Spirituality In Medicine and Health Care

advertisement

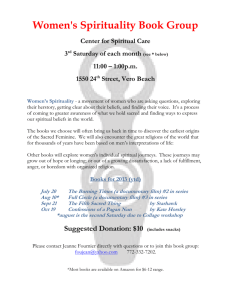

Spirituality In Medicine and Health Care Dr. Thomas R. McCormick Dept. of Medical History & Ethics U.W. School of Medicine Adjunct Professor: Bioethics Program, Midwestern University University of Washington MHE, Family Med, Soc Wk, Pastoral Care MHE 518 & Fam Med 547 “Spirituality in Health Care” A QUESTION OF “MEANING MAKING” The Golden Temple Kyoto, Japan 2/3/05 Buddhist Tradition • Brahma-Net Sutra: “Sons of Buddha, when you see all the ill persons, you should offer them exactly the same as you offer the Buddha with no difference.” • 2500 year tradition. Shinto Shrine Osaka, Japan 02/04/05 In Every Culture We Find Evidence of the Search for Meaning • • • • Why am I here? What should I do with my life? How do I order my priorities? Where can I find guidance about the “good life” or the “life well lived?” When faced with sickness or the threat of dying. . . WHERE DO I NOW FIND MEANING? • In the face of loss? • Is it temporary or permanent? • Mourning the loss of the “former self” • The unknown of a different self. • An uncertain future? These Are Questions of Meaning • Questions of meaning and purpose are often described as “spiritual issues.” • These questions are part of being human, they transcend culture, religion, ethnicity, they are universal. Boston Marathon Consider the case of Dax Cowart • Dax excelled in football, was a rodeo rider, & a jet fighter pilot in Viet Nam; Burned over 65% of his body; • Blind; • Facially disfigured; • Loss of most fingers; WHAT KIND OF FUTURE? Dax Insisted: “Please Let Me Die” • Early in burn rehab---should we allow him to forego treatment? • If he survives to mid-stage treatment and then wants to die, should we stop treatment? • If he is nearly finished with treatment, discharge is on the horizon, but without completing treatment he would become infected and die. . . Should we stop? • How is it some want to live, others to die? Health Care is a Partnership • So far we have focused on the patient, his values, questions of “best interest.” • What about the health care provider? Our sense of meaning, our values, may be challenged by the patient. “Complaint” William Carlos Williams • They call me and I go, It is a frozen road past midnight, a dust of snow caught in the rigid wheeltracks. The door opens. I smile and enter and shake off the cold, Here is a great woman on her side in the bed, She is sick, perhaps vomiting, perhaps laboring. Today’s Topic: Spirituality in Health Care • There are many advances in the biomedical sciences that create new & difficult choices for patients and their families from the cradle to the grave. • The topic of spirituality addresses values and beliefs that patient’s bring to the table about whether or not to avail themselves of these medical advances. Spirituality, which pertains to ultimate meaning and purpose in life, has clinical relevance. • Many patients find spiritual support in coping with illness and recovery. • For patients experiencing suffering and facing death, spirituality provides a context that offers meaning, purpose and hope. • There is a remarkable resurgence of interest in spirituality in the United States and in its relationship to well being and abundant life. The divergence between medicine and spirituality • Modern medicine has developed marvelous advances and interventions, relying more on diagnostic procedures and less on patients’ conversations. • Managed care, by limiting the time spent with each patient, makes it more difficult to discover the patient’s spiritual concerns and most deeply held goals and values. How did we get here? • To appreciate the current divergence between modern medicine and the role of spirituality in health care, we need to remember our history. Health Care in Early Times Medicine & Religion • Few interventions were possible • Application of herbal medicines • Religious concepts of cause and effect included : – – – – punishment for sins indwelling of evil spirits separation of the patient from God or the unknowable mystery of illness Ancient medicine & religion • 3000 BCE, early written documents show Egyptian & Mesopotamian healers were priests with magico-religious concepts. • 5th century BCE in Greek medicine, Hippocrates begins a more scientific approach, including natural causes. • By the 3rd century BCE, the Romans were influenced by the Greek’s cult of Asclepius. Greece: The Temple of Asclepius Two views of health care HYGEIA & ASCLEPIUS • HYGEIA: health is the natural order of things, fostered by prudent choices and wise living, the goal is to find balance between a sound body, a sane mind, and a calm spirit-medicine should discover & teach the natural laws, so we might cooperate. • ASCLEPIUS: the chief role of medicine is to treat disease, the heroic intervenor. Nursing care and natural healing processes grow from the approach of Hygeia. Interventive Medicine has its roots in Aesclepius Medicine in the Christian era • Healings were attributed to Jesus, who sometimes linked healing with the power to forgive sins. • The Parable of the Good Samaritan became a formative influence on medicine. • By the 5th century AD, virtually all physicians were drawn from clergy in the monastic communities. (Kuhn, Psychiatric Medicine Vol. 6 No. 2) Medical historians claim that the story also had a profound affect upon the practice of medicine. For centuries, physicians were recruited and trained in the monasteries, which were repositories of medical texts which were preserved and copied by the monks. The physician’s duty was to care for the patient, without regard for race, religion, gender or any other feature, other than the patient’s need. Secular Medicine • Secular medicine emerged in the late middle ages, but was still under control of church. • 1140 AD church granted first medical licenses, conditions, & revocations. • 1789, the French Revolution, marked the break down of religious control over medicine. • Cartesian: separation of mind and body Separation of Medicine from Religion • As science began to discover the etiology of diseases, former religious explanations no longer held. • Science and medicine began to distance themselves from religion & God of the gaps (in knowledge). Theoretical Models Emerge • Biomedical model in the 19th century • Psychobiological model--after Freud – emotional states contribute to illness – relaxation response may reverse illness • 20th century: bio-psycho-social model – 1977, George Engel – Life events & lifestyles affect health A Current view of health care: A BIO-PSHYO-SOC-SPIRITUAL MODEL • • • • Scientific view of pathophysiology Respect for the psychological Perception of the social environment Attention to the spiritual distress and the spiritual resources of the patient • Described by Division of Behavioral Medicine at the University of Louisville School of Medicine The Spiritual Definitions: • The patient is not just body and mind, but a spiritual being. --P. Tournier • Spirituality involves the personal quest for meaning & purpose in life and relates to the inner essence of the self • Spirituality: the sense of harmonious interconnectedness with self, others, nature and an Ultimate Other (the integrating factor) Bio-Psycho-Social-Spiritual • Although Schools of Medicine have been slower to recognize & appropriate this model, Social Work has utilized this. • The Nursing Profession has long recognized the spiritual aspects of patient care, • Chaplains and clergy have often assisted patients with the spiritual aspects of illness and the search for meaning & purpose. Religion is seen by some to be an impediment to medicine • Jehovah’s Witness who refuses a life saving blood transfusion; plight of the minor child. • Christian Scientist who refuses allopathic health care in favor of a Reader; • Various religions that may decry contraception when it appears to be medically indicated. • Polarization about abortion decisions or stem cell research. Great Diversity of Religions • Especially in the USA, there is a great number of religions so that one can hardly speak of religion in general, without making reference to a particular religion. • It is too much to expect of a hcp that s/he be a student of religions, in addition to medicine. • And, what if the hcp is non-religious? Question: Should health care professionals avoid talking about religion or spirituality with patients? • A. yes, because one can not be expected to be conversant with all religions; • B. yes, because the hcp may be an atheist or non-believer; • C. yes, because that might be an unethical intrusion into the privacy of the patient; • D. no, particularly when there are indications of patient interest. . . Distinction: Between Religion and Spirituality • Answer: D, no, there are indications (the Bible on the table, the crucifix, other signs. . .) • A particular religion or faith community is one road to spiritual awareness and growth. • Spirituality in this sense, transcends a particular religion, and resides in that universal human space where individuals seek to understand the meaning & purpose of their lives, and what they most value. • Spirituality implies self-conscious living. Many Manifestations “I Am Awake” (Aware) A surgeon’s visit to the bedside on the eve of surgery. . . • Dr. Lester Savauge, cardiothoracic surgeon at Providence Medical Center, described his practice of visiting patients the evening before their surgery in my ethics class, UW. • He felt convinced that this “human touch” contributed to the recovery of his patients. • He sometimes asked, “what would you like to do with the days that will be added onto your life?” Spirituality • Thousands of alcoholic patients who found little help from traditional medicine were able to become sober and remain abstinent by relying on “a power greater than themselves” and through the support of a twelve step program. • Many may not adhere to a religious institution, but have a spiritual practice. A Shift of focus: from the biomedical to the psycho-social-spiritual • For many patients facing the end of life, the focus shifts from the biomedical to the spiritual. • When symptom management and pain control are appropriately provided, patients are set free to address their “final agenda.” • This may be seen as the last chapter in one’s spiritual journey. (Mary Levine) R.M. Mack, MD “Occasional notes: Lessons learned from living with cancer.” NEJM 311:1642, 1984 • “Simply accepting this prognosis was completely intolerable for me. I felt I was not yet ready to be finished. I still had not seen and done and shared with the people I love. . . I could sit back and let my disease and my treatment take their course, or I could pause and look at my life and ask, What are my priorities? Dr. Mack,continuing. . . • How do I want to spend the time that is left? I began to focus on choosing to do things every day that promote laughter, joy, and satisfaction. . . I began to make choices to do the things that felt good to me.” • One person, opening to the meaning of life in the face of imminent death. . . What do patients nearing the end of life say? • • • • • fear of uncontrolled pain & neg. symptoms worry about becoming a burden on family concern about financial costs of care uncertainty about the dying process anxious anticipation of surrendering the known for the unknown • Concern for the “unfinished business of life” Patients in Rehab Medicine face issues of Loss • Case of a university student with a spinal injury from a skiing accident, leaving him paraplegic---committed suicide in the earliest stages of stabilization and rehab. • Conversely, many quadriplegic patients choose to live in the face of even greater losses of function and independence (Christopher Reeves) Patients raise spiritual questions • Who am I, now that I am sick or dying? • What is the meaning of my life when I am no longer productive and independent? • Where am I connected to others who value me and see me as a person of worth? • What is my relationship to the Ultimate? • What do I now value most in the time that is left to me? Am I ready to die? Epictetus: a question of meaning • “It is not as important what happens to a person, as to the meaning that the person gives to what has happened.” • Assignment of meaning is a spiritual function. Lipowski: how we view illness • • • • • • • Illness a challenge Illness as enemy Illness as punishment Illness as weakness Illness as relief Illness as strategy Illness as having value Where does spirituality fit? • Patients may have coping mechanisms related to their belief • May be supported by a community of caring others. • May feel themselves to be in the company of the Divine. Well designed studies are revealing a beneficial relation • Religious commitment, practices and attitudes are related to: • Patient well-being, stress reduction, recovery from illness, reduction of depression, substance abuse prevention and recovery, prevention of heart disease and high blood pressure, mitigation of pain, & adjustment to disability. (Annals of Internal Medicine Vol. 132.No.7 4 April 2000) Focus on human hope. . . Emerging Data: • U.Michigan study of 108 women with gynecological cancer: 93% indicated their religious lives helped them sustain hopes. • American Cancer Society study found 85% of women with breast cancer indicated religion helped them cope with illness. • Sloan-Kettering study found religious beliefs of patients provided a helpful active cognitive framework in dealing with illness. Studies of 203 patients in Kentucky and North Carolina. . . • 77% wanted physicians to consider their spiritual needs; • 37% wanted physicians to discuss these needs more frequently; • 48% wanted their physicians to pray with them if they could; • 68% said their physicians never discussed religious beliefs with them at all. • 74% felt spirituality to be important. Association of American Medical Colleges • “Physicians must seek to understand the meaning of the patients’ stories in the contexts of the patients’ beliefs, and family and cultural values. They must avoid being judgmental when the patients beliefs and values conflict with their own.” Different cultures may have ceremonies and rituals of special importance in coping with illness or preparing for death. Taking a spiritual history. . . (Todd Maugans, MD) • • • • • • S Spiritual Belief System P Personal Spirituality I Integration in a Spiritual Community R Ritualized Practices and Restrictions I Implications for Health Care T Terminal Events Planning (advance directives, DNR wishes, DPOA etc..) HOPE Model • • • • H O P E Sources of hope, meaning, comfort Organized religion Personal spiritual practices effects on medical care and EOL issues Recent surveys by NIHR find: (National Institute for Health Research) • 43% of physicians pray for their patients, • 90% of doctors at the American Academy of Family Physicians 1996 meeting agreed that “a patient’s spiritual beliefs can be helpful in his or her medical treatment” • 58% have actively pursued information on spirituality and healing. American Psychiatric Association • Physicians should maintain respect for their patient’s beliefs. It is useful for physicians to obtain information on the religious or ideologic orientation and beliefs of their patients. . . • Physicians should not impose their own religious, antireligious, or ideologic systems of belief on their patients. . . Doctors, and patient stories. . . • Doctor’s duty, to provide a diagnosis, a pathophysiological plot explaining signs and symptoms. • Doctor’s reward, to behold the life journey of patients and apprehend their meanings.