Analyse économique de l*intermédiation * Application au transport

advertisement

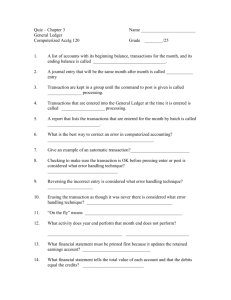

Economic Analysis of Intermediation Applied to Road Transport Maurice Bernadet IRU - 21 February 2014 1 • While there are intermediaries in all sectors of economic activity, economic theory has focused solely on intermediation in finance. There are also some studies - more applied than theoretical, however - devoted to trade intermediaries. To my knowledge, no specific work has been devoted to the logic of intermediation and the role of intermediaries in the field of transport in general, and road transport in particular. • However, we can use the concepts and analysis of the so-called “New-Institutional Economics” in an attempt to understand this logic and this role. • We shall present an extremely simplified overview of neoinstitutional analysis, although this is a very broad approach, whose scope does not specifically address intermediation issues. 2 Presentation Outline 1. New Institutional Economics 2. Transaction Costs 3. Integration vs. Outsourcing in the Transport Sector 3 Part I New Institutional Economics 4 New Institutional Economics • New Institutional Economics are linked to two extremely famous economists, as both of them received the Nobel Prize. • The first is Ronald Coase, a British economist, but who spent most of his career in the USA. In 1991 he was awarded the Nobel Prize "for his discovery and clarification of the significance of transaction costs and property rights for the institutional structure and functioning of the economy". • In 1937 he wrote The Nature of the Firm, the founding article for New Institutional Economics. 5 New Institutional Economics • The second author whose work we shall refer to is Oliver Williamson. This American economist born in 1932 received the Nobel Prize in economics in 2009. • Williamson developed the concept of transaction costs, rooted in Coase’s 1937 article, and turned it into an essential tool for analysis of market economy. • Both authors have in common a closeness to the legal dimension of economic operations. Institutions (hence the “neo-institutional” approach) and contracts are at the heart of their analysis. 6 New Institutional Economics • Both authors are particularly interested in the way in which activities by economic actors are coordinated. They schematically distinguish two methods of coordination: - by grouping activities within an institution – the company – which operates according to a hierarchical rule and is based on the principle of authority; - by coordination in the market, which operates in a decentralised way through contractual procedures and the price mechanism. • Both these forms of coordination are alternate as well as complementary and may be combined in a host of different ways (networks, franchises, subsidiarising, etc., which are “hybrid” forms). 7 New Institutional Economics • But coordination always has a cost - whether this is the cost of coordination within companies (part of the structural costs), or the transaction cost when relationships are decentralised and organised by the market. • The authors hypothesise that economic actors seek to minimise the sum of production costs and coordination costs, and that the chosen solution, in every circumstance, is that which they consider (rightly or wrongly!) the least expensive. • We see that this analysis is essential to shed light on the company’s choice between performing the activity in-house or outsourcing it to a third party via a contract. 8 New Institutional Economics • When applied to the field of transport, analysis of coordination and transaction costs serves to understand why a manufacturer or retailer might choose to perform transport on own account or, rather, to externalise the transport function. • And if the company decides to outsource the transport function, analysis of coordination and transaction costs then explains the choice between - selecting carriers (and more generally, all providers involved in the transport chain) itself and contracting with each of these, or - resorting to an intermediary to entrust this responsibility to the latter. 9 Part II Transaction Costs 10 Transaction Costs • Indeed, Coase and Williamson’s essential contribution is to state that choosing the market as a coordination tool has a cost, which “classical” theory, which supposes that competition is pure and perfect, denies. • “In order to carry out a market transaction it is necessary to discover who it is that one wishes to deal with, to inform people that one wishes to deal and on what terms, to conduct negotiations leading up to a bargain, to draw up the contract, to undertake the inspection needed to make sure that the terms of the contract are being observed, and so on.” (RH Coase, 'The Problem of Social Cost’, Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 3 (Oct., 1960), pp. 1-44) 11 Transaction Costs • The theory of transaction costs - specifically Ronald Coase gathers these into three subsets: - Costs prior to the conclusion of the contract (“search and information costs”): the costs incurred in identifying potential partners and comparing the services, prices, reliability, security, etc., which they offer; - Costs related to establishment of the contract (“bargaining and decision costs”) incurred in discussions with potential partners, cost of drawing up the contract ...; - Costs related to contract execution (“policing and enforcement costs”) incurred in monitoring service performance, service quality, accuracy of billing, etc.. 12 Transaction Costs • However, Oliver Williamson and other more recent authors complement this analysis by building an actual economic theory of contracts and seeking to identify the factors which determine the level of transaction costs. In a nutshell, we may list three factors explaining the level of transaction costs: - uncertainty and the resulting risk of opportunism; - the more or less specific nature of assets involved in the transaction; - the frequency of transactions. 13 Transaction Costs • The "real" world is very different from the theoretical world where perfect competition prevails, in that information is always costly and uncertainty is always there. • Economic agents may be rational, but their rationality is limited as their calculations are based on incomplete information. • Under these conditions the contracts themselves, even if carefully prepared, are necessarily incomplete because they cannot anticipate all contingencies that may occur. 14 Transaction Costs • Incomplete contracts open up room to maneuvre: the parties to the contract may take advantage of circumstances not covered by the contract to benefit ("opportunism") at the expense of the other party. • Incomplete contracts and the ensuing risk of opportunistic behaviour by the other party make it imperative to include enforcement measures, incentives and sanctions, arbitration and renegotiation systems in the contract in case of dispute. All such provisions are expensive to plan and implement. 15 Transaction Costs • The relative position of the parties to a contract varies greatly depending on whether the assets involved are "specific" or commonplace. • The concept of specificity is a complex one. In a somewhat simplistic view, an asset is specific if it is specialised, i.e. can only be used for the production of a particular service and hardly be redeployed – i.e. assigned to another use -, either due to this very specialisation, or for lack of a market opportunity. To illustrate the concept of specificity, let’s say that an articulated vehicle for "general cargo" is commonplace, while a car carrier vehicle is specific ... 16 Transaction Costs • The owner of a specific asset who engages in a transaction (and especially the contracting party who has to invest into a specific asset in order to engage in a transaction) can encounter two opposite situations: - the specificity of the asset does not allow another assignment, making the asset holder dependent on the other party; - it would be difficult for the other party to find another partner holding this specific asset and able to deliver, so the other party is dependent on the asset holder, and the owner of the specific asset is in a strong position. 17 Transaction Costs • The balance between these two situations is difficult and calls for particular care in drawing up the contract and monitoring its enforcement. • Note that the assets involved, whether specific or not, are not necessarily physical assets. They may be intangible assets, including the competence of the people involved in providing the service. • According to Williamson, the higher the asset specificity, the more the chosen solution will tend towards vertical integration of activities, rather than opting for a decentralised contractual mode, which is too costly and too risky. 18 Transaction Costs • The situation of contracting parties is also very different depending on whether one is dealing with a one-off transaction or frequent transactions. But here again conflicting considerations come into play: - When the transaction is infrequent, the search costs for a provider are proportionately high, the risk of choosing a "bad" partner is great, but the consequences of such a choice are limited. - When the transaction is frequent, the uncertainty associated with a service spread out over time is large, and the stakes of the choice of partner are high; contractual arrangements must take this into account and call for particular caution. 19 Transaction Costs • It is generally accepted that the higher the frequency of transactions, the more the chosen solution will tend toward integration of activities rather than outsourcing. • Furthermore, the two factors "asset specificity" and "frequency of transactions" reinforce one another: if a company needs a very specific asset for frequent use, it will be in its interest to buy the asset and provide the service itself, rather than resorting to an external provider on which it would be overly dependent. 20 Transaction Costs • In short, the pro-integration factors are: - the degree of uncertainty and related risks of opportunism, - asset specificity, - transaction frequency. • This analysis has been applied to businesses and industry more rarely to the service sector, and even more rarely to the transport sector. • However, one may give a few examples to illustrate the benefits of this analysis. 21 Part III Integration vs. Outsourcing in the Transport Sector 22 Integration vs. Outsourcing in the Transport Sector • The first work we may mention that applies New Institutional Economics to the transport sector is the thesis by Lionel Grand ("Les relations de sous-traitance dans le secteur des transports routiers de marchandises" - Lyon, 1997). • The purpose of the thesis is to analyse subcontracting in road haulage, especially the phenomenon of subcontractor dependence on their principals (forwarding agents and other carriers) depending on the specificity (or commonness) of the (tangible or intangible) assets involved and the frequency of transactions. • This thesis leads to a typology of subcontracting relationships. 23 Integration vs. Outsourcing in the Transport Sector • More recently a paper by Emeric Lendjel and Marianne Fischman (to be published) analysing how container transport is organised on the Rhone, shows how complex this organisation is. Performing this service involves a huge number of transactions: - A "mother" transaction whereby a carrier takes responsibility for the operation - "Secondary" transactions: hiring a container, hiring space on a barge, loading the container onto the barge, driving the barge, unloading the container, etc.. , not to mention pre- and postcarriage operations. • According to the authors, performing this service involves at least 8 transactions or sub-transactions. 24 Integration vs. Outsourcing in the Transport Sector • Now the analysis conducted by the authors shows that governance structures put in place by both operators involved in this market are integrated or quasi-integrated (services performed in-house, or outsourced to external providers, but which are subsidiaries or companies in which they hold minority interests). • This article has the merit of emphasising an original feature of transport services: while the transport chain may occasionally be simple and involve only a single transaction, it is common for the chain to be made up of successive segments involving several physical or administrative - services which must be coordinated, especially when the transport operation is multimodal and / or international. 25 Integration vs. Outsourcing in the Transport Sector • Does neo-institutional analysis serve to explain the distribution of transport between own-account and for hire or reward? • The answer is not straightforward: -the tendency to internalise (own-account transport) is unquestionably stronger when the services to be performed are frequent and involve specialised assets (physical or knowhow); -yet own-account transport may occur even when these conditions are not met. Manufacturers and retailers, in particular, may perform own-account transport which does not rely on specific assets. 26 Integration vs. Outsourcing in the Transport Sector • In very broad terms, studies show that the production cost of own-account transport is often much higher than that of transport for hire or reward (especially because the rate of use of the vehicle is low, driver salaries are higher...). • The existence of transaction costs when outsourcing can partially offset this cost difference – however, only in part. And besides, these costs are generally ignored or underestimated by manufacturers or retailers. • Therefore, the assumption by neo-institutional theory that companies seek to minimise the sum of production and coordination costs does not appear to be verified. 27 Integration vs. Outsourcing in the Transport Sector • If the share of own account transport is greater than predicted by theory, one may invoke four arguments related to the behaviour of manufacturers and retailers: - their choices are based on incomplete information, particularly regarding the cost of own account, which they tend to underestimate - their rationality is thus limited; - they want to control service provision directly for the sake of quality; - performing own account transport allows them to keep in touch with clients – the driver is a "sales representative" of the company; - they wish to retain a “test” activity allowing them to make comparisons with transport for hire or reward which they otherwise use. 28 Integration vs. Outsourcing in the Transport Sector • Ultimately, the neo-institutionalist approach, because it neglects these arguments, does not provide a complete analysis of the conditions of the choice between integration and outsourcing. • These arguments - or at least a part of them - are specific to the transport sector. • But suppose a manufacturer or retailer decides to outsource transport services. Does the neo-institutionalist theory serve to understand the choice between - internalising the choice of carriers and other service providers, or - outsourcing this choice and resorting to an intermediary? 29 Integration vs. Outsourcing in the Transport Sector • If the company wishes to select the transport providers itself, it must: - analyse this service to break it down into its various physical and administrative segments, - estimate the uncertainty attached to performance of these different segments and assess related risks, - gather information to identify the operators able to perform these segments and find out what they offer, at what price, with what quality assurance ... - draw up with each provider a contract stipulating, among other things, how their services will interact with those of other operators upstream and downstream, - monitor performance of the various services, - etc.. 30 Integration vs. Outsourcing in the Transport Sector • In other words, the company must hold or acquire knowledge and skills which, according to New Institutional Economics, constitute a specific asset. This intangible asset is undoubtedly costly. • Acquiring such an asset is only possible if transactions are frequent in order to make the investment profitable. • And even if the company has this competence, transaction costs in dealing with a large number of operators can be very high if the service is a complex one. • Therefore, in practice, except in the case of relatively simple and repetitive services, it is in the interest of the manufacturer or retailer – the “loader” - to outsource the organisation of the service. 31 Integration vs. Outsourcing in the Transport Sector • Instead of multiple contracts with operators, the loader concludes a single contract with an intermediary - a transport organiser - who has the competence - the knowledge and know-how - to select operators, assess risks, draw up contracts, monitor implementation, etc.. • For the loader, transaction costs are limited to the search for and drawing up of a single contract. In addition, a commission must be paid. However, the commission amount is less than the transaction costs the loader would have to bear if it did not outsource the choice of operators involved in the transport chain. 32 As a conclusion • New Institutional Economics are primarily concerned with the forms of coordination of economic actors, which it schematically describes by opposing integration within a company, to market coordination through contractual arrangements. Relating to the latter, it identifies and highlights the role of transaction costs. • The analysis of transaction costs serves to explain, or at least to shed light on, the choice which companies have between integration or outsourcing. 33 As a conclusion • This analysis is particularly relevant when considering the role of intermediaries: intermediation appears as a means to: - pass on to the intermediary the transaction costs which would be involved in selecting several co-contractors, - restrict transaction costs - for the company outsourcing service production – to those of establishing a single contract with the intermediary. 34 Thank you. 35