Copyright© 2008 Read more or contact Bierdz at: http://bierdz.org

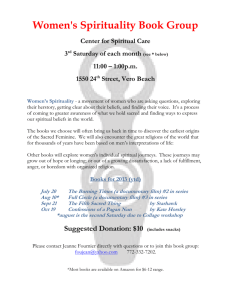

advertisement

Currently there is a bit of contention in the West when it comes to the terms, “religious” and “spiritual.” Recent studies on how these terms are perceived show that, in general, the terms are used interchangeably, but when people are pressed on the matter the term “religious” is viewed as being more rigid and dogmatic than “spiritual,” which is seen as more holistic and open. When given the choice between being classified as religious or spiritual, people tend to prefer the latter, as they find it less restricting. Thus, one can self-identify as being spiritual without being religious. Interestingly, the history of religious writings reflects this idea, as it is replete with examples of those who are religiously robust, while being spiritually dead. But what do these terms actually mean, and how can learning their meaning help us move forward in life? In about 100 BCE, a Roman statesman named Cicero created a Latin philosophic vocabulary. He traced the term, Religion, to the root word, religari, which means “to read over again.” Soon after this others traced the word to ligare- meaning “to bind together” (as found in the word ligament.) Even though the origins of the term are unclear, the underlying idea of strictness is evident: as reading something “over again” certainly does “bind” one to the text. To work all of the world’s religions into a single definition that does justice to each is a daunting, and perhaps an impossible, task. This is because fitting all of the various nuances and subtleties of even two religions into a phrase that one can neatly slip into their pocket is like capturing all of the various and unique characteristics of an elephant and a fish in a few short paragraphs. (Give it a try and you will soon understand why it has not been successfully done to date). However, this function of “to bind together” is at the core of most all definitions of religion. Spirituality is another term with uncertain roots; however it is generally agreed that it comes from spiritus, which is related to spirare, “to breath; the breath.” In its earliest traceable use, about 100 CE. a spiritual person was one who was oriented to God. By the 12th century, the term was connected to one’s psychological virtue apart from worldly goods. In the 18th and 19th century, its use died but was later resurrected in the 20th century by French Catholic writers with its original meaning intact. Today its Copyright© 2008 meaning is more connected to human potential and striving: The Human Spirit. The term’s current incarnation may partly be due to a resurgence of the ancient, pantheistic view that states: “Because God is in all things; we can therefore realize our divine nature and recognize that we are God.” Here, the orientation is still to God, but the focus is on the internal God: not the external. Hence, we can place a person’s conceptualization of spirituality into one of three groups: Exotheistic: one being oriented to the external God in the hope of becoming more aligned with God’s will; Pantheistic: realizing that one is God, and; Humanistic, recognizing one’s potential for selfimprovement apart from any particular belief in God. Although we lack a practical universal definition that can capture all religions, the fact that religion is universal has been well established. What should be noted is that all religions, from Adventists to Zoroastrianism, are traceable to a founder. Each founder had an “experience” that he or she shared with others: breathing new life into them. Soon, the “way to the experience” was modified and expanded and became standardized over time. Whenever a person wanted to share in the experience, they were then bound to “the way.” When latter followers of the founder had their own experiences that differed from the religion, they established their way to which their followers were bound. And thus, one religion broke into many, with each claiming the true connection to the founder. With this understanding, we can see that spirituality can precede religion, can be reciprocally linked to it, or can stand alone. (Of course there are many other factors involved in the establishment and propitiation of a religion, but the general idea here is sufficient for our purposes of understanding the process). Knowing that a spiritual experience can happen apart from religion, become the foundation of a religion, or come out of religious traditions, can help us grow and improve our lives. This knowledge can help us understand our own faith traditions, be more open to accepting the religious and spiritual practices of others, and increase our level of comfort, exploring new practices as we continue in our own spiritual development. Read more or contact Bierdz at: http://bierdz.org/