History of Inmate Fees - The Real Cost of Prisons Project

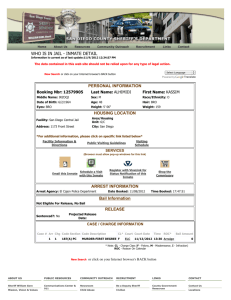

advertisement