Autism-mentoring project

advertisement

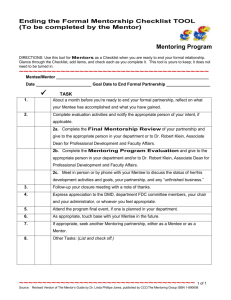

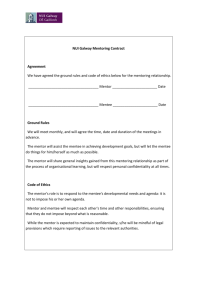

10 – 10.30 10.30 - 11 Introduction to the project (aims of the day, objectives, intro to mentoring) Autism in an historical and social context 11 - 11.15 Tea break 11.15 – 11.45 11.45 – 12.15 A different way of thinking Sensory perceptions and autism 12.15 - 1 Lunch 1 – 1.30 1.30 – 2 Interaction and communication Stress and anxiety 2 – 2.15 Tea break 2.15 – 2.45 2.45 – 3.15 Autism and gender The SPELL framework 3.15 – 3.30 Tea break 3.30 – 4 4 – 4.30 4.30 – 5 Boundaries and recording, risks and safeguarding The Personal Wellbeing Index (PWI), goalsetting and Personal Construct Theory Concluding guidance for project A two-year pilot study to: Establish a mentoring scheme designed with input from people on the autism spectrum; Evaluate its effectiveness in improving the wellbeing of young adults on the autism spectrum aged 16-24. The National Audit Office’s (2009)* report Supporting People with Autism through Adulthood highlighted the dearth of services for adults on the spectrum. At the 2007 forum ‘Successful Futures for Adults with Autism’ many said that they would benefit from oneone, time-limited, goal-oriented support, akin to life coaching or mentoring. Specialist mentoring schemes for people on the autism spectrum are rare. *National Audit Office (2009) Supporting People with Autism through Adulthood. Available at: http://www.nao.org.uk/report/supportingpeople-with-autism-through-adulthood/ An advisory board has input into the design of this training for mentors of people on the autism spectrum. A minimum of 12 mentors will receive this training and be matched with mentees. Mentees and mentors will collaboratively come up with goals for mentoring. Mentoring will take place for six months. Various measures will be used to assess its effectiveness and gain the views of mentees and mentors on their experiences of participating in the programme. Lead researcher: Dr Nicola Martin Research assistants: Damian Milton Tara Sims What do you hope to gain from today? Our objectives include: Providing you with information on autism, both from a theoretical perspective and from the viewpoint of people on the autism spectrum. Developing an understanding of the role of a mentor and the specific approaches and skills involved. Guiding you in how the project will run and the accompanying documentation. Mentoring and Befriending Foundation (2014): A time-limited goal-orientated relationship Supports both personal and vocational learning and development. An experienced person providing guidance and support to another less experienced person. A voluntarily relationship in which goals and outcomes are directed by the mentee. Helping with goal-setting and action – prioritisation and time-management Helping with change and transition Helping with challenges in social and personal interactions Developing self-confidence; Providing support in getting to know new environments or procedures Offering advice and guidance Helping explore options for the future Giving (and receiving) constructive feedback. Split into groups of three. Each group to take one of the following: Counselling, Advocacy, Coaching and Befriending Decide as a group: A definition; In what ways it is similar to mentoring; In what ways it is different to mentoring. Feedback to the larger group. Counselling Advocacy Coaching Befriending We will match you with a mentee – we will do this based on: What they hope to gain from mentoring and how well this matches with your experience. The type of mentoring they would like (face-face, telephone, online etc.) and what you are able to offer. We will arrange a convenient time for your first meeting with your mentee A member of the research team will also attend this meeting in order to You will then meet once per week with your mentee for one hour. Use the goals set and Salmon Line to help plan smaller goals and monitor progress; Jointly complete the meeting record sheet during/after each session; Individually complete the reflective journal after each session. You can contact the research assistants at any point during the six months of the mentoring, if you have any questions, require advice or guidance or are concerned about anything that is discussed in the meetings. You will be invited to attend a peer supervision session with other mentors approximately 3 months into the mentoring. Complete the Salmon Line exercise again to review the progress that has been made towards your mentee’s goals. After the last mentoring session, you will meet with the research assistants to complete another PWI form, participate in an interview and give in completed goal setting sheets, meeting record sheets and reflective journals. McGowan B (2007) Practice Briefing Paper No 11: Towards an Understanding of Mentoring, Social Mentoring and Befriending. Brighton University: CUPP/EQUAL/University of Brighton Social Mentoring Research Group Participatory Action Research Programme EQUAL Brighton and Hove. Miller A (2002) Mentoring students and young people. Norfolk, UK: Routledge. The Mentoring and Befriending Foundation (2014) What is Mentoring? Retrieved 26/08/14; available at: http://www.mandbf.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/What-ismentoring-and-befriending-5.8.14.pdf Western S (2012) Coaching and Mentoring: A Critical Text. London, UK: Sage. Damian E M Milton, London South Bank University (2015) Write down what you think autism is – or what you have heard autism is from other sources, such as the media. We will then gather feedback and discuss. Origins of the term – Bleuler, Kanner and Asperger. How was ‘autism’ defined before it was called ‘autism’? Changing psychiatric lens – Bettleheim, Rimland and Wing and Gould. Parent activism and charities. The neurodiversity movement and autistic selfadvocacy. What is autism? A contested terrain. Psychoanalysis Behaviourism Cognitivism and Neuroscience Sociology and Critical Disability Studies Autism from the ‘inside-out’ (Williams, 1996) Models of disability: Medical: disability as something abnormal and pathological to be treated. Social: split between social barriers of disability and physical/mental ‘impairment’. Bio-psycho-social: taking into account biological, psychological and social aspects of disability. Some theorists also question the assumptions of ‘impairment’ and ‘normalcy’ (see Milton, 2012). ‘Extremes of any combination come to be seen as 'psychiatric deviance'. In the argument presented here, where disorder begins is entirely down to social convention, and where one decides to draw the line across the spectrum.’ (Milton, 1999 - spectrum referring to the 'human spectrum of dispositional diversity'). Impairment, deficit and the ‘spiky profile’. Embodied, dispositional, neurological...diversity! Prevalence rates and changing diagnostic criteria. Rates of diagnosis and the gender divide. Essential differences or social expectations? Passing, masking, and psycho-emotional disablism (Milton and Lyte, 2012). Asperger Square 8 blogsite (2014): http://4.bp.blogspot.com/_1vPB2M2IMiI/SucK5Gau3TI/AA AAAAAACeQ/X8ANAC-forQ/s1600-h/social.model.png Milton, D. (1999) The Rise of Psychopharmacology [Masters Essay – unpublished]. University of London. Milton, D. and Lyte (2012) The normalisation agenda and the psycho-emotional disablement of autistic people, Autonomy: the Journal of Critical Interdisciplinary Autism Studies. Vol. 1(1). Accessed from: http://www.larryarnold.net/Autonomy/index.php/autonomy/article/view/9. Williams, D. (1996) Autism: An Inside-Out Approach. London: Jessica Kingsley. Damian E M Milton – London South Bank University (2015) Refers to the ability to maintain an appropriate problem-solving strategy in order to attain a future goal. Yet – there may be a difference within the way autistic executive processing operates, rather than an impairment or deficiency? Refers to problems with processing overall contextual meanings, whilst simultaneously having advantages in processing details or parts of an overall context. Yet – many autistic people are able to process gist meaning and whole pictures. Please read the handout regarding the ‘interest model’ of autism. You will be shown a clip from the film ‘My Autism and Me’ – this will be followed by an open discussion about the clip. Set mentoring scenario activity about multitasking and/or vagueness and gist thinking? An exercise in empathy Why might Paul be doing this? How can you find out why Paul might be doing this? How might you help as a mentor? How will you know if you are helping? Paul is working on his computer on a history project which is part of his A level course work. He is spending a vast amount of time on a small detail of this project which is worth 10% of one exam. He is taking four subjects. Paul needs 4 (grade A or B) A levels to get into his chosen university. Damian E M Milton – London South Bank University (2015) Sensory integration and fragmentation. Hypo and hyper sensitivity. Context and motivation. Stressful stimuli. Stress, arousal and sensory overload – ‘meltdown’ and ‘shutdown’. Synesthesia. “Aren’t all autistic people visual thinkers?”. Pattern thinking and Hyperlexia. Monotropism and the ‘attention spotlight’. The block design and embedded figure tests. ‘Non-verbal’ intelligence tests (Dawson et al., 2007) How many senses does someone have? What would ‘hyper’ and ‘hypo’ sensitivity in these senses be like? What may help someone with such sensitivities? Brief explanation – followed by a mentoring scenario activity (a cluttered noisy poorly-lit environment at a meeting?). An exercise in empathy Why might Jean be doing this? How can you find out why Jean might be doing this? How might you help as a mentor? How will you know if you are helping? Jean has recently started a clerical job in an open plan office which is hot, noisy, crowded and has strip lighting. Her bus was late, she stood up all the way and arrived late. Her supervisor said ‘what time do you call this’ . Jean looked flustered and the supervisior said ‘nevermind-just finish that stuff off from Friday chop chop’. Jean went to the toilet and locked herself in. Fifteen minutes later she was still there. Dawson, M., Soulieres, I., Gernsbacher, M., and Mottron, L. (2007) ‘The Level and Nature of Autistic Intelligence’. Psychological Science. Vol. 18(8): 657-662. Damian E M Milton – London South Bank University (2015) The ability to empathise with others and imagine their thoughts and feelings, in order to comprehend and predict the behaviour of others (also called ‘mindreading’ and ‘mentalising’). A case of mutual incomprehension? Rather than seeing the breakdown in interaction between autistic and non-autistic people as solely located in the mind of the autistic person. The theory of the double empathy problem sees it as largely due to the differing perspectives of those attempting to interact with one another. Add in stuff from communication section... Damian E M Milton – London South Bank University (2015) An exploration of factors that influence the levels of stress experienced by autistic people, and how this can produce a negative worsening cycle. How continuing high levels of stress and alienation can lead to mental ill-health. Finally concluding by looking at what can be done to reverse the negative spiral of stress that can blight the lives of autistic people. As with the rest of the population – great deal of diversity in personality and temperament. Often with differing responses to stressful experiences when encountered. The ‘fight or flight’ response – ‘meltdowns’ and ‘shutdowns’. The ‘meltdown’ response and misunderstandings of it. ‘Challenging behaviour’. No choice in the matter. Non-autistic people meltdown too – e.g. road rage. Noticing the less obvious such as more passive natured autistic people and the 'shutdown' response. Characterised by withdrawal. Often unable to think clearly or to express oneself at all. Again – no choice in the matter. Shutdowns that are infused with emotional content and/or confusion can lead to a panic attack response. This can be characterised by hyperventilating, and in a worst case scenario – passing out unconscious. Once in such an overloaded state, confusion reigns and communication becomes largely impossible. Do everything you can to reduce the stress in order to help. Do not ask ‘are you alright?’ – as one blatantly is not! The ‘monotropic’ focus (Murray et al. 2005, Lawson, 2010, Milton, 2012). Multi-tasking, integrating information, and fragmentation. Interruptions to the ‘attention spot light’. “95% of people don’t understand me”. “Friends are overwhelming”. “Adults never leave me alone”. “Adults don’t stop bullying me”. Quotes taken from Jones et al. (2012). How others see you and how you see yourself. Emotional disjuncture and ‘identity crisis’. ‘Exposure anxiety’ (Williams, 1996). The denigration of difference (Tajfel and Turner, 1979). ‘In’ and ‘out’ groups, stigma and discrimination. Living with almost constant stress and social disjuncture, can be even more highly damaging when unrecognised. Alienation and isolation, withdrawal from society. Mental ill-health – from social anxiety issues to depression and catatonia. Remember – the outward manifestation of stress may be a lack of expression too. Acceptance of the autistic way of being, work with the autistic person and not against their autism. Watch out for ‘triggers’ in the environment (although sometimes these cannot be avoided – e.g. the dreaded fire alarm!). Explore interests and fascinations together. Having strong rapport and building mutually fulfilling and trusting relationships. Encourage autistic companionship. Encourage understanding of non-autistic people and culture, rather then teaching how to poorly mimic what one is not. ‘Low arousal’ is not ‘no arousal’ – many sensory experiences are fun! Jones, G., English, A., Jones, G., Lyn-Cook, L., and Wittemeyer, K. (2012) The Autism Education Trust National School Standards. Autism Education Trust. Lawson, W. (2010) The Passionate Mind: how people with autism learn. London: Jessica Kingsley. Milton, D. (2012) So what exactly is autism? Autism Education Trust. Murray, D., Lesser, M. and Lawson, W. (2005) ‘Attention, monotropism and the diagnostic criteria for autism.’ Autism. Vol. 9(2), pp. 136-156. Tajfel, H. and Turner, J. (1979) An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In D. Langbridge and S. Taylor (ed’s) Critical Readings in Social Psychology. Milton Keynes: Open University. Williams, D. (1996) Autism: An Inside-Out Approach. London: Jessica Kingsley. Mentoring scenarios involving someone having a meltdown and someone having a panic attack (perhaps for the exact same reasons – and groups swap feedback?). Jean is still in the toilet after half an hour. She is sitting on the floor, feeling hot, anxious and frightyened. She is very quiet and preoccupied and is not sure how to get herself out of the situation. Her supervisor is asking office staff where she is. Jean can hear him. Jean is still in the toilet. She is running the taps, splashing water on her face and flicking water around the room. She is saying over and over again ‘oh no, oh no, oh no’. People in the office can hear her and a colleague is banging on the door and saying ‘what’s going on in there?’ DO… Be aware of your own personal boundaries. Avoid getting into situations that could be misinterpreted. Think before you say, "Yes". Maintain focus on assisting the mentee with their goals. DON’T… Give out your home telephone number or address to your mentee. Take your mentee to your own home or meet in their home. Get involved in a relationship with you mentee that crosses professional boundaries. Give or lend your mentee money. Complete the mentoring agreement during the first meeting to agree the following: Mentoring is once per week for one hour. Always meet in a public place where you both feel comfortable - never mentor or mentee’s home. Contact between meetings only for the purposes of altering details about the next meeting. Only cancel a meeting if absolutely necessary and make sure you give your mentee as much notice as possible. Read the lone worker guidance and follow this at all times when meeting your mentee. Ensure that any information about your work as a mentor, which you share with family, friends or colleagues, is restricted to general information only. Be very careful what you talk about so that you don't reveal personal information about your mentee to anyone outside the project. Do not promise your mentee you will keep secrets – make them aware that if you believe they or someone else are at risk you will have to share the information with project staff. Speak to project staff if you have any concerns for the safety of your mentee or anyone else following something your mentee has disclosed to you. Get into pairs. Read your scenario and between you discuss the following: How you would respond according to your own personal boundaries How you would respond according to the boundaries of the mentoring relationship What you would consider in terms of: ▪ Your own personal boundaries ▪ Confidentiality ▪ Lone working Feed back to the group. Some people embrace A.S./disability identity but others don’t and consequently avoid associated services Diagnosis is necessary to access the mentoring service Adult diagnostic services and post diagnosis support are scarce 'A diagnosis would have helped so I didn't feel my lack of social skills was a deficit of mine‘. (ASPECT) ‘Having a diagnosis of AS in school means, as an adult, you feel like you can never actually participate normally in everything with everyone else‘. (Student) Mental health is a fluctuating state, dependent on various factors (Samaritans 2006). People on the autism spectrum are particularly vulnerable to mental health problems (Tantam & Prestwood 1999). It is important to feel comfortable having exploratory discussions with people who express despair or suicidal thoughts. The majority of people who express suicidal thoughts are unlikely to carry through their thoughts to action, but you must take it seriously when somebody expresses despair or suicidal ideation (Samaritans 2005). If your mentee expresses despairing thoughts or thoughts that could be described as potentially suicidal: Respond in a compassionate, proportionate and timely manner; Make sure they are aware that you may not be able to keep everything they say confidential if you are concerned for their safety or the safety of somebody else. Keep discussions brief to avoid thought getting “stuck in their head” (Cole-King et al 2012) For advice or support you (and your mentee) can contact: Local mental health crisis services: 0800 731 2864 Samaritans: 08457 909 090 If you are ever in doubt about a boundary, confidentiality or disclosure issue, speak to one of the project research assistants: Tara: simst@lsbu.ac.uk; Damian: miltond@lsbu.ac.uk Brewer AM (2011) Positive Mentoring Relationships: Nurturing Potential. In S Roffey (Ed.) Positive Relationships: Evidence Based Practice across the World. London, UK: Springer Science and Media. Cole-King A, Walton I, Gask L, Chew-Graham C and Platt S (2012) Suicide Mitigation in Primary Care. London, UK: RCGP/RCPsych Primary care Mental Health Forum. Headspace (2009) MythBuster: Suicidal Ideation. Victoria, Australia: OrygenYouth Health Research Centre. Milton, D. (2012a) ‘On the Ontological Status of Autism: the ‘Double Empathy Problem’. Disability and Society. Samaritans (2005) The Listening Wheel. Surrey, UK: The Samaritans Enterprises Limited. Samaritans (2006) Sliding Scale. Surrey, UK: The Samaritans Enterprises Limited . Tantam, D. and Prestwood, S. (1999). A mind of one's own: a guide to the special difficulties and needs of the more able person with autism or Asperger syndrome. 3rd ed. London: National Autistic Society Damian E M Milton, London South Bank University (2015) Activity: please fill out a personal wellbeing index. Then if you like you can fill out a the ‘wheel’ in the handout (instructions on the handout). In pairs, set three goals... The starting point for PCT is the idiosyncratic ways in which people make sense of the world and how this influences their actions. PCT attempts to approach issues through the viewpoint of the individual experiencing them, rather than fitting them into preconceived models. Rather than seeing any interpretation as ‘correct’, one should look pragmatically at how useful such a framing is to one’s purposes. On the lines below, please mark how satisfied you are with your current level of attainment of each of your goals for mentoring Goal 1:____________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________ 1 Completely dissatisfied 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Completely satisfied (Adapted from Salmon 1988*) The person is asked to place him/herself on the line in relation to their perceptions of how they are performing in this area currently. Ideas for progressing towards achievement can be generated in small, achievable steps. For each aspect of life that is chosen, it is represented on a continuum with one end representing satisfaction in that area and the other representing dissatisfaction. Salmon P (1988) Psychology for Teachers: An Alternative Approach. London: Routledge A mentee identifies that their goal is to have a better relationship with their parents. Ask the mentee to give their view on what the bottom end of the continuum looks like and what the top end of the continuum looks like. Ask the mentee to mark on the continuum where they are currently and what this looks like. Discuss with the mentee where they would like to be on the continuum at the end of the six months mentoring and what this would look like. Then explore participant’s beliefs about how they can move along the line from where they are now to the point they would like to be. ‘People need to get over the idea that the 'neuro typical way is the right way and any other way is wrong. The AS way is just as valid, in fact better in some respects. We should be accepted in our own right, and the emphasis should be on educating NT's not to be so discriminatory, and to get over the absurd and offensive idea that they are better than anyone else. People with AS don't need to be cured, or trained how to be 'normal'. It's the 'normal' people who need to learn that, contrary to what they think, they are not the pinnacle of God's creation and there is, in fact, a lot they could learn from Aspies. They need to be taught not to be prejudiced and discriminatory, and to accept and accommodate us for who we are’ (ASPECT) Get into pairs. One person from each pair to choose an area of their life they would like to develop in / work on (in role of mentee). Mentor to lead a discussion about what being on the bottom end of the continuum would look like and what being at the top end of the continuum would look like (what would be happening, how people would be feeling, the consequences of this etc.) Mentor to ask mentee to mark on the continuum where they are currently and explore with them what this looks like. Mentor to discuss with mentee where on the continuum they would ideally like to be and explore their beliefs about how they can move along the line from where they are now to the point they would like to be. Prompts that can be used: ▪ What are they doing/have they done in the past that allows them to be at this point in the scale (and not further towards the dissatisfied/underachievement end of the scale) – can only do this if people have not positioned themselves right at the bottom. ▪ What do they think would help them to move closer towards the desired position on the scale? Swap roles and repeat. Your pack contains the following documents for recording during mentoring: mentoring contract reflective diary sheets session recording sheets The mentoring contract will be agreed with your mentee in the first session and referred to as necessary throughout the relationship. The other two documents will be completed after each session to act as a continual record of the mentoring relationship. Complete the self-referral form, demonstrating how you meet the criteria outlined in the person specification. If you meet the criteria you will be invited to an interview with project staff. We will then try to match you with a mentee – this may not be possible (even if you meet the criteria) – in that case we will keep you on a list of “reserve mentors” and may request your participation at a later date. We will match you with a mentee – we will do this based on: What they hope to gain from mentoring and how well this matches with your experience. The type of mentoring they would like (face-face, telephone, online etc.) and what you are able to offer. To facilitate this, we require you to: Fill in a mentoring referral form Attend a 15 minute one-one discussion about the role We will arrange a convenient time for your first meeting with your mentee – a member of the research team will also attend this meeting in order to: Facilitate completing consent forms; Complete/collect your PWI forms; Facilitate Filling in the mentoring agreement form; Facilitate Goal setting using the Salmon Line; Ensure you are both confident with the paperwork that requires completing after each session; Make sure you both have the contact details of project staff; Answer any questions either of you may have; Facilitate setting future meetings. Once per week for one hour in way agreed (faceface/telephone/online) Guided by the mentee regarding what they wish to discuss or work on; Use the goals set and Salmon Line to help plan smaller goals and monitor progress; Jointly complete the meeting record sheet during/after each session – this is really important as it will tell us how often and for how long you and your mentee met; Individually complete the reflective journal after each session. You can contact the research assistants at any point during the six months of the mentoring, if you have any questions, require advice or guidance or are concerned about anything that is discussed in the meetings: simst@lsbu.ac.uk miltond@lsbu.ac.uk Peer supervision session with other mentors approximately 3 months into the mentoring – date tbc. In your last meeting with your mentee, you will complete the Salmon Line exercise again to review the progress that has been made towards your mentee’s goals – a research assistant can facilitate this session if you would like. After the last mentoring session, you will meet with the research assistants to complete another PWI form, participate in an interview and give in completed goal setting sheets, meeting record sheets and reflective journals.