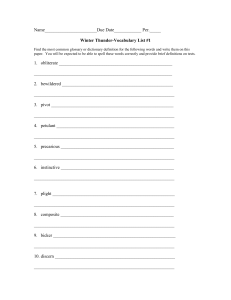

Copyright Sam Hurcom Normativity, Reason and the act of

advertisement

Copyright Sam Hurcom Normativity, Reason and the act of Promising This essay will question the extent to which our ability to reason objectively (to recognise reasons for action that are distinct from our personal/subjective desires and goals) is necessary to enact promises. This essay will note the tight relation between normative evaluation and reasoning, before assessing accounts of the historical context under which individual’s made normative choices distinct from mere instinctive willing1 and humankind first made promises. It will be argued that there have (and still can) be cases in which promises have been made without recognition of any objective (public) reasons to act and that individuals can make and keep promises purely for personal/subjective reasons. Whilst the act of promising will be scrutinised, the arguments made could stretch to other possible moral action that Kantian theorists traditionally argue requires individuals to have an awareness of objective/public reasons. In chapter nine of Self-Constitution, Korsgaard argues that the act of promising requires individuals to “deliberate together, to arrive at a shared decision”2. In turn, our ability to deliberate together requires a specific conception of reasons; public reasons. Korsgaard argues that public reasons are those “…whose normative force can extend across the boundaries between people”3. In this sense Korsgaard is likening public reasons to a more traditional understanding of objective reasons, by arguing that public reasons are those which can extend beyond the mere personal interests and desires of the subjective individual4. Private, or subjective reasons to act, are agent relative and concerned with the 1 The context in which individual’s made normative choices concerning the principles from which action can be derived rather than simply choosing means to satisfy instinctive ends 2 Christine Korsgaard, Self-Constitution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012) p.190 3 Ibid. p.191 4 I take my distinction between Objective and Subjective rationality (forms of reasoning) from the work of Max Horkheimer. “It [subjective reason] is essentially concerned with means and ends, with the adequacy of 1 Copyright Sam Hurcom fulfilment of personal goals and desires held by an individual. Likewise, public or objective reasons are agent neutral in that they motivate all individuals to act in spite of their personal desires or goals; “…a universalizability requirement commits me to the view that if I have a reason to do action-A in circumstances-C, I must be able to will that you should do action-A in circumstances-C, because your reasons are normative for me”5 Korsgaard argues that only through a public conception of reasons can we be motivated to make and enact promises to one another i.e. only through our ability to recognise reasons distinct from our personal desires and goals can we be motivated to keep promises made with one another. In short, Korsgaard suggests that only in light of a public conception of reasons will we arrive in any “moral territory”6 – only in light of a public conception of reasons will we be capable of recognising moral laws (such as the Categorical imperative) as motivating reasons for action. Is this conception of promising, - as a manifestation of our ability to recognise public reasons - necessarily true when we focus upon the historical origins of the act of promising itself? Was it necessary for the first rudimentary promises to be made, that individuals were capable of objective reasoning? To fully understand and answer this question, we must first note a necessary pre-requisite for promises to be made, namely the ability of individuals to make normative choices concerning potential action. For one to be capable of reasoning on procedures for purposes more or less taken for granted… that they serve the subject’s interest in relation to self-preservation – be that of the single individual, or of the community on whose maintenance that of the individual depends. The idea that an aim can be reasonable for its own sake – on the basis that virtue and insight reveals it to have in itself – without some kind of subjective gain or advantage, is utterly alien to subjective reason…” Max Horkheimer, Eclipse of Reason (London: Continuum Publishing Company, 1974) p.3 5 Korsgaard, Self Constitution p.191 6 Ibid p.192 2 Copyright Sam Hurcom motivations for and against keeping a promise, one must be capable of normatively evaluating one’s choices. The historical context in which the first promises were made will be closely linked with the emergence of normative deliberation. If our ability to make normative choices emerged through objective reasoning i.e. our ability to recognise certain reasons to act as transcending personal goals and desires, then arguably our ability to make promises (and furthermore our ability to recognise moral laws as motivation for action) was also a consequence of objectively reasoning. This is the view Korsgaard attempts to defend throughout Self-Constitution (primarily from chapter six onwards); she initially begins by presenting a genealogy of sorts, outlining the origins of normativity. To begin, Korsgaard notes that the distinction between human action and the actions of animals concerns the “…interaction of two factors, an incentive and a principle. The incentive is a motivationally loaded representation of an object… The principle determines, or we may say describes, what the animal does, or tries to do, in the face of an incentive”7. The incentives of a tiger may present certain animals (objects) as things to be eaten; the governing principles of the tiger determine what will be done in light of the incentive, namely ‘catch and eat the object’. In the case of non-human animals, the principles that govern action in light of incentives are comprised solely by instinct. Such instincts can be understood as self-governing laws, in so much as they arise from an animal’s physical design and abilities; the instincts of a hummingbird will greatly differ from that of a tiger therefore. Nevertheless, both the hummingbird and tiger’s actions will be governed by instinct in the light of certain incentives; at the sound of a gunshot the actions of the hummingbird and tiger may greatly differ but the actions of both will have been purely instinctive. In this 7 Korsgaard, Self-Constitution, p.109 3 Copyright Sam Hurcom sense the animals “…instincts are the laws of [their] own causality, they are in effect the animal’s will”8 For an animal to have a well formed instinctive response is for said animal to conceptualise the world in light of its own subjective identity i.e. needs and desires. The most primitive creature will have normative instinctive responses, that is a set of requirements that are good or bad in light of the actions required for the animals maintained survival, but ”…the animal knows nothing of the normative; she doesn’t need to, because it is built right into the way she perceives the world”9. In other words, though an animal may have certain primitive reasons to act in light of certain incentives, which she can succeed or fail to fulfil, such reasons only exist in light of the animal’s subjective organisation of her perceived world. In light of Korsgaard’s aim of presenting the origins of normative evaluation requisite for actions such as promising and moral choice, she argues that in instances where an animal’s will is composed of her instincts, there exists no evaluative ‘space’ (no evaluative capability) between the incentive for action and the principle governed response. Korsgaard notes that such a claim could fall in line with a classic distinction made between instinctive and intelligent action; an intelligent response is one governed by an evaluation of possible choices, whereas an instinctive response is a natural automated reaction. In response to this claim however, Korsgaard also argues that this distinction is far too over simplified and crude in light of the fact that many animals exhibit action that requires some degree of intelligence. 8 9 Korsgaard, Self-Constitution, p.110 Ibid. p.113 4 Copyright Sam Hurcom Intelligent animals are capable of learning from experience and forming causal connections between certain objects or primitive concepts (an intelligent animal may have a primitive understanding of gravity by making the causal connection between an object and its falling from a certain height to the ground). “So intelligence is a capacity to forge new connections, to increase your stock of automatically appropriate responses. Intelligence so understood is not something contrary to instinct, but rather something that increases its range…”10 In this sense, an intelligent animal is capable of making choices concerning the satisfaction of certain instinctive needs. If, from experience, a tiger understands the he has caught more prey at the river than on the plateau, he can greater enhance his chances of satisfying his need for food by hunting down by the river. Intelligence allows for an increase in the options of instinctive responses available to the tiger concerning his incentives and instinctive will. Intelligence can further stretch to instrumental thinking, where an understanding of an object’s properties through experience can lead to said objects use as a rudimentary tool. In this sense, “…the world of tools and obstacles presented by instinct is elaborated and changed in ways that contribute to the animal’s flexibility in dealing with changes in her environment…”11 Even in instances of extreme intelligence resulting in instrumental thinking however, the actions of an animal (intelligently deliberated or not) extend only to the satisfaction of the instinctive will of the creature i.e. the principle from which all action is motivated remains the animal’s instincts. In terms of means and ends discussion, we could suggest that the actions of an animal are solely concerned with the fulfilment of certain means (avoiding other predators, catching prey) for the satisfaction of instinctive ends 10 11 Korsgaard, Self-Constitution, p.113 Ibid. p.114 5 Copyright Sam Hurcom (survival, feeding). The distinguishing feature of animals and rational human agents therefore will lie in our ability to make choices that are not motivated from (or in some instances contrary to), our natural instincts. As human agents, we can deliberate on the principles that govern our actions in response to certain incentives, thereby freeing our will from purely instinctive drives. The concern of this essay lies with Korsgaard’s understanding of how rational human agents are made aware of what she calls ‘the potential grounds for action’, and the following claim that this awareness “…of the workings of the grounds of our beliefs and actions gives us control over the influence of those grounds themselves”12 Korsgaard’s claim, is that an awareness of the principle that governs our action in the face of incentive opens up “… a space of what I call reflective distance”13. This reflective space results in the liberation from instinct, as it provides an evaluative realm where one’s incentives can be judged as potential reasons to act. Whilst instinct still exists as a principle providing possible responsive actions, it is not our sole principle from which possible actions can be realised. The imposition of rational principles can provide further choices of responsive actions, thereby allowing an agent to make a choice between ends. Rather than only being tasked with choosing the mere means of satisfying a principle, an agent is now capable of choosing whether to abide to the principle itself. Whilst instinct may cause the potential action of fleeing from the battlefield, rational principles concerning moral virtue may provide us with reasons to fight and possibly commit an act of self-sacrifice. Korsgaard notes that the reflective space that emerges through an awareness of the potential grounds for action is the development of a particular form of self-consciousness 12 13 Korsgaard, Self-Constitution, p.116 Ibid. p.116 6 Copyright Sam Hurcom and that such self-consciousness is specific to rational human agents and no other animals. But in terms of genealogical history how can such a form of self-consciousness emerge? This is arguably a key concern (perhaps criticism) of Korsgaard’s thesis. Korsgaard fails to adequately explain how any intelligent animal, endowed with instrumental thinking of the highest order, naturally progresses to a self-conscious awareness of the constitutive principle that governs its action, without any external influence on its behaviour? In other words, how could such an awareness of the potential grounds for action emerge in primitive homo-sapiens and not in other animal species such as chimps (or even tigers)? Furthermore, why does a mere awareness of one’s governing constitutive principle give one a reason to act against it? Arguably, Korsgaard is not implying that an awareness of one’s governing principle provides any substantial reason or motivation to act against it. What creature, whose instinctive will had maintained its survival since birth, would choose to act against such instinct freely, simply by becoming aware that such instinct governed its actions? But how then can Korsgaard explain humankind’s ability to act on principles distinct from mere instinctive willing in modernity? What key steps are missing from her thesis that take humanity from a mere awareness of constitutive principles for action to acting against our natural, instinctive principles altogether? Whilst we can accept that Korsgaard provides thorough accounts of what distinguishes human agents from animals and further what distinguishes reason from mere intelligence, she fails to account for how such distinctions emerge in any genealogical sense. Korsgaard’s failure to adequately present the context in which an awareness of the potential grounds for action (the emergence of normative choice) emerged is extremely significant to her conclusive argument in chapter nine that actions such as promises, stem 7 Copyright Sam Hurcom solely from an objective form of reasoning. As normative evaluation is a pre-requisite of promise making, and Korsgaard argues all promise making is instantiated by objective reasoning, we need a clear explanation of how the emergence of normative choice was facilitated through objective reasoning. In other words, failure to demonstrate that objective rationality resulted in the emergence of normative choice, which in turn is a prerequisite for promise making, could suggest, that certain normative choices can be made on purely subjective grounds. This would imply that there could be cases in which promises were made and kept for wholly subjective (private) reasons. If it can be demonstrated that the earliest normative choices and subsequent promises were made for purely subjective reasons, then Korsgaard’s concrete claim in chapter nine, that all promises require deliberation of individual’s concerning their public reasons, would appear false. An understanding of what initially caused both an awareness of the potential grounds for action, as well as the motivation to act on reasons contrary to instinct may be found in Nietzsche’s Genealogy on Mordality14 (primarily the second essay ‘”Guilt”, “Bad Conscience” and Related Matters’) One of Nietzsche’s fundamental goals is to establish a social/historical context in which the most primitive customs of moral law emerged. Furthermore, Nietzsche attempts to establish under what circumstances, primitive human beings developed the rational principles of reflection that suppressed their instinctive wills. Nietzsche’s discussion is highly significant to this essay as it provides greater insight into the context under which normativity emerged in humankind, as well as discussing the consequential emergence of, the self-conscious individual, moral language (good/bad, good/evil) and actions necessary for social organisation and function such as promising. 14 Friedrich Nietzsche, ‘On the Genealogy of Morality: A Polemic (2 nd Essay)’ in The Nietzsche Reader (ed.) K.A. Pearson & D. Large (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2006) pp.408-424 8 Copyright Sam Hurcom Nietzsche begins his second essay by addressing the pre requisite features, necessary for human beings to be capable of making promises15. The act of promising is arguably of grave necessity for the functioning and success of any social structure, and key to the act itself are the concepts of contractual obligation and duty. Within the act of promising lies (among other things), the rational faculties of causality and its relation to time, the ability to anticipate, calculate as well as remember. But prior to the development of these faculties, Nietzsche suggests “…the more immediate task of first making man to a certain degree undeviating, uniform, a peer amongst peers, orderly and consequently predictable.”16 In the pre-historical period Nietzsche coins ‘the Morality of Custom’ the intense “labour of man on himself”17 in which the uniformity of human beings occurs stretches, “the longest epoch of the human race.”18 Predictability or regulation in this sense is concerned with the curbing and controlling of human beings instinctive will, inclinations and desires. For the most basic and fundamental social organisations to exist, a degree of regulation must be demonstrated by its inhabitants. In a historical context, primitive human beings were once endowed with a purely instinctive will like all other intelligent animals. For Nietzsche, the ‘Morality of Custom’ is the expanse of time in which (in Korsgaard’s terminology) an awareness of the potential grounds for action would emerge. It is in this time that human beings rational principles would have emerged to make contractual agreements and the regulation of instinctive action possible. For Nietzsche, this regulation and ability to curb instinctive 16 Nietzsche, ‘On the Genealogy of Morality…’ p.409 Ibid. p.409 18 Ibid. p.409 17 9 Copyright Sam Hurcom drives is justification for the barbaric and violent methods demonstrated throughout the age. Nietzsche argues that the ability to remember (necessary for contractual social agreements such as promising) or to“…give a memory to the animal, man…”19 lies in the “oldest (and unfortunately longest- lived) psychology on Earth”20. To be endowed with the ability to remember is to learn from experience that forgetfulness will lead to pain, suffering and torment. The brutality of punishment witnessed in the morality of custom held a purpose; to inspire fear and dread into those who failed to keep their word and fulfil their contractual promises. Arguably the barbaric nature of punishment was imposed on all instances where individuals acted against the norms and customs of the society in the interests of their instinctive will. Through the imposition of cruel social punitive measures, individuals were taught or governed to supress their instinctive will and reflect upon their instinctive incentives. “With the aid of this sort of memory, people finally came to ‘reason’! – Ah, reason, solemnity, mastering of emotions, this really dismal thing called reflection, all these privileges and splendours man has: what a price had to be paid for them!21 On this reading, the potential grounds for action emerge in a violent and brutal age, where the instinctive will of individuals was suppressed and regulated for the development of primitive social structures and organisations. More importantly however, it presents a full account of the facts resulting in primitive human beings acting against their instinctive will, something Korsgaard fails to provide in Self-Constitution. Korsgaard argues that a specific form of self-consciousness is required for an awareness of the potential grounds for action 19 Nietzsche, ‘On the Genealogy of Morality…’ p.410 Ibid. p.410 21 Ibid. p.411 20 10 Copyright Sam Hurcom and similarly, Nietzsche argues that specific form of ‘bad conscience’ will emerge through the suppression of instinctive willing. This “serious illness”22 results from the dramatic shift in governing principles of action human beings abide to. Where instinct once provided all necessary responses to incentives and possible choices of action, the “…change whereby he finally found himself imprisoned within the confines of society and peace…”23 resulted in one’s own natural responses being evaluated, scrutinised and ultimately suppressed. Whilst instinct remained to provide possible responses, inclinations and motivations for action, individuals were forcibly made to act against them. Under these circumstances, the individual is truly made aware of the potential grounds for action i.e. made aware that they could potentially act on their instinctive drives. For Nietzsche, the emotion of guilt and the concept of the soul emerge in this “internalization of man”24 , the ‘momentous’ act in which an individual must act against its very own nature. The result of this internalisation of instinctive willing leads to a change in the “…whole character of the world” 25 whereby human beings ceased to exist as merely intelligent animals in the natural world endowed with instinctive wills and instead became regulated and internally conflicted rational agents. If the above discussion is endorsed, it would appear that a more thorough account of the awareness of the potential grounds for action can be supplemented by Nietzsche’s concept of social regulation. We can note, that the first normative choices were not derived from any reflective awareness of objective reasons distinct from individuals purely instinctive willing; the first normative choices were made between possible action derived from one’s own natural instinctive will or the governing force of superior social powers in society. 22 Nietzsche, ‘On the Genealogy of Morality…’ p.419 Ibid. p.419 24 Ibid. p.419 25 Ibid. p.419 23 11 Copyright Sam Hurcom Korsgaard wishes to argue, that there emerged at this time a dichotomy with instinctive willing providing wholly subjective/personal motivations to act on the one hand, and a reflective awareness of reasons distinct from this willing providing objective/public motivations to act on the other. This however would not have been the case in light of Nietzsche’s argument. The first normative choices were made concerning the natural principles of instinct and the rudimentary laws of society.26 Ultimately, individuals were imposed with the choice to act on their instinctive wills, thereby incurring grave punishments, or act in accordance with the rudimentary laws of society, thereby denying one’s instinctive willing. The emergence of normative choice was governed by purely subjective interests; arguably it was a choice concerned with maintenance of one’s own life and survival. This reading would perhaps harmonise better with the genealogical discussions presented by both Korsgaard and Nietzsche; the first normative choices were still, in many respects, animalistic as they were choices concerned with the means to one’s own continued survival. This subjective understanding of primitive, normative choices helps make clear the manner in which the earliest social contracts and promises were made in. As Nietzsche suggests, promises emerge as a social necessity; they ensure organised and stable social functioning. The motivating factor or reason to maintain a promise on this view was wholly subjective; not only was it in the interests of the individual to keep their promise to another (for fear of the punitive measures that could arise from breaking a promise) but it was also in the interests of the wider society that promises were maintained. No awareness of metaphysically superior or objective principles motivates or governs the act of making a 26 As has already been mentioned acting in the interests of one’s society is still an instance of subjective reasoning; one Is still non-directly acting in one’s own interests. 12 Copyright Sam Hurcom promise at this time. Whilst much of the moral language still in use today, as well as the mythology and religious doctrine that cemented moral laws, may have been introduced at this time, arguably it was all a means of reinforcing the dominance and control of leading powers in society, whilst also solidifying the necessity to curb instinctive willing and act in accordance with social laws. One response to the above claim may be to suggest that these early forms of promising are not the true representation of how we perceive the act of promising today; the lack of individual autonomy demonstrates that these promises were by no means a shared deliberation between individuals. As Korsgaard may suggest, this is not a true representation of the type of moral action that requires an awareness of public reasons at all. Simply accepting that the earliest forms of promise were indeed forcibly imposed and regulated however does not imply, that a lack of force or regulation in modernity requires concepts of shared deliberation and public reasons to explain the act of promising. Why can it not be suggested that we make and keep promises for wholly personal/subjective reasons – would this not also explain why we often break our promises; due to a lack of personal motivation to keep them? What we can conclude therefore is that the necessary conditions for promising to occur were in fact motivated from subjective/personal interests, thereby resulting in the earliest promises being made and kept from solely subjective interests and reasoning. 13 Copyright Sam Hurcom Bibliography - Horkheimer, M. Eclipse of Reason (London: Continuum Publishing Company, 1974) - Korsgaard, C. Self-Constitution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012) - Nietzsche, F. ‘On the Genealogy of Morality: A Polemic (2nd Essay)’ in The Nietzsche Reader (ed.) K.A. Pearson & D. Large (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2006) pp.408-424 14