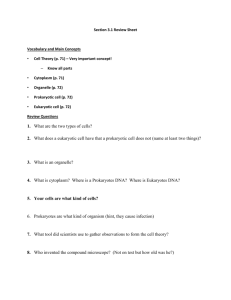

Ch. 27 & 28 Notes

advertisement

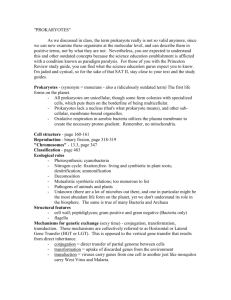

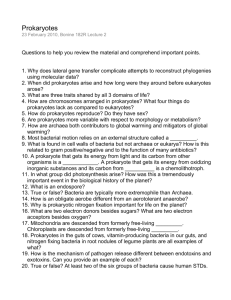

Chapter 27 & 28 Prokaryotes & Protists Ch. 27 ~ Prokaryotes Overview: They’re (Almost) Everywhere! Most prokaryotes are microscopic But what they lack in size they more than make up for in numbers The number of prokaryotes in a single handful of fertile soil Is greater than the number of people who have ever lived Prokaryotes thrive almost everywhere Including places too acidic, too salty, too cold, or too hot for most other organisms Figure 27.1 27.1 ~ Structural, functional, and genetic adaptations contribute to prokaryotic success Most prokaryotes are unicellular Although some species form colonies Prokaryotic cells have a variety of shapes The three most common of which are spheres (cocci), rods (bacilli), and spirals 1 m (a) Spherical (cocci) 2 m (b) Rod-shaped (bacilli) 5 m (c) Spiral Cell-Surface Structures One of the most important features of nearly all prokaryotic cells Is their cell wall, which maintains cell shape, provides physical protection, and prevents the cell from bursting in a hypotonic environment Using a technique called the Gram stain Scientists can classify many bacterial species into two groups based on cell wall composition, Gram-positive and Gram-negative Lipopolysaccharide Cell wall Peptidoglycan layer Cell wall Outer membrane Peptidoglycan layer Plasma membrane Plasma membrane Protein Protein Grampositive bacteria Gramnegative bacteria 20 m (a) Gram-positive. Gram-positive bacteria have a cell wall with a large amount of peptidoglycan that traps the violet dye in the cytoplasm. The alcohol rinse does not remove the violet dye, which masks the added red dye. Figure 27.3a, b (b) Gram-negative. Gram-negative bacteria have less peptidoglycan, and it is located in a layer between the plasma membrane and an outer membrane. The violet dye is easily rinsed from the cytoplasm, and the cell appears pink or red after the red dye is added. The cell wall of many prokaryotes Is covered by a capsule, a sticky layer of polysaccharide or protein 200 nm Capsule Figure 27.4 Some prokaryotes have fimbriae and pili Which allow them to stick to their substrate or other individuals in a colony Fimbriae 200 nm Figure 27.5 Motility Most motile bacteria propel themselves by flagella Which are structurally and functionally different from eukaryotic flagella Flagellum Filament 50 nm Cell wall Hook Basal apparatus Figure 27.6 Plasma membrane Internal and Genomic Organization Prokaryotic cells Usually lack complex compartmentalization Some prokaryotes Do have specialized membranes that perform metabolic functions 0.2 m 1 m Respiratory membrane Thylakoid membranes Figure 27.7a, b (a) Aerobic prokaryote (b) Photosynthetic prokaryote The typical prokaryotic genome Is a ring of DNA that is not surrounded by a membrane and that is located in a nucleoid region Chromosome Figure 27.8 1 m Some species of bacteria Also have smaller rings of DNA called plasmids Draw a prokaryotic cell and label the DNA and plasmids Prokaryotes reproduce quickly by binary fission And can divide every 1–3 hours Many prokaryotes form endospores Which can remain viable in harsh conditions for centuries Endos pore Figure 27.9 0.3 m 27.2 A great diversity of nutritional and metabolic adaptations have evolved in prokaryotes Examples of all four models of nutrition are found among prokaryotes: List Energy source & Carbon source: Photoautotrophy Chemoautotrophy Photoheterotrophy Chemoheterotrophy Major nutritional modes in prokaryotes Table 27.1 27.3 Molecular systematics is illuminating prokaryotic phylogeny Until the late 20th century Systematists based prokaryotic taxonomy on phenotypic criteria Applying molecular systematics to the investigation of prokaryotic phylogeny Has produced dramatic results A tentative phylogeny of some of the major taxa of prokaryotes based on molecular systematics Domain Archaea Domain Bacteria Proteobacteria Figure 27.12 Universal ancestor Domain Eukarya Bacteria Diverse nutritional types Are scattered among the major groups of bacteria The two largest groups are The proteobacteria and the Gram-positive bacteria 2.5 m Chlamydias, spirochetes, Gram-positive bacteria, and cyanobacteria 5 m Chlamydia (arrows) inside an animal cell (colorized TEM) 1 m 5 m Leptospira, a spirochete (colorized TEM) Hundreds of mycoplasmas Streptomyces, the source of covering a human fibroblast cell many antibiotics (colorized SEM) (colorized SEM) 50 m Figure 27.13 Two species of Oscillatoria, filamentous cyanobacteria (LM) Archaea Archaea share certain traits with bacteria And other traits with eukaryotes Table 27.2 Some archaea live in extreme environments Extreme thermophiles thrive in very hot environments Extreme halophiles live in high saline environments Colorful “salt-loving” archae live in these ponds near San Fransisco. Used for commercial salt production. Methanogens Live in swamps and marshes and produce methane as a waste product 27.4 Prokaryotes play crucial roles in the biosphere Chemical Recycling Prokaryotes play a major role in the continual recycling of chemical elements between the living and nonliving components of the environment in ecosystems Chemoheterotrophic prokaryotes function as decomposers Breaking down corpses, dead vegetation, and waste products Nitrogen-fixing prokaryotes Add usable nitrogen to the environment Symbiotic Relationships Many prokaryotes Live with other organisms in symbiotic relationships such as mutualism and commensalism Figure 27.15 27.5 Prokaryotes have both harmful and beneficial impacts on humans Some prokaryotes are human pathogens But many others have positive interactions with humans Prokaryotes cause about half of all human diseases Lyme disease is an example Figure 27.16 5 µm Prokaryotes in Research and Technology Experiments using prokaryotes have led to important advances in DNA technology Prokaryotes are the principal agents in bioremediation The use of organisms to remove pollutants from the environment Prokaryotes are also major tools in Mining, the synthesis of vitamins, production of antibiotics, hormones, and other products Ch. 28 ~ Protists 28.1: Protists are an extremely diverse assortment of eukaryotes Protists are more diverse than all other eukaryotes And are no longer classified in a single kingdom Most protists are unicellular, colonial or multicellular Protists, the most nutritionally diverse of all eukaryotes, include Photoautotrophs, which contain chloroplasts Heterotrophs, which absorb organic molecules or ingest larger food particles Mixotrophs, which combine photosynthesis and heterotrophic nutrition There is now considerable evidence that much of protist diversity has its origins in endosymbiosis Cladogram of Protists: 28.3: Euglenozoans have flagella with a unique internal structure Euglenozoa is a diverse clade that includes Predatory heterotrophs, photosynthetic autotrophs, and pathogenic parasites Dinoflagellates Are a diverse group of aquatic photoautotrophs and heterotrophs Are abundant components of both marine and freshwater phytoplankton Ciliates, a large varied group of protists Are named for their use of cilia to move and feed Have large macronuclei and small micronuclei Conjugation – Two cells exchange haploid micronuclei (similar to prokaryotic conjugation). **Produces genetic variation 28.5 Hairy and smooth flagella 1. Diatom – Surrounded by a two part glass like wall and are a major component of phytoplankton. Phytoplankton account for half of the photosynthetic activity on earth – responsible for much of the oxygen in our atmosphere. 2. Golden Algae – Have two flagella and their color results from carotenoids. 3. Brown Algae – multicellular mostly marine protists, commercially used; seaweeds 28.6 Threadlike pseudopodia Pseudopodia extend and help to injest microorganisms. 28.7 ~ Amoebozoans Lobed shaped pseudopodia *Entamoebas – parasites of vertebrates and cause amebic dysentry in humans. *Slime molds – extend their pseudopodia through decomposing material, engulfing food by phagocytosis. 28.8 ~ Red & Green Algae are the closest relatives of land plants.