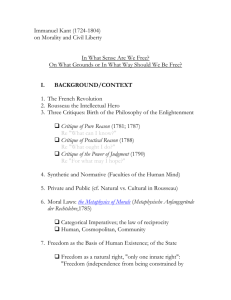

Cultuurfilosofie college 9

advertisement

The Heritage of Kant’s Work in Recent French Philosophy April, 3: Lyotard Introduction 1 Jean-François Lyotard: • Born 1924 near Paris • After finishing his study he taught philosophy in Algeria 1950-52 • Member of a marxist group around the journal Socialisme ou Barbarie (Castoriadis, Lefort) 19541964, Pouvoir Ouvrier 1964-1966 • After his book Phenomenology (1954) until 1966 only articles in Socialisme ou Barbarie, mainly on the struggle for independence in Algeria, under the pseudonym François Laborde – no philosophical publications • In 1968 teacher at the University of Nanterre, where the French May 1968 revolt of students and workers began • Dissertation in 1971 • Some fame as postmodern philosopher since 1979 • Died 1998 Introduction 2 Most important works – original publication in French / English translation • Phenomenology (1954/1991) • Discourse, figure (1971, dissertation/2011) • Libidinal Economy (1974/1993) • The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge (1979/1984) – in the English edition the essay ‘Answering the Question: What is Postmodernism?’ (1982) is added • The Differend (1983/1988) • ‘Judiciousness in Dispute, or Kant after Marx’ (1985/1987) • Enthusiasm. The Kantian Critique of History (1986/2009) • Heidegger and ‘the jews’ (1988/1990) • The inhuman. Reflections on Time (1988/1991) • Lessons on the analytic of the sublime: Kant’s Critique of Judgment §§ 23-29 (1991/1994) Political Writings (in English, 1993) Most of his works on art reappeared in the bilingual (French/English) Writings on Contemporary Art and Artists (Leuven University Press): six volumes, amongst others on Appel, Francis, Duchamp, Adami, Arakawa, Buren, Monory From libido to justice His first works after his return to academic philosophy (Discours, figure and Libidinal Economy) manifest a philosophy of difference, criticizing both phenomenology and structuralism, influenced by Nietzsche, Derrida, and Deleuze, and mainly based on a reading of Freud • Some key words: energy, drives, intensities, transgression, affirmation, unconsciousness as work, the work of art • ‘Not an ethics is required. Perhaps we need an ars vitae (…) one in which we would be the artists ’ At the end of the 70’s Lyotard explicitly takes distance from these works / a shift towards Kant • His own later comments: ‘I had not yet recovered from the temptation of indifference’, later works ‘try to say the same, but without unburdening themselves so easily from the problem of justice’ • The first work in which this shift can be noticed: Au juste, 1979 (Just gaming, 1985) • Kant’s ethics, but also his aesthetics ‘Answering the Question: What is Postmodernism?’ • • The title is an allusion to Kant’s essay: ‘Answering the Question: What is Enlightenment?’ (1784) But it is mainly a reaction to Habermas: ‘Modernity – an unfinished project’ (1981) Lyotard reads Habermas as imposing on art the task of contributing to more unity in society Unity? A. an organic whole, dialectic totality = Hegelian, or B. a path between heterogeneous language games? • Lyotard takes up B ~ Kant’s Critique of Judgment – although postmodernity submits to a severe reexamination: 1. The thought of the Enlightenment 2. The idea of a uniform end of history 3. The idea of the subject Lyotard/Kant Habermas/Hegel • Lyotard’s main argument against Habermas’s project of modernity is that it needs art to be based on the concept of beauty (recognizable, representation) so that it ignores experimental avant-garde art, which is based on the sublime (as in Kant’s aesthetics: no harmony between sensibility and reason, therefore no recognition) Lyotard’s first big question: unity (here: in society, between art and society, within the work of art, within the subject) Enthusiasm 1 • Lyotard’s most important work The differend (1983) contains 14 ‘Notices’, interrupting the main text, mostly on philosophers relevant for Lyotard’s argument in that section of the book. Most attention is paid to Kant: four long Notices. Kant Notice 3 and 4 are nearly identical to parts of Lyotard’s book Enthusiasm. The Kantian Critique of History (1986) Lyotard focuses on Kant’s third Critique, the Critique of Judgment, because critique is judging under which jurisdiction (which faculty) a certain specific claim (statement, phrase) belongs • Kant’s reflective judgment: only the particular is given, for which the universal is to be found • The critical is the political in philosophy: it shows the incommensurability of phrase families (Kant’s faculties) but it also creates passages from one to the other • The Critique of Political Reason (the 4th Critique, which was not written) is to be found in the 3rd Critique + many later essays Kant’s problem in the Critique of Judgment, the Introduction: (II) ‘a gulf (Kluft, also: abyss) between the domain of the concept of nature, as the sensible, and the domain of the concept of freedom, as the supersensible’; ‘no transition (Übergang: also: passage) possible’, ‘as if (…) different worlds’; ‘yet the latter should have an influence on the former’ (IX) ‘the great chasm (Kluft) that separates the supersensible from the appearances’; ‘to throw a bridge from one domain to the other’ Enthusiasm 2 Passages analyzed by Lyotard: 1. Between Ideas of reason (argumentative-dialectical phrases) and intuition (descriptive phrases): the symbol, indirect presentation, analogy between the ‘rules of reflection’; thus ‘the beautiful is the symbol of the morally good’ (CoJ, § 59) 2. Between understanding and practical reason: the law of nature as a type of the law of freedom (Critique of Practical Reason, A123) 3. • • • Enthusiasm: In the third Critique: a modality of the sublime: affect connected to ideas In The Conflict of the Faculties (1795): not an act of interested people (the French Revolution itself), but a feeling among the German spectators, disinterested or even against their interest (=> aesthetics, the sublime), showing a susceptibility for Ideas: not a fact (sensible intuition), but a sign of history, not proving, but indicating that humanity is capable of progress in an ethical culture = a passage from nature (the pathological aspect of feeling) to freedom (moral Ideas) In critical thought there can be no philosophy of history (Hegel, Marx), because the latter has the illusion that signs are examples or schema’s (direct presentations) Enthusiasm 3 Kant mentions other sublime feelings besides enthusiasm, such as sorrow, if grounded in moral Ideas Lyotard in The differend: (in stead of enthusiasm) the sorrow of the spectators at the end of the 20th century: if this is a sign of history, it indicates that humanity has an ear for the aggravated gap between observable historical-political reality and moral Ideas Lyotard’s own symbol: the archipelago: • Kant’s domains or faculties, Lyotard’s phrase families (science, ethics, art, dialectics, etc.), are islands separated by the sea, there are no dams connecting the islands • The faculty of judgment is a ship that takes care of the passages (war or commerce, admiral or outfitter), it has no islands of its own, but delimits the legitimacy of each island, after each movement of the ship the sea restores itself Postmodernity: not only the distance between Idea and sensible presentation (‘reality’), but also the split between finalities (between the islands: each island has its own goal) = the split of the subject and the split of reason • There is no longer a ground for assuming a unity of nature, history, and human freedom • A philosophy of phrases is better adapted to this situation than a philosophy of faculties of the subject The differend 1 • Preface: Kant’s 3rd Critique, Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations: epilogues to modernity, prologues to an honorable postmodernity; lay the ground for the thought of dispersion • • 1. 2. Here: genres of discourse (in stead of phrase families) Two types of conflicts: within a genre: litigation between genres: differend – there is no universal genre, there are no ‘meta’ rules above the genres to solve this conflict; one becomes a victim, suffering a wrong = the loss of the means to argue, when the conflict is treated in the idiom of the other genre A genre (e.g. science) defines the rules for linking – different kinds of – phrases (in science: signifying, naming, showing, and judging that the referents of the former three phrases are identical) according to a finality, a goal (in science: establishing that a referent is real) There is always the possibility that a next phrase does not fit in the same genre, that there is a leap toward another genre – politics is the multiplicity of genres, and therefore the threat of the differend on the occasion of each linking – deliberative politics is an arrangement of different genres (ethics: what ought we to be? science: what can we do? rhetoric etc.) The differend 2 Marxism (if not seen as a philosophy of history but) as a feeling of the differend – the wrong done by capital to all other kinds of phrases – has not come to an end • Capital = the economic genre = linking two phrases which presuppose each other, with the goal of reducing the loss of countable time between the event of these two phrases: the economic genre has a finality different from the finality of work – creating things But Marx understands this feeling (and the accompanying Idea of communism) as emanating from a class, a subject that wants itself; this is only possible within the (Hegelian) speculative genre The proletariat can only be the object of an Idea, whereas the real working people are referents of cognitive phrases; in order to hide this heterogeneity the party will assume a centralist organization, a monopoly over the cognitive phrases establishing the historical-political reality Budapest 1956 etc. refutes the doctrine of historical materialism: workers against the party All of this, the heterogeneity of the genres, the archipelago, is still ‘postmodern Kant’ However, in The differend the phrase is also something that happens: an event, a presentation • That a phrase happens (quod) is to be distinguished from the situation it presents (quid); the event as such is not in chronological time; the event (the quod) is forgotten as soon as one conserves it in time, representing what it presented (the quid) • Lyotard refers to the Ereignis, Heidegger’s term for event Lyotard’s second big question: his criticism of technology, ‘rules’ etc. is based on this acknowledgement of the event, before the heterogeneity of genres (linking phrases) can appear: a postmodernity ‘before’ Kant Aesthetics ‘The Sublime and the Avant-garde’ (in The inhuman) • Barnett Newman: painting Vir Heroicus Sublimis (1951), essay The Sublime is Now (1948) • Lyotard now bases the sublime on the event: terror, the threat of nothingness in Burke, the Ereignis in Heidegger; the question of time, as it ‘does not form part of Kant’s problematic’ The inhuman (1988), two types of the inhuman: A. The system: technology, development against entropy, making a totality more complex and more flexible by inventing and introducing mediating entities, repetition of the same, lexis, rules, mind (animus), representation, communication, consensus B. Childhood (infantia: no articulate speech – persists as a stowaway in the adult person), phonè, aisthèsis, birth and death, (unconscious) affect, soul (anima), matter ‘Anima minima’ (1993) • Lyotard’s criticism of aestheticism: the embellished system, beautiful but empty forms, in order to forget fate, suffering, finitude, and the body; but aisthèsis receives matter before form (Kant: matter ~ the agreeable; beauty constituted by form, the sublime is form not coming about) • Anima, not as a substance but as existing only when it is awakened out of nothingness, anesthesia; minima: awakened case by case; the work of art as an alarm for nothingness: ‘art puts death’s insignia on the sensible’ Lyotard’s third big question: art as a response to aisthèsis (sensibility), which has its tension with nothingness within sensibility itself