Lecture 9 of Book II George Eliot

advertisement

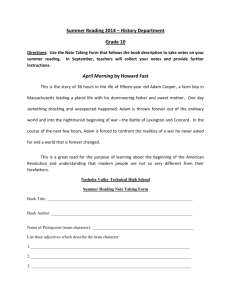

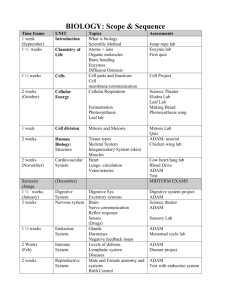

Lecture 9 of Book II George Eliot Brief Introduction George Eliot (1819-1880), the pseudonym of Mary Ann Evans. She was born in the family of a land agent, and spent her childhood amid the rural scenery of Warwickshire in the Midlands. She did a great deal of reading and learned music and “the German, French and Italian languages.' She had been brought up under strict religious influences, but she early abandoned religious beliefs, became a freethinker, and showed a great interest in social and philosophical problems. she became acquainted with the Italian revolutionary Mazzini (1805-t872) and George Henry Lewes, a well-known philosopher and critic, with whom she entered into a union, without legal form, which lasted until his death in 1878. Major Works She translated into English Feuerbach's "The Essence of Christianity‘. In 1857, she wrote her first three stories for a magazine, which were later published in book form under the title "Scenes of Clerical Life.' "Adam Bede" (1859); " The Mill on the Floss' (1860) and "Silas Marner' (1861). These works, describing rural life, dealt with moral problems and contained psychological studies of character. In 1863, Eliot published "Romola', a historical novel of the Renaissance in Italy, also discussing problems of religion and morality. In 1866 appeared her "Felix Holt the Radical", a novel on political questions. " Middlemarch" (1871-1872) and "Daniel Deronda" (1876) were Eliot's last novels. Introduction of Major Works (1) Adam Bede It is a study of the impact of Methodism on English country life. It is known for its pastoral beauty, a high moral tone as well as psychological study of characters. Adam Bede is a young carpenter respected by everyone as a good workman and an honest and uptight man. He is in love with pretty Hetty Sorrell. However, she cares nothing for him and is interested in Captain Donnithorne. Meanwhile, Adam's brother Seth has fallen in love with a young Methodist preacher, Dinah Morris. Also niece of Mrs. Poyser, Dinah is unlike her cousin Hetty as Adam is unlike his brother Seth. Hetty is a pretty, helpless kitten, but Dinah is of firm and serious mind. Adam proposes to Hetty and is gladly accepted by Mr. And Mrs. Poyser, but Hetty leaves home alone before the wedding. She is now pregnant with Captain Donnithorne's child. She wanders around looking for him and the child is born on the way. She leaves the baby to die in a wood and is imprisoned, sentenced to deportation and dies a few years later on her way home. Gradually Dinah and Adam are drawn towards each other. The story ends with the union of them two. The detailed physical realism here is matched up by a studied psychological realism which, focusing on the inner being of a character, derives from details about the thoughts and the emotions of characters: their personalities, their motives, their feelings about themselves, each other, and their surroundings. Her depiction of the "soul struggle"--in which one is torn in conscience between something he knows is morally and ethically right, and something that is tempting and attractive. George Eliot's penetrating insight into the motives, the likes and dislikes, and hesitations of Adam, Donnithorne and Hetty is ample evidence of her grasp of psychological realism. The Mill on the Floss It is essentially autobiographical. Story: Maggie Tulliver is a girl of intellectual distinction, ardent nature, rich imagination, with a strong desire for love and ideal. Because she is tomboyish, dark-skinned, dreamy, and indifferent to the conventional ideas, she finds it almost impossible for her to be accepted by her better-off relatives, however hard she tries. One day, she goes to visit her brother Tom at school, and there she is attracted to Philip Wakem, the disabled but intelligent son of a rival of her family. Despite her brother's forbiddance, she and Philip meet secretly. Two years later, Maggie, now a teacher, goes to visit her cousin, Lucy Dearie. There Maggie and Stephen, her cousin's boyfriend, are attracted to one another at first sight. One day, Stephen and she go boating together and the tide carries them beyond the reach of the shore and they are forced to spend the night in the boat. Her people refuse to listen to her explanation and her brother turns her away from the mill house he has just regained from the Wakems. Between two men who both profess to love her, she feels she owes it to her cousin, not to allow Stephen to fall in love with her, and she feels she owes it to her brother not to marry Philip. Finally, she leaves both men and comes back in a terrible flood to revue her brother. The brother and sister are united and drowned. Comments: Maggie's tragedy lies in the incompatibility between a strong passion and a sense of propriety within herself, and in the incompatibility between the individual ideal and the confining social circumstances. Although she can make better use of the classical schooling than her brother, she has no opportunity to advance in education. So, she must content herself with the narrow place Victorian society allows for girls of her class. Her sense of the call of duty and propriety overrides her own wild emotion and forces her to give up her deep sympathy for Philip and deeper feelings for Stephen. Silas Marner Story Silas Marner, a poor dissenting weaver, is betrayed by his friend and wrongly accused of theft, loses his girlfriend, and goes into exile in a remote country district. For fifteen years he lives a lonely life, living for no purpose but to hoard the money he receives for his weaving. One night, his money is stolen, and he mourns for his gold every day. On New Year's Eve, a poor woman dies in the snow near Marner's house and her little gold-haired baby girl crawls towards Marner's lighted cottage. Returning from an errand, Silas finds the sleeping baby, mistaking it for his lost gold. He turns all his love for the baby girl and brings her up. With its arrival, he is brought back into human fellowship and happiness. Comments Silas Marner is a moral tale, a story of redemption. Its message is clear to modern readers: true wealth is love, not gold. As a myth of loss and redemption, the novel concerns the miser Silas Marner, who loses his material riches only to reclaim a greater treasure of contentment. Silas comes to learn that happiness is possible only for the pure and self sacrificing. Because of his love for the orphan girl, he is transformed, as if by magic, from a narrow, selfish, bitter recluse into a truly human, spiritually fulfilled man. The book is also noted for the great poetic beauty and compactness of structure. Middlemareh, a Study of Provincial Life In this novel, George Eliot sets out to paint what she describes as "a life of mistakes, the offspring of a certain spiritual grandeur ill matched with the meanness of opportunity". Here, she is investigating human aspirations, in particular, the aspirations of those extraordinary people to serve and do good to others and society. It is made up of two parts: one is the fight for fulfillment by the individual human being, with his frailties, imperfect self-knowledge and weak willpower, and the other is the limitation of the society. Confined to Middlemareh, both Dorothea and Lydgate, starting with more than ordinary promise, have to rest content with very ordinary achievement; both, seeking something beyond the provincial life, have finally to subject themselves to the limitations of the reality. But while our anger is directed at the limited social environment, we nonetheless feel that their own mistakes and weakness in character are also to blame. As the subtitle suggests, the novel is "a study of provincial life" in the 19th-century England. In the study of the lives of Dorothea and Lydgate, the determining force of the whole provincial town of Middlemarch is highlighted. At the same time, George Eliot pays much attention to the psychological study of the mind and inner feelings of the characters, and with constant comment and analysis, leads the reader, step by step, to the inevitable ending. Psychological study of human nature (1) She was a pioneer to the modern psychoanalytical novel, the first to "put all actions inside". (2) Her interest is not merely in the depiction of people and their life, but in the discovery and analysis of some fundamental truth about human life. (3) In her works, she seeks to present the inner struggle of an individual and to reveal the motives, impulses and hereditary influences that govern human actions. (4) By placing the responsibility for a man's life firmly on the moral choices of the individual, she changes the nature of English novel: character becomes plot. (5) By emphasizing the moral choices of the individual, she makes character develop in their own logical way. (6) Moreover, George Eliot believes that the truth about human life can only be found in the inner struggle of the character and mutual reaction between the individual and the society he lives in. (7) It is George Eliot who first joins the two worlds, i.e. the inward propensity of individual and the outward social circumstances, and show them both working on the lives of individuals. Her determinism (1) Individuals are shaped by a number of determining forces: the force of environment or nature, the force of heredity, the force of education, and the force of human conventions. (2) These forces of human and natural, moral and animal, civilized and primitive are all interwoven and interconnected in determining the fate of an individual. (3) If one suffers or fails, he himself is as much to blame as the society. As a matter of fact, individual failure, as influenced and determined by the combined forces of both individual and society, does make up a constant theme in her fiction. (4) She sees tragedy as part of human life. Her tragedy is not inevitably death, but in most cases expressed as failure of individual ideals. Book Four of Adam Bede Chapter XXVII A crisis IT was beyond the middle of August--nearly three weeks after the birthday feast. The reaping of the wheat had begun in our north midland county of Loamshire, but the harvest was likely still to be retarded by the heavy rains, which were causing inundations and much damage throughout the country. From this last trouble the Broxton and Hayslope farmers, on their pleasant uplands and in their brook-watered valleys, had not suffered, and as I cannot pretend that they were such exceptional farmers as to love the general good better than their own, you will infer that they were not in very low spirits about the rapid rise in the price of bread, so long as there was hope of gathering in their own corn undamaged; and occasional days of sunshine and drying winds flattered this hope. The eighteenth of August was one of these days when the sunshine looked brighter in all eyes for the gloom that went before. Grand masses of cloud were hurried across the blue, and the great round hills behind the Chase seemed alive with their flying shadows; the sun was hidden for a moment, and then shone out warm again like a recovered joy; the leaves, still green, were tossed off the hedgerow trees by the wind; around the farmhouses there was a sound of clapping doors; the apples fell in the orchards; and the stray horses on the green sides of the lanes and on the common had their manes blown about their faces. And yet the wind seemed only part of the general gladness because the sun was shining. A merry day for the children, who ran and shouted to see if they could top the wind with their voices; and the grown-up people too were in good spirits, inclined to believe in yet finer days, when the wind had fallen. If only the corn were not ripe enough to be blown out of the husk and scattered as untimely seed! And yet a day on which a blighting sorrow may fall upon a man. For if it be true that Nature at certain moments seems charged with a presentiment of one individual lot must it not also be true that she seems unmindful uncon-scious of another? For there is no hour that has not its births of gladness and despair, no morning brightness that does not bring new sickness to desolation as well as new forces to genius and love. There are so many of us, and our lots are so different, what wonder that Nature's mood is often in harsh contrast with the great crisis of our lives? We are children of a large family, and must learn, as such children do, not to expect that our hurts will be made much of--to be content with little nurture and caressing, and help each other the more. It was a busy day with Adam, who of late had done almost double work, for he was continuing to act as foreman for Jonathan Burge, until some satisfactory person could be found to supply his place, and Jonathan was slow to find that person. But he had done the extra work cheerfully, for his hopes were buoyant again about Hetty. Every time she had seen him since the birthday, she had seemed to make an effort to behave all the more kindly to him, that she might make him understand she had forgiven his silence and coldness during the dance. He had never mentioned the locket to her again; too happy that she smiled at him--still happier because he observed in her a more subdued air, something that he interpreted as the growth of womanly tenderness and seriousness. "Ah!" he thought, again and again, "she's only seventeen; she'll be thoughtful enough after a while. And her aunt allays says how clever she is at the work. She'll make a wife as Mother'll have no occasion to grumble at, after all." To be sure, he had only seen her at home twice since the birthday; for one Sunday, when he was intending to go from church to the Hall Farm, Hetty had joined the party of upper servants from the Chase and had gone home with them--almost as if she were inclined to encourage Mr. Craig. "She's takin' too much likin' to them folks i' the house keeper's room," Mrs. Poyser remarked. "For my part, I was never overfond o' gentle folks's servants--they're mostly like the fine ladies' fat dogs, nayther good for barking nor butcher's meat, but on'y for show." And another evening she was gone to Treddleston to buy some things; though, to his great surprise, as he was returning home, he saw her at a distance getting over a stile quite out of the Treddleston road. But, when he hastened to her, she was very kind, and asked him to go in again when he had taken her to the yard gate. She had gone a little farther into the fields after coming from Treddleston because she didn't want to go in, she said: it was so nice to be out of doors, and her aunt always made such a fuss about it if she wanted to go out. "Oh, do come in with me!" she said, as he was going to shake hands with her at the gate, and he could not resist that. So he went in, and Mrs. Poyser was contented with only a slight remark on Hetty's being later than was expected; while Hetty, who had looked out of spirits when he met her, smiled and talked and waited on them all with unusual promptitude. That was the last time he had seen her; but he meant to make leisure for going to the Farm tomorrow. To-day, he knew, was her day for going to the Chase to sew with the lady's maid, so he would get as much work done as possible this evening, that the next might be clear. One piece of work that Adam was superintending was some slight repairs at the Chase Farm, which had been hitherto occupied by Satchell, as bailiff, but which it was now rumoured that the old squire was going to let to a smart man in top-boots, who had been seen to ride over it one day. Nothing but the desire to get a tenant could account for the squire's undertaking repairs, though the Saturday-evening party at Mr. Casson's agreed over their pipes that no man in his senses would take the Chase Farm unless there was a bit more ploughland laid to it. However that might be, the repairs were ordered to be executed with all dispatch, and Adam, acting for Mr. Burge, was carrying out the order with his usual energy. But to-day, having been occupied elsewhere, he had not been able to arrive at the Chase Farm till late in the afternoon, and he then discovered that some old roofing, which he had calculated on preserving, had given way. There was clearly no good to be done with this part of the building without pulling it all down, and Adam immediately saw in his mind a plan for building it up again, so as to make the most convenient of cow-sheds and calf-pens, with a hovel for implements; and all without any great expense for materials. So, when the workmen were gone, he sat down, took out his pocketbook, and busied himself with sketching a plan, and making a specification of the expenses that he might show it to Burge the next morning, and set him on persuading the squire to consent. To "make a good job" of anything, however small, was always a pleasure to Adam, and he sat on a block, with his book resting on a planing-table, whistling low every now and then and turning his head on one side with a just perceptible smile of gratification--of pride, too, for if Adam loved a bit of good work, he loved also to think, "I did it!" And I believe the only people who are free from that weakness are those who have no work to call their own. It was nearly seven before he had finished and put on his jacket again; and on giving a last look round, he observed that Seth, who had been working here to-day, had left his basket of tools behind him. "Why, th' lad's forgot his tools," thought Adam, "and he's got to work up at the shop tomorrow. There never was such a chap for wool-gathering; he'd leave his head behind him, if it was loose. However, it's lucky I've seen 'em; I'll carry 'em home. The buildings of the Chase Farm lay at one extremity of the Chase, at about ten minutes' walking distance from the Abbey. Adam had come thither on his pony, intending to ride to the stables and put up his nag on his way home. At the stables he encountered Mr. Craig, who had come to look at the captain's new horse, on which he was to ride away the day after to-morrow; and Mr. Craig detained him to tell how all the servants were to collect at the gate of the courtyard to wish the young squire luck as he rode out; so that by the time Adam had got into the Chase, and was striding along with the basket of tools over his shoulder, the sun was on the point of setting, and was sending level crimson rays among the great trunks of the old oaks, and touching every bare patch of ground with a transient glory that made it look like a jewel dropt upon the grass. The wind had fallen now, and there was only enough breeze to stir the delicate-stemmed leaves. Anyone who had been sitting in the house all day would have been glad to walk now; but Adam had been quite enough in the open air to wish to shorten his way home, and he bethought himself that he might do so by striking across the Chase and going through the Grove, where he had never been for years. He hurried on across the Chase, stalking along the narrow paths between the fern, with Gyp at his heels, not lingering to watch the magnificent changes of the light--hardly once thinking of it--yet feeling its presence in a certain calm happy awe which mingled itself with his busy working-day thoughts. How could he help feeling it? The very deer felt it, and were more timid. Presently Adam's thoughts recurred to what Mr. Craig had said about Arthur Donnithorne, and pictured his going away, and the changes that might take place before he came back; then they travelled back affectionately over the old scenes of boyish companionship, and dwelt on Arthur's good qualities, which Adam had a pride in, as we all have in the virtues of the superior who honours us. A nature like Adam's, with a great need of love and reverence in it, depends for so much of its happiness on what it can believe and feel about others! And he had no ideal world of dead heroes; he knew little of the life of men in the past; he must find the beings to whom he could cling with loving admiration among those who came within speech of him. These pleasant thoughts about Arthur brought a milder expression than usual into his keen rough face: perhaps they were the reason why, when he opened the old green gate leading into the Grove, he paused to pat Gyp and say a kind word to him. He remained as motionless as a statue, and turned almost as pale. The two figures were standing opposite to each other, with clasped hands about to part; and while they were bending to kiss, Gyp, who had been running among the brushwood, came out, caught sight of them, and gave a sharp bark. They separated with a start—one hurried through the gate out of the Grove, and the other, turning round, walked slowly, with a sort of saunter, towards Adam who still stood transfixed and pale, clutching tighter the stick with which he held the basket of tools over his shoulder, and looking at the approaching figure with eyes in which amazement was fast turning to fierceness. After that pause, he strode on again along the broad winding path through the Grove. What grand beeches! Adam delighted in a fine tree of all things; as the fisherman's sight is keenest on the sea, so Adam's perceptions were more at home with trees than with other objects. He kept them in his memory, as a painter does, with all the flecks and knots in their bark, all the curves and angles of their boughs, and had often calculated the height and contents of a trunk to a nicety, as he stood looking at it. No wonder that, not-withstanding his desire to get on, he could not help pausing to look at a curious large beech which he had seen standing before him at a turning in the road, and convince himself that it was not two trees wedded together, but only one. For the rest of his life he remembered that moment when he was calmly examining the beech, as a man remembers his last glimpse of the home where his youth was passed, before the road turned, and he saw it no more. The beech stood at the last turning before the Grove ended in an archway of boughs that let in the eastern light; and as Adam stepped away from the tree to continue his walk, his eyes fell on two figures about twenty yards before him. "I don't know what you mean by flirting," said Adam, "but if you mean behaving to a woman as if you loved her, and yet not loving her all the while, I say that's not th' action of an honest man, and what isn't honest does come t' harm. I'm not a fool, and you're not a fool, and you know better than what you're saying. You know it couldn't be made public as you've behaved to Hetty as y' have done without her losing her character and bringing shame and trouble on her and her relations. What if you meant nothing by your kissing and your presents? Other folks won't believe as you've meant nothing; and don't tell me about her not deceiving herself. I tell you as you've filled her mind so with the thought of you as it'll mayhap poison her life, and she'll never love another man as 'ud make her a good husband." "Well, Adam," said Arthur, "you've been looking at the fine old beeches, eh? They're not to be come near by the hatchet, though; this is a sacred grove. I overtook pretty little Hetty Sorrel as I was coming to my den--the Hermitage, there. She ought not to come home this way so late. So I took care of her to the gate, and asked for a kiss for my pains. But I must get back now, for this road is confoundedly damp. Good-night, Adam. I shall see you to-morrow--to say good-bye, you know." Arthur was too much preoccupied with the part he was playing himself to be thoroughly aware of the expression in Adam's face. He did not look directly at Adam, but glanced carelessly round at the trees and then lifted up one foot to look at the sole of his boot. He cared to say no more--he had thrown quite dust enough into honest Adam's eyes-and as he spoke the last words, he walked on. "Stop a bit, sir," said Adam, in a hard peremptory voice, without turning round. "I've got a word to say to you." Arthur paused in surprise. Susceptible persons are more affected by a change of tone than by unexpected words, and Arthur had the susceptibility of a nature at once affectionate and vain. He was still more surprised when he saw that Adam had not moved, but stood with his back to him, as if summoning him to return. What did he mean? He was going to make a serious business of this affair. Arthur felt his temper rising. A patronising disposition always has its meaner side, and in the confusion of his irritation and alarm there entered the feeling that a man to whom he had shown so much favour as to Adam was not in a position to criticize his conduct. And yet he was dominated, as one who feels himself in the wrong always is, by the man whose good opinion he cares for. In spite of pride and temper, there was as much deprecation as anger in his voice when he said, "What do you mean, Adam?" "I mean, sir"--answered Adam, in the same harsh voice, still without turning round--"I mean, sir, that you don't deceive me by your light words. This is not the first time you've met Hetty Sorrel in this grove, and this is not the first time you've kissed her." Arthur felt a startled uncertainty how far Adam was speaking from knowledge, and how far from mere inference. And this uncertainty, which prevented him from contriving a prudent answer, heightened his irritation. He said, in a high sharp tone, "Well, sir, what then?" "Why, then, instead of acting like th' upright, honourable man we've all believed you to be, you've been acting the part of a selfish light-minded scoundrel. You know as well as I do what it's to lead to when a gentleman like you kisses and makes love to a young woman like Hetty, and gives her presents as she's frightened for other folks to see. And I say it again, you're acting the part of a selfish light-minded scoundrel though it cuts me to th' heart to say so, and I'd rather ha' lost my right hand." "Let me tell you, Adam," said Arthur, bridling his growing anger and trying to recur to his careless tone, "you're not only devilishly impertinent, but you're talking nonsense. Every pretty girl is not such a fool as you, to suppose that when a gentleman admires her beauty and pays her a little attention, he must mean something particular. Every man likes to flirt with a pretty girl, and every pretty girl likes to be flirted with. The wider the distance between them, the less harm there is, for then she's not likely to deceive herself." "I don't know what you mean by flirting," said Adam, "but if you mean behaving to a woman as if you loved her, and yet not loving her all the while, I say that's not th' action of an honest man, and what isn't honest does come t' harm. I'm not a fool, and you're not a fool, and you know better than what you're saying. You know it couldn't be made public as you've behaved to Hetty as y' have done without her losing her character and bringing shame and trouble on her and her relations. What if you meant nothing by your kissing and your presents? Other folks won't believe as you've meant nothing; and don't tell me about her not deceiving herself. I tell you as you've filled her mind so with the thought of you as it'll mayhap poison her life, and she'll never love another man as 'ud make her a good husband." Arthur had felt a sudden relief while Adam was speaking; he perceived that Adam had no positive knowledge of the past, and that there was no irrevocable damage done by this evening's unfortunate rencontre. Adam could still be deceived. The candid Arthur had brought himself into a position in which successful lying was his only hope. The hope allayed his anger a little. "Well, Adam," he said, in a tone of friendly concession, "you're perhaps right. Perhaps I've gone a little too far in taking notice of the pretty little thing and stealing a kiss now and then. You're such a grave, steady fellow, you don't understand the temptation to such trifling. I'm sure I wouldn't bring any trouble or annoyance on her and the good Poysers on any account if I could help it. But I think you look a little too seriously at it. You know I'm going away immediately, so I shan't make any more mistakes of the kind. But let us say good-night"—Arthur here turned round to walk on--"and talk no more about the matter. The whole thing will soon be forgotten." "No, by God!" Adam burst out with rage that could be controlled no longer, throwing down the basket of tools and striding forward till he was right in front of Arthur. All his jealousy and sense of personal injury, which he had been hitherto trying to keep under, had leaped up and mastered him. What man of us, in the first moments of a sharp agony, could ever feel that the fellowman who has been the medium of inflicting it did not mean to hurt us? In our instinctive rebellion against pain, we are children again, and demand an active will to wreak our vengeance on. Adam at this moment could only feel that he had been robbed of Hetty-- robbed treacherously by the man in whom he had trusted--and he stood close in front of Arthur, with fierce eyes glaring at him, with pale lips and clenched hands, the hard tones in which he had hitherto been constraining himself to express no more than a just indignation giving way to a deep agitated voice that seemed to shake him as he spoke. "No, it'll not be soon forgot, as you've come in between her and me, when she might ha' loved me--it'll not soon be forgot as you've robbed me o' my happiness, while I thought you was my best friend, and a noble-minded man, as I was proud to work for. And you've been kissing her, and meaning nothing, have you? And I never kissed her i' my life--but I'd ha' worked hard for years for the right to kiss her. And you make light of it. You think little o' doing what may damage other folks, so as you get your bit o' trifling, as means nothing. I throw back your favours, for you're not the man I took you for. I'll never count you my friend any more. I'd rather you'd act as my enemy, and fight me where I stand--it's all th' amends you can make me." Poor Adam, possessed by rage that could find no other vent, began to throw off his coat and his cap, too blind with passion to notice the change that had taken place in Arthur while he was speaking. Arthur's lips were now as pale as Adam's; his heart was beating violently. The discovery that Adam loved Hetty was a shock which made him for the moment see himself in the light of Adam's indignation, and regard Adam's suffering as not merely a consequence, but an element of his error. The words of hatred and contempt--the first he had ever heard in his life--seemed like scorching missiles that were making ineffaceable scars on him. All screening self-excuse, which rarely falls quite away while others respect us, forsook him for an instant, and he stood face to face with the first great irrevocable evil he had ever committed. He was only twenty-one, and three months ago--nay, much later--he had thought proudly that no man should ever be able to reproach him justly. His first impulse, if there had been time for it, would perhaps have been to utter words of propitiation; but Adam had no sooner thrown off his coat and cap than he became aware that Arthur was standing pale and motionless, with his hands still thrust in his waistcoat pockets. "What!" he said, "won't you fight me like a man? You know I won't strike you while you stand so." "Go away, Adam," said Arthur, "I don't want to fight you." "No," said Adam, bitterly; "you don't want to fight me--you think I'm a common man, as you can injure without answering for it." "I never meant to injure you," said Arthur, with returning anger. "I didn't know you loved her." "But you've made her love you," said Adam. "You're a double-faced man--I'll never believe a word you say again." "Go away, I tell you," said Arthur, angrily, "or we shall both repent." "No," said Adam, with a convulsed voice, "I swear I won't go away without fighting you. Do you want provoking any more? I tell you you're a coward and a scoundrel, and I despise you." The colour had all rushed back to Arthur's face; in a moment his right hand was clenched, and dealt a blow like lightning, which sent Adam staggering backward. His blood was as thoroughly up as Adam's now, and the two men, forgetting the emotions that had gone before, fought with the instinctive fierceness of panthers in the deepening twilight darkened by the trees. The delicate-handed gentleman was a match for the workman in everything but strength, and Arthur's skill enabled him to protract the struggle for some long moments. But between unarmed men the battle is to the strong, where the strong is no blunderer, and Arthur must sink under a well-planted blow of Adam's as a steel rod is broken by an iron bar. The blow soon came, and Arthur fell, his head lying concealed in a tuft of fern, so that Adam could only discern his darkly clad body. He stood still in the dim light waiting for Arthur to rise. The blow had been given now, towards which he had been straining all the force of nerve and muscle--and what was the good of it? What had he done by fighting? Only satisfied his own passion, only wreaked his own vengeance. He had not rescued Hetty, nor changed the past--there it was, just as it had been, and he sickened at the vanity of his own rage. But why did not Arthur rise? He was perfectly motionless, and the time seemed long to Adam. Good God! had the blow been too much for him? Adam shuddered at the thought of his own strength, as with the oncoming of this dread he knelt down by Arthur's side and lifted his head from among the fern. There was no sign of life: the eyes and teeth were set. The horror that rushed over Adam completely mastered him, and forced upon him its own belief. He could feel nothing but that death was in Arthur's face, and that he was helpless before it. He made not a single movement, but knelt like an image of despair gazing at an image of death. Arthur seduces Hetty and then deserts her. The broken-hearted girl consents then to marry Adam, but presently discovers that she is pregnant. She flees from her village. In the course of events she is bought to court and charged with the murder of her child. The following chapters describe the trial of Hetty Sorrel and her ultimate fate Themes Inner vs. Outer Beauty Eliot contrasts inner and outer beauty throughout the novel to express the idea that external and internal realities do not always correspond. Although Hetty is more physically beautiful than Dinah, she is cold and ugly inside. Hetty’s outer beauty masks her inner ugliness, especially to Captain Donnithorne and Adam. Even when Hetty cries or is angry, she still appears lovely to both men. Adam is so blinded by Hetty’s appearance that he often misinterprets her tears and excitement as love for him. Hetty’s outer beauty also blinds Captain Donnithorne such that he loses control when she cries and he kisses her. Unlike Hetty, Dinah has an inner beauty because she helps and cares for those around her. She comforts Lisbeth through the mourning of her dead husband, and Adam takes notice of this. Adam does not think Dinah is as physically beautiful as Hetty, but he is drawn to her love and mission to help those around her. His feelings for Dinah change after he witnesses Dinah consoling Hetty, and Adam begins to see Dinah as outwardly beautiful. Eliot’s description of the natural beauty of the English countryside also shows the contrast between internal and external beauty. On the day Hetty wanders off to find Captain Donnithorne, the day is beautiful and the countryside is magnificent. However, Hetty suffers enormously under the weight of her plight. Eliot uses this contrast to encourage the reader to look beyond the surface and explore a deeper meaning. The Value of Hard Work One of the chief differences between the good characters and the evil characters is their commitment to working hard. Most of the characters in Adam Bede are hard-working peasants who spend their days laboring on farms, in mills, or in shops. Those characters are generally characterized by gentle intelligence and simple habits. They do their best not to harm others, and they produce goods others can use and value. Examples are Mrs. Poyser, whose dairy supplies the other villagers and whose cream cheese is renowned in the area; Adam, whose skills in carpentry are unmatched and who is a good and fair manager of people and resources; and Dinah, who works in a mill. By contrast, those few malingerers in the novel are generally evil as well as lazy. The strongest example of laziness is Captain Donnithorne, who often complains that he has nothing to do, and whose boredom may well have contributed significantly to Hetty’s downfall. If Captain Donnithorne had been busy sowing fields, he might not have engaged in his illicit and unwise affair. Those who work hard take pride in their work, and they do not harm others because they are careful and meticulous and do not have time for idle self-indulgence. Love as a Transformative Force Love has the power to transform characters in the novel. The characters who love are portrayed as gentle, kind, and accepting. Dinah, for example, is a preacher but is never preachy. She accepts Hetty as she is, even when Hetty is peevish and selfish toward her. Dinah’s love transforms Hetty in jail because she comforts and listens to Hetty and does not judge her. Before, Hetty was selfish and only thought about her own happiness. After, she is sincerely sorry for the shame she caused her family and even apologizes to Adam. Another example is Mrs. Poyser, and how she can be harsh toward those she loves. When Hetty’s crime comes to light, Mrs. Poyser is the only one in her family who does not seem to judge Hetty. Here, Mrs. Poyser transforms from strict and critical to a loving and accepting woman. The one character that is not transformed by love is Mrs. Irwine, who is critical and sharp and never manages to help others. She does not feel, and so she is neither transformed by love nor capable of transforming others. For example, at Captain Donnithorne’s coming-of-age party, one of her presents to a peasant girl is an ugly gown and a piece of flannel. This gift only aggravates the girl and makes her reject the present. Mrs. Irwine thinks she is giving the girls only what they deserve, and therefore she is not transformed by love because she does not care for anyone. Love only transforms the characters that want to help people other than themselves. The Consequences of Bad Behavior Bad behavior and wrongdoing have consequences that extend beyond the wrong-doer, and even relatively small transgressions can have massive collateral effects. The central lesson from Hetty’s experience with Captain Donnithorne is that doing the right thing is important because doing the wrong thing might hurt others in ways that cannot be controlled. Though Captain Donnithorne is not inherently evil, he provokes bad behavior in Hetty because she cannot go to him for help when she learns that she is pregnant. Hetty is ashamed and only thinks of herself when she commits her crime. As she awaits the trial, Hetty does not think about how her bad behavior affected anyone else: she does not consider the shame she has caused the Poysers or the effect her crime has on Adam. Hetty feels no real remorse for her sins and just wishes to not be reminded of any wrong she has done. Eventually, she apologizes to Adam and asks God for forgiveness, but the lesson of the story is that bad behavior, evil, and wrongdoing cannot be undone. Motifs Natural Beauty Eliot’s description of the natural beauty of the English countryside, especially in scenes of great sadness or evil, expresses the idea that external and internal realities do not always correspond. For example, when Hetty wanders off toward Windsor to find Captain Donnithorne, the day is beautiful and the countryside is magnificent. The reader would think Hetty’s stunning looks combined with the sunny countryside backdrop would describe an equally joyful scene in the book. However, unbeknownst to the reader, Hetty suffers enormously under the weight of her plight. Although Hetty herself is beautiful, her appearance contrasts with her internal character, which is weak, selfish, and ugly. Unlike Dinah, who is beautiful both externally and internally, Hetty has no inner beauty. Eliot uses the contrast between internal and external beauty to encourage the reader to look beyond the surface of people and things to their deeper characteristics and meanings. Dogs The dogs in the novel reflect the temperament of the characters with respect to helpless beings. Adam’s dog, Gyp, loves his master. He is happy and trusting and devoted to Adam. Gyp’s condition reflects Adam’s love of the helpless and his desire to help and care for those who depend on him. Mr. Massey’s dog is also healthy but cowers whenever Mr. Massey displays his split personality. As one who deeply cares for the helpless, Mr. Massey can be grouchy and crotchety even while he provides nourishment and assistance to those in need. Mr. Irwine has dogs, who are happy and contented. They laze around the hearth. As his relationship with his dogs suggests, Mr. Irwine is kind and gentle toward those who depend on him, but he is a little lazy and cares more for the comforts of his home. Narrative Sarcasm The narrator in Adam Bede butts into the story to provide ironic and often sarcastic commentary on the characters and the reader’s impression of them. The narrator pokes fun at the reader, especially the imagined, haughty reader who has a low opinion of such simple characters as Adam and Mr. Irwine. Making fun of the reader has two effects. First, it feeds the idea that the nobility is frivolous and a bad judge of character. The narrator clearly approves of the characters, and the narrator calls into question the reader’s judgment by suggesting that the reader does not. Second, the satire keeps the narrative brisk and the tone light. The narrator pushes the heavy idea that readers should not judge others and that they should love their neighbors. To avoid becoming preachy, the narrator uses humor, and a big part of that humor is in the sarcasm. Symbols Gates The characters in the novel frequently linger around gates and pass through gates outside homes and in the fields. The gates suggest major changes in the characters’ lives, as when Hetty passes through the gates as she walks toward the Chase to meet Captain Donnithorne, leaving the innocence of childhood behind and walking into a very adult situation. The gates outside the characters’ homes also represent the attempt to keep the affairs of the heart private. Those who are allowed to pass through those gates are allowed into the heart of the family and into its most intimate secrets. Adam does not create any disturbance when he comes through the gates at Hall Farm: he is an accepted and beloved member of the community, and he enters quietly and respectfully. In contrast, Captain Donnithorne creates a huge ruckus whenever he enters. He loudly calls to Dinah at one point, and at other points he arrogantly makes his presence known. Adam comes quietly into the Poysers’ confidence while Captain Donnithorne brings noise, disturbances, and, ultimately, shame. Hearth and Home The hearth and home are the sources of nourishment in the novel, and their images recur repeatedly as the grounding force of the characters’ lives. The most prominent example of hearth and home is Hall Farm, the home of the Poysers. Each of the scenes at the farm returns to the hearth, where the grandfather sits and around which the whole family gathers. Problems are discussed and conflicts are resolved around the hearth. In the same way, at the Bedes’ home, life revolves around the hearth in the kitchen. Lisbeth’s whole day is spent there, and Dinah is useful and praised when she visits because of her ability to clean, cook, and do chores near the fireplace. The strongest and most worthwhile characters are those who spend the most time around the hearth. Clothing The characters’ choice of clothing represents important qualities of their nature, showing on the outside how they choose to represent themselves to the world. Hetty, for example, dresses in the best finery she can get, whereas Dinah dresses all in black with a simple cap. Hetty’s ostentatious dress symbolizes the shallow, flashy nature of her character, and when her dress falls into disrepair on her trip, it tracks the disintegration of her spirit. By contrast, Dinah’s black gown and simple dress symbolize her practical love of simple things. She chooses not to put herself forward but to shrink into the background and come forward only when she can help others. Characters’ clothing choices reflect fundamental truths about their natures. Key Facts genre · Bildungsroman; tragedy time and place written · 1857–1859, England narrator · The narrator is an anonymous historian who knows Adam later in life. The narrator has a low opinion of the reader, whom he imagines as a socialite woman. point of view · The narrator speaks primarily in the third person, centering on characters one at a time and revealing their thoughts and feelings in turn. Sometimes, the narrator breaks through to comment on the actions and feelings of the character in the first person. tone · The narrator is generally empathetic with the characters, although sometimes the narrator is very sarcastic about the reader’s imagined response to the characters. tense · Past tense setting (time) · June 1799–June 1807 setting (place) · Hayslope, England protagonist · Adam Bede major conflict · Adam Bede comes to terms with the disgrace and crimes of his fiancée and learns how evil acts in the world. rising action · When Hetty Sorrel has an affair with Captain Donnithorne, gets pregnant, and murders her newborn child, Adam Bede must face the reality that not all people conform to his conception of goodness. climax · Adam’s discovery of Hetty’s crime forces upon him the knowledge of her pregnancy and the death of her child; for him, life will forever be marked by the sorrow he feels over her disgrace. falling action · Adam observes Hetty’s trial from afar, forgives Hetty, and returns to life in Hayslope. Only over time is he able to come to terms with Hetty’s disgrace and exile from England. themes · The value of hard work; the power of love; the consequences of bad behavior motifs · Natural beauty; dogs; narrative sarcasm symbols · Gates; hearth and home; clothing foreshadowing · Adam hears the omen of death the night before his father dies; Hetty’s impending shame is her pregnancy; Dinah blushes when Adam surprises her at the Bede home, foreshadowing their love and marriage. Questions 1. Why does Eliot title her novel Adam Bede? What is the book really about? Adam Bede is about Adam Bede. Though Adam actually is not part of the central actions of the novel, the novel is not driven by its plot. Instead, the novel focuses on the characters of Hayslope and how they react when a tragedy occurs in their midst. Adam is the central figure of the novel because he is a good man who undergoes a significant personality change in the face of great sorrow. Eliot begins the novel by showing us Adam in ordinary life. He is a carpenter and a hard worker, but he is too proud of his work. Adam supports his family, but he is too hard on his wayward father. The death of his father causes Adam to reflect on his own character, but this sadness is not enough to bring about a complete personality change. The events with Hetty, however, cause Adam to completely reconsider his view of the world. They change him by making him gentler, humbler, and, on the whole, a better man. Eliot intends us to model ourselves in some small part on Adam. An admirable character, Adam is meant to guide readers through their own lives. The novel is a moral novel. It is meant to show how even so admired and brave and good a man as Adam is in the beginning of the story can be made better by a little compassion toward his fellow man. The narrator often emphasizes this point when he breaks through the story to make comments. That is why Eliot calls the book Adam Bede. She intends to keep the focus on him, even through the more exciting plot developments that center on other characters. 2. Eliot claimed that the scene of Hetty’s conversion of the jail was the point toward which the whole novel was driving. Do you agree? Dinah’s prayer with Hetty in jail and Hetty’s ultimate conversion are a major emotional highpoint in the novel, but they are not the climax of the book. Although Hetty is at the center of all the major action of the novel, she is not the subject of the story. Instead the story focuses on Adam and Dinah. To the extent that Dinah preaches to Hetty and the reader sees Dinah as a preacher and religious woman, the scene is important for what it says about Dinah. It is also a critical scene because it shows the effects of compassion in action. Where no one else could touch Hetty’s hard heart, Dinah can through her gentleness and lack of judgment. The scene embodies the moral of the novel, that judging our neighbors is not a proper way to live and that love has more transformative power than all the preaching in the world. For that reason, the scene is at the heart of the novel’s emotional power. It crystallizes Eliot’s moral purpose in writing the novel and renders clear the meaning that is threaded through the rest of the story. But because Hetty and even Dinah are really secondary to Adam in their place in the novel, the scene between them in the jail is not the climax. This scene inspired the novel, but the novel grew away from it in the telling. Adam’s life is the more complex and more elaborated allegorical version of the message encapsulated in the jail scene, and his life is the focus of the book. 3. Why is Adam so blind to Hetty’s true nature? Adam cannot see Hetty’s faults because he wants so badly for her to be the perfect wife for him and because she is so beautiful. Adam falls victim to Hetty’s charms because he believes the best of everyone. He sees the world in good terms and expects others to see it that way too. Because he loves Hetty, in his love he believes what he wants to believe about her: that she is innocent, caring, and gentle. Adam also expects inner beauty to correlate to outer beauty. But Adam is a practical man, and to him, building a strong, straight wall is doing God’s work. A wall seldom has characteristics that are much hidden from the human eye, and Adam expects people to be like walls, basically self-revealing of flaws and cracks. But people, of course, are not like that. Although Hetty’s strength does not derive from good, she is strong in her own way, and her powers of deception are exceptional. Adam expects her to be the kitten she seems. Whether his infatuation and blindness lessen his character is something Eliot leaves to her reader to decide. She argues that his infatuation stems from his finest qualities. Adam’s inability to see the truth, however, does set him up for misery. Had they married, Hetty and Adam would likely have been an unhappy couple. Suggested Essay Topics 1. How is the role of women in society portrayed in the novel? What significance, if any, do you think it has on the novel that George Eliot is a woman who took on a male pseudonym? 2. Why is it important that Dinah Morris and Seth Bede are Methodists? Is Adam Bede a religious novel? 3. Is Captain Donnithorne responsible for Hetty’s plight? Is he a bad man? 4. Why is Dinah the only person able to get through to Hetty while she is in jail? 5. Why is Adam so devastated by Hetty’s crime and incarceration? What does the reaction of the different characters to the news about Hetty say about them?